By : Chris Russell

The people in the packed room listen intently as the speaker spells out the virtues of adaptability, creativity and his own personal refusal to box himself in with a job title on his business card. Those standing at the back of the room crane their necks to hear his words. The last of eight speakers drawn from tech companies and venture capital firms, at the end of his talk members of the crowd begin conversing with one another over bottles of beer, tech buzzwords dominating.

It sounds like a scene from Silicon Valley, but instead the event, hosted by start-up incubator Chinaccelerator, took place in the newly opened shared office space of People Squared in Shanghai's Jing'an district, its third such space in the city.

In China's drive to transform itself into an economy centered on innovation, these grassroots scenes full of eager, ambitious start-ups will play a crucial role.

Such is the government's desire to foster technological innovation that the Politburo, China's top decision making body, took the unusual and significant step of holding a study session in September in Beijing's Zhongguancun, an area routinely hailed as "China's Silicon Valley". "We must enhance awareness of unexpected challenges and grab the opportunity of the science and technology revolution. We cannot wait, hesitate or slack," Xi Jinping, China's President, said.

For all that urgency, just how close is any one place in China to claiming the mantle of Silicon Valley, a place that represents the confluence of money, talent, entrepreneurship and an unwavering belief that any problem can be solved through technology'

More than One

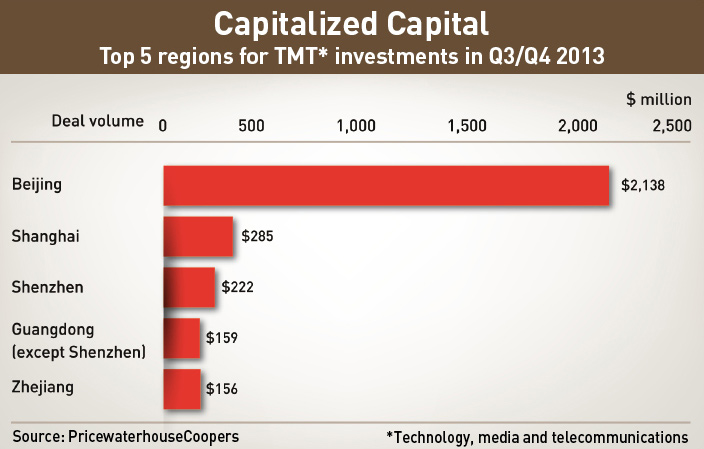

Unlike in the US, where tech innovation is largely clustered in California, the picture in China is much more fragmented, leading to the existence of several candidates for the appellation "China's Silicon Valley". Nonetheless, a few key locations stand out.

"If I had to name the three key areas for innovation, I would say Beijing, Shenzhen and Hangzhou," says Anna Fang, General Manager of ZhenFund, a Beijing-based seed fund.

It is Beijing, and specifically Zhongguangcun, that is perhaps most similar to Silicon Valley. Initially an electronics street, in the 1980s Zhongguancun developed into a nascent tech hub, before later becoming the subject of government policy designed to foster innovation. It became China's first high-tech park in 1988. In that year, the park had 527 enterprises, according to the Zhongguancun Science Park, as the park is now known. By 2012, it was home to just under 15,000 companies, down from a peak of 21,000 in 2007.

Today, among these thousands of companies are giants such as Baidu and Lenovo, and Beijing's broader ecosystem is supported by a plethora of research institutes, multinationals, angel funds and incubators like former Google China CEO Kai-Fu Lee's Innovation Works. The two elite universities nearby, Peking and Tsinghua, have also played a role that in some ways mirrors that of Stanford's to Silicon Valley.

"I would definitely say Beijing really far outpaces Shanghai and Shenzhen, in terms of the number of entrepreneurs, number of investors, number of events," says Rui Ma, the Greater China Investment Partner for 500 Startups, a venture capital seed fund and start-up accelerator. "Beijing is really up there [in Asia] in terms of innovation and activity."

An example of Beijing's status as a leading hub for tech start-ups is the dating app Momo, which allows users to communicate with nearby strangers using their phones. Founded in 2011, the company claims to have reached 120 million registered users in 2014. Meanwhile Momentcam, a photo app that allows users to turn people into comic-like drawings, has attracted Series A funding from Alibaba. Then there is Xiaomi, the newly dominant smartphone brand on everyone's lips.

But if Beijing leads the way on deals and activity, then it is the southern city of Shenzhen, itself the base for tech giants such as Tencent, that has the edge when it comes to hardware, a fact connected to its position in the manufacturing hub of the Pearl River Delta. It is home to a burgeoning group of so-called "makers" (DIY manufacturers and entrepreneurs) who have been drawn to the city due to its access to parts and manufacturing knowhow. In April 2014, Shenzhen hosted its first major Maker Faire, a gathering of makers, engineers, students and business people that originated in the US and has since spread around the world.

"The ecosystem in Shenzhen provides makers with advantages in aspects such as sourcing, manufacturing and logistics, making hardware start-ups scale easier," says Eric Pan, the founder and CEO of Seeed Studio, a Shenzhen-based hardware innovation platform. "Ordering electronics here is now like service in a restaurant."

Shenzhen's unique access to parts and manufacturers greatly reduces production timelines, allowing for greater experimentation. Such endeavors are then bolstered by the likes of Pan's 'hacker space' Chaihuo and Haxlr8r, an accelerator exclusively for companies working with hardware.

The experimentation and innovation evident in Shenzhen has its roots in the city's vast electronics malls, which provide access to a mind-boggling array of parts, and also the region's shanzhai (counterfeit) culture. Although intellectual property (IP) theft has been the bane of many companies manufacturing in China, shanzhai nonetheless inculcated knowledge and flexibility due to the way information was freely shared. This, when combined with the region's advanced manufacturing infrastructure, has given entrepreneurs huge flexibility to operate at many different scales.

Following a well-worn path of moving from follower to leader, companies in Shenzhen now stand to bring the lessons of shanzhai into the arena of innovative and legitimate business, fusing the entrepreneurial spirit of a Silicon Valley start-up with the knowledge and workcraft of Shenzhen manufacturing, allowing for a high degree of experimentation.

An example is DJI. Its drones, or quadcopters, are at the premium end of the market and have found a following around the world. Another is OnePlus which has taken advantage of Shenzhen's unique position to produce what Time magazine described as the "Phone of Dreams", all the while selling it at an ultra-competitive price point.

Shenzhen has strengths in other areas beyond hardware. "Because Tencent is there, they also have great gaming companies and great social networking companies. I mean, Shenzhen is really stellar," says Fang. In 2014, Shenzhen became a national innovation zone, the fourth one in the country and the only zone created on a city-wide scale.

The cities of Shanghai and Hangzhou also lay a claim to being tech hubs, albeit not on the same scale or with the same vitality as Beijing and Shenzhen. Hangzhou benefits from the presence of e-commerce giant Alibaba, while Shanghai boasts tech parks, top universities, the hacker space XinCheJian and Chinaccelerator.

A huge number of national high-tech zones are also spread across the country and are intended to artificially create tech clusters. According to the Torch Program, a government tech entrepreneurship scheme, by 2012 there were 105 such zones. Unlike the DIY hacker spaces of Shenzhen however, these zones are dedicated to serious, high-level research and development—in the case of the Xi'an Hi-tech Industries Development Zone this has attracted major firms such as Huawei, Siemens and IBM.

Driving the development of these tech hubs around the country has been the growth in the overall ecosystem—the networks of venture capital firms, incubators and shared working spaces. According to the Torch Program, in 1995 the number of tech incubators was a mere 73. By 2012, that number had grown to over 1,200.

Similarly, the volume of venture capital funding has increased significantly since the late 1990s, more than doubling between 1998 and 2004 according to an OECD report, with the emergence of university-backed venture capital firms in 2000 being a significant milestone. However, since 2011 numbers have shown a decline, largely because China's initial public offerings (IPO) market was closed for 14 months from October 2012 to December 2013—in 2013, the total amount of invested capital was $3.5 billion according to Ernst & Young, down from $5 billion in 2012.

The Hand of Government

For all the importance of grassroots entrepreneurship and experimentation, the Chinese government plays an important role in tech innovation. The primary vehicle for this has been the Ministry of Science and Technology's Torch Program, which has provided funding, created innovation clusters, established incubators and supported venture capital firms.

Smaller, more localized schemes also exist, such as the Inno Way "innovation street" in Zhongguancun, which offers space and assistance with business services, including faster company registration; the Shanghai Technology Entrepreneurship Foundation for Graduates and the Phoenix Project of Beijing's Chaoyang district. This last scheme, which aims to attract overseas talent, saw its subsidies for start-ups in 2014 doubled to RMB 100,000.

According to Rui Ma, these initiatives are not the primary driving force for innovation, but nonetheless make a beneficial contribution.

"The things they do that make it easier for businesses to get started or easier for early-stage investors to take a little bit more risk are really helpful. We're big supporters of government initiatives that invest in funds, invest in private capital and let the private capital money managers then disperse the capital," she says.

As with any government programs, bureaucracy and myopia remain problems, and the schemes often focus largely on high-tech to the exclusion of other areas of innovation. According to Anil Gupta, Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at the University of Maryland's Robert H. Smith School of Business, research and development (R&D) funds aren't always distributed based on scientific merit. Relationships playing an important role, and there is also a focus on quantity rather than quality.

"We're far less enamored with government initiatives that try to disperse funds themselves, because after all it is a very different industry," says Ma. "There are a lot of government initiatives where [the] government will clear a street or create a finance park—I don't think those are as helpful. They take a really long time to trickle down because generally those are not the resources that entrepreneurs need. Generally what they need is smart capital… just providing space, we haven't seen it really work anywhere in the world."

More than Money

Although China's tech sector has witnessed success and innovation through Tencent's wildly popular WeChat application, which has also begun to gain some traction globally, and with smaller companies, these success stories are still far from the level of Silicon Valley. But there is still plenty of money finding its way to Chinese tech companies, and Fang describes the funding situation for start-ups as "excellent".

"For certain types of businesses, I'm seeing valuations that are actually higher than the US, and the amounts of capital being raised are very comparable," says Ma, although she warns that this situation has led to some talk of a downturn around the corner, with investment activity not always being justified given the fundamentals.

"It's a lot of dumb money, at the end of the day," says Todd Embley, Program Director of Chinaccelerator. "[The investors] can't help them build a business, because they have no idea how to do it themselves."

According to Fang, for most successful start-ups IPOs have historically tended to be the most common way to cash in on investments—the Zero2IPO Research Center put the figure at 89% for 2011. However that is changing, in part because of the IPO freeze, but also because Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent are leading the way in mergers and acquisitions (M&As), while in 2013 the number of venture capital-backed M&As increased to 20 from 11 the previous year according to Ernst & Young.

"Some [M&As are] strategic, increasing their distribution channel—Baidu really wants to increase their source of distribution and their users," says Fang. "Very rarely some people acquire for talent, I think it's very rare… If it's something [big tech companies] could do internally, and there's not that much of a barrier, then they would probably just prefer to do it themselves."

This underscores the fact that copycatting remains a real threat to start-ups, even if in some ways it was a boon to Shenzhen's development. Imitation can come from rival start-ups or from China's technology giants, with the effect of not only undermining business models, but also skewing the ways in which acquisitions happen.

According to Embley, China's big companies have the resources to easily recreate the work of other companies, which, in turn, allows them to dictate unfavorable terms to the companies they look to acquire, unless they are fortunate enough to have a critical, defendable piece of IP, or the crucial knowledge, resources or relationships needed to make it a success.

"If you don't have all of that to defend what you're doing, and they have to have you, they can just very easily recreate the game or the social app or whatever the hell it is you're doing, and they've got the resources to make everyone go and download it and totally destroy you," he says.

Another driving force in this dynamic is the scale of China's largest internet companies and their desire to have a presence in all areas of the market, while for smaller companies easy access to capital, an aversion to risk and the ease with which imitation can be done leads to a rash of companies in the same field, each offering similar iterations of the same basic idea.

Weak IP enforcement also makes China less attractive as a base for high-tech companies. "My assumption is that weak enforcement of IP laws is the result of deliberate government policy rather than an inability to enforce the laws," says Gupta. "Such a policy… slows down China's move up the technology ladder." He points out that technology companies have far bigger R&D operations in India, even though China spends more money in this area.

The state of education, both in formal terms and that of mentorship from older, successful entrepreneurs (a key aspect of Silicon Valley's ecosystem), also provides a challenge to China's capacity to develop a Silicon Valley rival. With a system largely based on rote learning and exam preparation, the Chinese school system does little to engender creative thinking, while the lack of experienced mentors makes it harder for inexperienced entrepreneurs to navigate a challenging business landscape.

"The entire education system is not optimized for very fast-changing technologies like computer science," says Ma. "The number of qualified developers, I think, is lower—it's lower than a lot of people think in China." Embley agrees that education isn't what it could be: "[Chinese children] aren't raised to be good entrepreneurs."

The issue of mentorship, and the associated problem of a lack of quality C-suite level talent, might be solved by the trend of Chinese people returning to China after going abroad. "A lot of the ones for example that we've invested in, they've worked at Facebook or Google and they came from Stanford, so they've seen the best in terms of technology… and they've been at the best tech companies," says Fang.

China hasn't yet been able to match Silicon Valley in the areas of disruptive innovation and numbers of top level companies— China ranks 29th on the 2014 Global Innovation Index, below the likes of Slovenia, Estonia and Malta—but despite that, it has the money, and there are still plenty of signs of energy and enthusiasm. The fact that this energy isn't all concentrated in a single place also undermines assertions that any one location can claim to be China's Silicon Valley equivalent.

"Generally speaking any comparisons to Silicon Valley are wrong—there is no other Silicon Valley at all," says Embley.

But if Silicon Valley has claims to uniqueness, so does China's southern tech hub. One day, we might ask where a country's Shenzhen is.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]