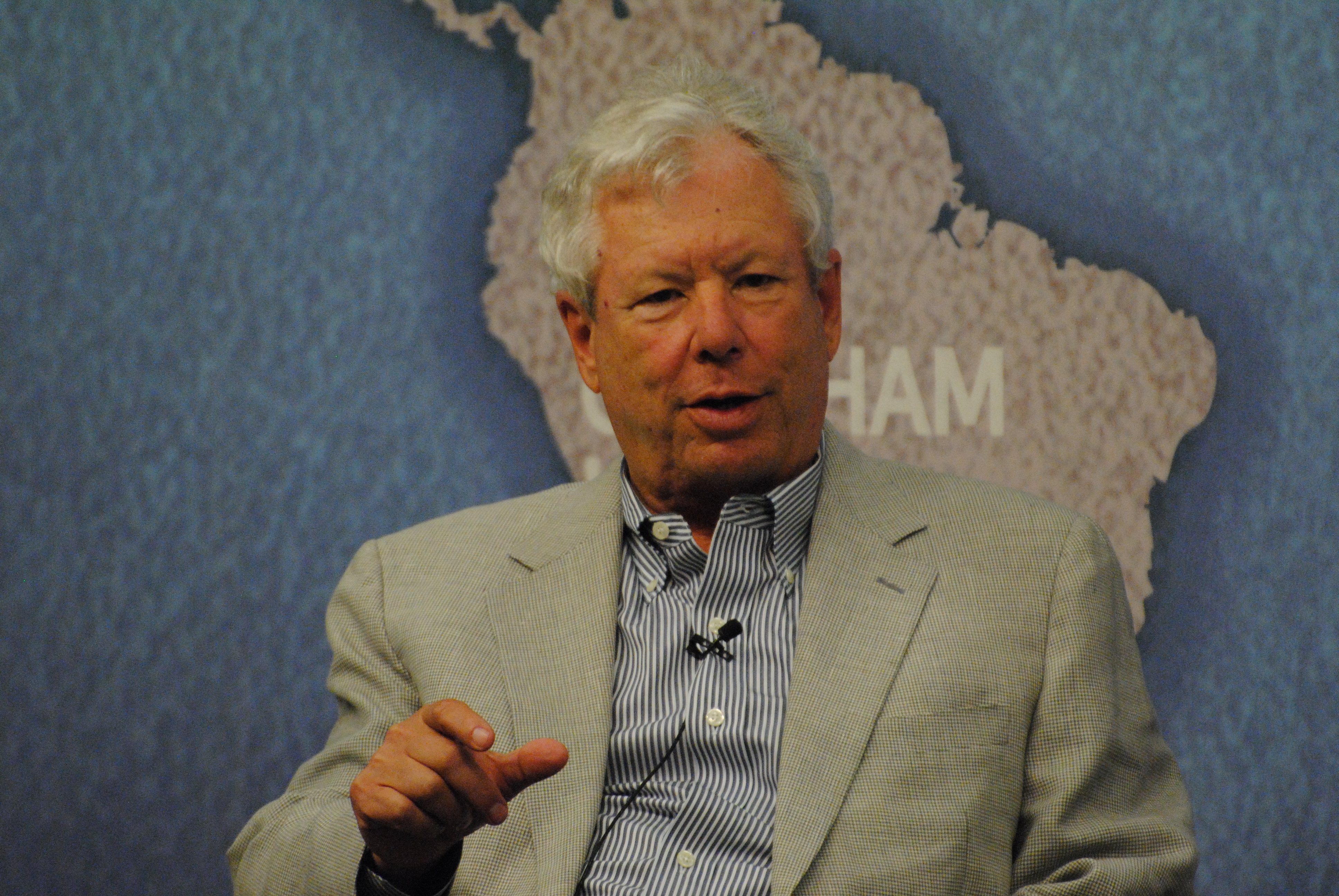

(Prof Richard Thaler, Image by Chatham House, London via Wikimedia Commons.)

In his book Nudge (coauthored with Cass Sunstein) , Richard Thaler, the latest winner of Nobel Prize in economics, made a case for what he called ‘libertarian paternalism’. His argument went like this. Human beings don’t always take decisions that are in their own best interests. They smoke, they eat junk food, and they invest in ponzi schemes. But, it is possible to nudge them into taking right decisions. A school canteen, for example, can nudge students to go for healthy food by arranging the food on the counter in a way that makes it more difficult to grab junk. His views has a strong influence on policy makers. The most famous example is UK’s Nudge unit, which was set up in 2010 (and privatised eventually). The unit looked at ways to increase tax collections, reduce medical prescription errors, get more people to vote among others using Thaler’s approach and insights.

It’s easy to see why such interventions can be important for India. Consider accidents on railway tracks. In Mumbai, hundreds of people lose their lives every year trying to cross the tracks. There are hotspots. About 65% of these deaths happened near 8 stations. Erecting fences were of no avail, because people simply removed them to save themselves time and effort. Of course, no one wants to get run over by trains. It’s only that people regularly underestimate risks. FinalMile Consulting, which uses Thaler’s insights (among others) to effect changes in behaviour took up one station to study the problem, and suggested railways to make a few changes - photographs of frightened persons to trigger feelings of fear, and hence alertness; yellow lines on the ground; staccato horns from the engine drivers instead of one long tone. The accidents dropped dramatically.

A few years ago, I accompanied Biju Dominic, founder of FinalMile to an unmanned railway crossing near Bangalore, to see what his company working with Railways did to bring down the accidents. The problem was similar - people, especially those in large SUVs underestimated the risk of getting run over by the trains. On the location I noticed the speed breakers were not parallel to each other, which meant the drivers of vehicles got a jolt as they approached the crossing, there were steel fences that created a feeling that it’s a danger zone. Again, they were nudging people to be careful while crossing the track.

Application of Nudge principles need not be limited to averting accidents. It can potentially solve a range of issues. Consider toilet usage in India. Indian government says that percentage of households with toilets has gone up from 38.7% in 2014 to 69.04% in 2017. However, getting people to use them is turning out to be difficult. A couple of villages in Rajasthan actually paid people to use toilets. Some districts tried to solve it by coercion or public shaming - which is perhaps paternalistic, but definitely not libertarian. Yet another problem that India faces is more serious - tuberculosis. According to a recent report in Lancet, 12.4% of all tuberculosis patients will have the multidrug resistant variant by 2040. In general, antibiotic resistance is increasing in the country, thanks in part to those who stop taking the drugs once they feel better. Insights from behavioural economics can potentially help solve some of these problems.

This is the promise of behavioural economics. By understanding and combining psychology and economics, we can learn to design systems that can make the world a better place. The subtitle of Thaler’s book captures this promise: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness.

The age of digital nudges

When Thaler published his book in 2008, there were 50 million internet users in India. Today, there are more than 450 million. Four years down, in 2012, there were 44 million smartphones in India. Now, the number is well over 300 million, and is growing fast thanks to lower device prices. Data price is dropping too - especially after the launch of Reliance Jio. More transactions are moving online - communications, shopping, payments, learning and so on. For a lot of things that we do today, the primary interface is a screen - that of laptop, mobile, smart TV. Last year, when The Pokemon Company, a part of Japanese multinational Nintendo, launched a mobile, augmented reality game called Pokemon Go, it sent tens of thousands of people going around looking at the real world through their smartphones. Recently, Mark Zuckerberg came under heavy criticism after he posted a video that showed him ‘experiencing’ Puerto Rico floods in virtual reality. All these point to one thing. We are neck deep in the world of digital nudges.

We don’t need to look beyond ourselves. We have consciously let our phones to wake us up on time, to remind us drink water at regular intervals, and if we are sitting on our desks for too long, to urge us to take a walk. It warns us when we are terribly falling short of our 10,000 steps a day or six hours of sleep goals. It reminds us of our meetings. It tells us to pick up milk and vegetables when we are passing by our grocers.

But, often, our phones exceed their briefs. They nudge us to do things that we never asked them to, acts that are potentially bad for us (and probably good for one of the digital services we use - for free.)

“There's a hidden goal driving the direction of all of the technology we make”, design thinker Tristan Harris told his audience at a Ted talk in Vancouver earlier this year, “and that goal is the race for our attention”.

Harris, a former Googler whose job title was design ethicist, is not happy with the direction it is taking us. It’s easy to see why. Big tech companies are making design choices that persuade us to spend our time not on what we want in our lives, but on what is profitable for them.

A recent Guardian piece featured Harris, and people like him who have worked in big tech firms, and are acutely aware of the impact they can have on us and on our society. Facebook notifications, the essay informed us, use red color, rather than blue, because we are more likely to respond to a notification in red, rather than blue. Apps use the pull-to-refresh mechanism because people respond to it in the same way respond addicts respond to a slot machine in a casino. In the next pull, who knows, we might just hit a jackpot.

What’s worse? These handful of tech companies are combining the large amounts of data they have collected from us with disruptive technologies such as Artificial Intelligence. This combination can potentially extract so much of knowledge about us that Thaler’s research and insights will seem crude in a not too distant future. If Thaler’s books can tell us what nudges people in general, Zuckerberg’s Facebook actually knows what can nudge a specific person in a specific direction - at a specific point of time.

It’s not entirely bad. For example, Facebook uses some of this access and power to prevent suicide. But, it would be naive to forget that Facebook is a big ad machine, and exists to serve the interests of its advertisers - even if they are some Russians trying to persuade Americans to vote in a certain way.

Nudge Vs Nudge

Like knife, Nudge can be used for good as well as bad. It’s true that governments, social sector and businesses can use it for better social outcomes. But, it’s also true that the very same institutions can use these techniques further their own interests at our cost. The challenge for us is to benefit from these techniques while protecting ourselves from the risk of harm.

What can we do about it?

Being aware - having the knowledge of how persuasion techniques work - may not help. Robert Cialdini, one of the best known experts in the field of influence, and who has condensed the various persuasion techniques that people have historically used into six principles - has said he himself is not immune. He has been conned too. Thaler, in his book, says how the design of a door his lecture hall - used by professors and students day after day - still nudges them to use it in the wrong way.

What if we use the same nudge principles to protect ourselves from attention seeking technologies? For example, move Facebook and Twitter away from the first two or three screens (just like how a school canteen places junk food in hard-to-access spots). Turn off notifications. Fill in first two screens with something we really want to do: Kindle; Apps of media organisations we respect; Brain training apps. And most importantly, like Satya Nadella once said, your favourite To Do app. That would remind us there are more important things waiting to be done, than Twitter or Facebook.

We can take help offline too. For example, a couple I know made a deal between themselves that dramatically brought down their online shopping. The deal was simple. If the husband wanted to buy something he would ask his wife to order it online, and vice versa. Most of the impulse purchases simply disappeared, and they say they feel closer, like I how they felt when they got married 16 years ago.

They are fortunate. For every positive story, I have heard ten stories of people saying these techniques haven’t worked for them. Like a junkie, they swipe fast to the last screen to check Twitter, or change the plugin setting to let them check Facebook once. And then once more. And so on.

If there is one big learning from the Guardian piece, it is this. We need more to take more radical steps to counter big tech. (Is it possible that they know more about us than we do, that their design - based on our data - is more effective than any that we could design?). The tech insiders that Guardian interviewed have blocked sites, uninstalled the apps. My friend Charles Assisi uses an app called Moment to restrict the time he spends on his mobile phone. Steve Jobs restricted the use of iPad at his home for his children. So does Jeff Bezos.

Recently, listening to one of my friends, Anand V, a total tech insider, but one who refuses to carry a mobile phone or to own a car, speaking about why he made those decisions, it struck me that it’s not just about using a few plugins or imposing restrictions on ourselves after reading a news report or an essay. It’s about having a philosophy - shaped by experience, refined by introspection and strengthened by healthy discussions. It’s about deeply understanding what’s important for us, and having the discipline to pursue it, find it and guard it. It’s about unwillingness to let other people determine our lives.

But, it’s not just about our personal lives. Big tech’s pursuit to grab our attention is also having a huge impact on our society - manifested in the polarisation and outrage we see on social media day after day. If Rabindranath Tagore were addressing internet in Gitanjali, he would have written: “Thou hast brought the distant near and made an enemy of the stranger.”

Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness will need more than a nudge.