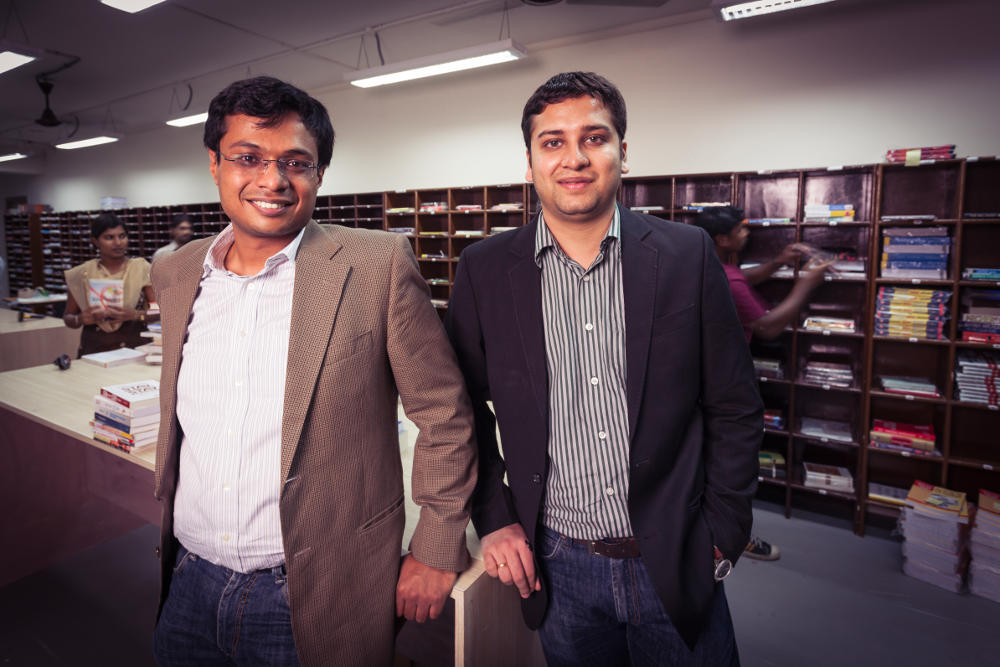

[A file photo of Flipkart co-founders Sachin Bansal (left) and Binny Bansal.]

Less than six months after their momentous deal with Walmart, both co-founders Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal are out of Flipkart. It is a sad commentary on the hubris and the immaturity that’s gripped India’s high-flying tech entrepreneurs.

Binny Bansal’s sudden, unceremonious exit has raised eyebrows across the entrepreneurial ecosystem in India, particularly in the tech heartland in Bangalore. While he may have been the lesser known of the two Bansals, yet when Walmart bought 77 per cent stake in Flipkart, India’s biggest unicorn, earlier this year, they picked Binny as group CEO, and not Sachin.

Sachin ran the firm with an iron hand and was known to rub people the wrong way. Binny, on the other hand, was affable and the hands-on operations leader. And between them, they became the poster boys of the Indian tech start-up world. And while the $16 billion deal with Walmart ought to have catapulted them into iconic status, yet, less than six months later, both find themselves out of the company they co-founded back in 2007.

Since the full details weren’t in the public domain, there have been three kinds of public reactions to Binny’s exit. One, the needle of suspicion pointed towards Walmart. That it always had plans to take full control of Flipkart—and that Binny became a necessary roadkill in that journey. Two, the board didn’t see him as a leader who could help them turnaround the operations—and stem the mounting losses—and therefore there was an insidious plot to push him out of the company on trumped up charges. Three, a few strident swadeshi activists view this as some kind of a multinational vs desi tussle, however, misguided the thinking might sound.

So which of these versions does one believe? First, here are the facts, based on what we know so far and my own research. Two years ago, Binny had an extra marital affair with a former employee. The relationship went sour and there were allegations of extortion and blackmail. Binny tried to manage the situation on his own by employing a security firm. He chose not to keep the company informed, perhaps because he believed this matter was in the personal domain. But that’s not the “serious personal misconduct” that the Walmart alludes to. We’ll come to that in a bit.

In July this year, the complainant sent a letter directly to Doug McMillion, the global CEO of Walmart’s HQ in Bentonville, Arkansas, making allegations of sexual assault against Binny. That prompted Walmart to ask Gibson Dunn, a global law firm to do a thorough and detailed investigation. The investigation found that the allegations of sexual assault against Binny were unsubstantiated and that the relationship was consensual. But it found a serious lapse: An investigator from the security firm employed by Binny had called the woman for a meeting and had tried to physically assault her, but she escaped. When the lady informed him about the assault incident on email, in order to deal with a potential criminal case, instead of responding to her, Binny employed yet another security firm to put a lid on the matter. The second security firm tried to hammer out a monetary compensation. But it seems the lady demanded a much higher compensation.

Why this matter resurfaced again in July this year, nearly two years after the event, remains a mystery, especially the decision to write to the Walmart global CEO. Interestingly, a copy of the complaint was also marked to Sachin Bansal, who was apparently among the handful of people who knew about the entire chain of events. After the Walmart takeover, the two Bansals were no longer on talking terms.

When the full report of the detailed investigation was presented to him, Binny perhaps knew the die was cast for him. The biggest issue was that he had shown poor judgement by not disclosing the matter during the due diligence, which is usually a standard clause during such negotiations. And for a global firm such as Walmart, this posed a grave reputational risk. And it typically treated such matters strictly by the book. And so Binny had no option but to resign.

As it is wont to do, Walmart had to put out a statement to the stock exchanges, to prevent any class action suits in future. (Later, the same day, however, Binny issued a statement expressing surprise at the allegations, claiming they were unfounded.)

At the same time, Binny appears to have been given a soft landing. Despite his so-called serious lapse of judgement, he still gets to keep his board seat. Perhaps partly because he is legally is entitled to one, commensurate with his 4 per cent stake.

Now, let’s step back and consider the bigger picture. In May this year, when Walmart made its move, there was plenty of hoopla and hype around the biggest exit in India’s start up ecosystem. Even before that, the Bansals were already seen as rockstars with numerous start up awards being conferred on them by media like confetti.

Sachin’s fate was sealed immediately after the Walmart deal was signed. He assumed that he would be given a larger role in managing the company—and also demanded that his stake, which had been significantly diluted, be restored to a higher level. Tiger Global and the other investors responded by easing him out.

Binny, however, didn’t exhibit the same kind of hubris. But where he slipped up badly was in gauging the level of transparency and governance that is expected by a global strategic investor.

The circumstances under which the so-called tech poster boys have been eased out of the company is clearly an embarrassment that Indian entrepreneurial ecosystem could have done without.

When power, discipline, and cultures collide

Inside both Flipkart and Walmart, Binny Bansal was seen as a swell guy—and best placed to help tide over a seemingly difficult transition. So why did the retail giant from Bentonville send him packing? The full inside story

By Indrajit Gupta with NS Ramnath

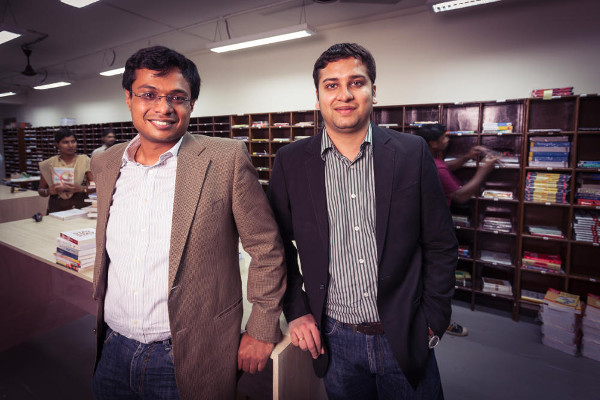

[A file photo of Flipkart co-founders Sachin Bansal (left) and Binny Bansal. The exit of both co-founders after the investment by Walmart has much to do with the fast and furious startup culture at Flipkart colliding with the conservative, family-values-driven work ethic of Walmart.]

The decision to let go of Binny Bansal, Flipkart’s co-founder and group CEO was painful. This isn’t how the senior team from either Walmart or Flipkart had imagined things would pan out. Binny’s reputation was not just that of a nice guy, but also a person who could keep calm when the pressure mounted. In turn, it allowed room for the leadership team at Flipkart under its CEO Kalyan Krishnamurthy to operate well.

That is why when an email landed in everyone’s inbox on Tuesday, November 13, announcing Binny would step down from his role, emotions at Flipkart ranged from disbelief to shock. No one from the local offices at either Walmart or Flipkart had an inkling this was coming.

In fact, nobody at Walmart India’s headquarters in Gurgaon or at Flipkart’s in Bengaluru was involved in conversations with Binny.

Newspaper reports suggest that Binny was informed about the findings of a report on Monday—and that he articulated his shock at its contents and slammed it as unfounded. Perhaps, he was clutching at straws. Then, a front page story in The Economic Times appeared on Wednesday. It quoted anonymous sources and suggested not all the content in the investigation had been shared with Binny.

Senior people whom we spoke to said this was untrue. Instead, they pointed to how meticulous the investigation was. It was managed directly by Walmart’s global office, led by Judith McKenna, CEO of Walmart International. McKenna is responsible for all of the 27 markets outside the US where Walmart is present. She reports into Doug McMillon, the global CEO of Walmart. Not even Walmart’s Canada and Asia head Dirk Van den Berghe, who sits on the board of Flipkart, was a party to these conversations.

They said the full report was placed before Binny, its findings were laid out before him, and it was made clear the facts it contained had been gathered based on conversations with key stakeholders. Binny was specifically told where he had shown serious lapses in judgement. After hearing the contents of the full report, there was no other option for him but to agree to resign. That said, those in the room asked him to sign off on a communication plan.

This included a statement that would go out from Walmart announcing his exit and an email from him as well. Walmart did the best it could to soften the blow. Those in the room saw it as a personal issue that had already impacted his marriage badly. Besides, no one within Walmart and Flipkart had any animosity towards him either. That is why the final draft of the note from Walmart went easy on the details and simply suggested that Binny demonstrated several lapses in judgement.

The 37-year-old would be forced to leave a firm he had co-founded out of a two room apartment in Koramangala, Bengaluru, in 2007, nearly a year before his term was slated to end.

(We have sent detailed questions to Walmart-Flipkart, Binny Bansal and Sachin Bansal on the events that unfolded. Binny Bansal responded promptly but eventually declined to respond on specific questions. In the interests of transparency, we have shared a PDF version of our correspondence with him here. For the others, we will update the story once we hear from them.)

Fixel’s fix

The price Binny has paid seems high to many in India. Is the punishment commensurate with the crime, they ask. After all, it isn’t uncommon for CEOs to be pardoned after similar lapses of judgement. The case around Rakesh Sarna, former CEO of Indian Hotels, a Tata group company, is still fresh in public memory.

Then there are other cases that don’t even make it to the surface for various reasons. Sometimes such scandals are swept under the carpet, especially if the leader is a super achiever. Even in an iconic company like Infosys, the leadership team led by NR Narayana Murthy and Nandan Nilekani did not disclose details of sexual harassment allegations against Phaneesh Murthy for almost a year.

Some have argued that Walmart had a knife ready for Binny Bansal and that this case was part of its plan to ease him out. This is unlikely and fails to answer a big question: If that were the case, wouldn’t it have packed off Binny along with his co-founder Sachin?

Fact is, Walmart wanted him to stay because he had a reputation for being a better team player. All media reports suggest he was indeed playing the role to ensure the continuity Flipkart needed when in transition.

Much before Walmart arrived on the scene, Tiger Global’s Lee Fixel had started to clear the deck

Besides, there is another issue, often forgotten. Much before Walmart arrived on the scene, Tiger Global’s Lee Fixel had started to clear the deck. While he liked the founders, Sachin in particular, he soon realised the duo did not have the mental muscle to take Flipkart to the next level, and fight big battles against a global giant like Amazon.

Fixel masterminded a smooth transition that seemed to suit everybody. He brought in a lieutenant from Tiger Global—Kalyan Krishnamurthy, a veteran described as canny and smart by everyone who has interacted with him.

Sachin and Binny were offered ceremonial roles. They would show up at carefully co-ordinated media events and be the public face of the firm—Sachin, more than Binny. But there was hardly much of an operating roles left for them.

This is why when Walmart took over, it wanted to preserve the arrangement. With one change. Sachin would have to leave (why is something we will come to in a bit). Binny would now become the public face of the company, with Krishnamurthy focused on the operations.

Whether Binny was ready to take on a more public role, he had to step into the void. Consider, for instance, that time when he appeared at the high-profile 2018 Code Commerce conference, organised by Recode in San Francisco in September. He was pitchforked into the hot seat taking questions from the publication’s Senior Editor Jason Del Rey.

Yet, his answer to one of the questions indicated that everyone was in it for the long term.

“We needed a lot more strategic capital backing us which was way more patient and long-term and not really looking for mid to short-term returns because as we've all seen these platforms really start making profits at a large scale and start being valuable at a much larger scale. In Walmart we found a partner which was willing to be in spirit an investor although an owner but in spirit come on board as an investor,” he said.

There was no indication in any of his answers that within months, Flipkart would have no place for him.

[Flipkart CEO Binny Bansal | Full Interview | 2018 Code Commerce]

By all accounts, Binny did not come in Krishnamurthy’s way during his stint as Group CEO.

Walmart has consistently earned the ire of communities, activists, and small traders

Yet, doubts linger—even among journalists and analysts—that Walmart conspired to expel Binny.

Much of this has to do with Walmart’s public image in the US and markets in other parts of the world. It has consistently earned the ire of communities, activists, and small traders and is seen as a “Big Bad Wolf” that leeches off community services and uses scale to turf out smaller retailers. While many attempts have been made to burnish its reputation in recent times, it isn’t easy to shake off perceptions. The title of a 2006 book captures the way many still perceive the company: The Bully of Bentonville.

Things aren’t different in India. Many people don’t trust Walmart for various reasons. And when any narrative emerges that has to do with Walmart and the public exit of a big name local entrepreneur, rumour mills go into overdrive. This explains why many have tried to ascribe hidden motives for Walmart’s actions. Then there are avid Flipkart-watchers who want to believe Sachin and Binny’s exit was engineered by Krishnamurthy.

Loose talk, it is. Nothing more.

Why did a quiet, reticent middle class boy from Chandigarh succumb to more lapses in judgement?

Two questions then follow.

- Why couldn’t Walmart simply downplay Binny’s so-called lapse in judgement and perhaps reduce the level of punishment?

- Why did a quiet, reticent middle class boy from Chandigarh with an education from IIT-Delhi, by all accounts happily married, on the verge of becoming father to twins, engage in an extra marital affair, and then succumb to more lapses in judgement in 2016?

The answer perhaps lies in that this was the fast and furious startup culture at Flipkart colliding with the conservative, family-values-driven work ethic of Walmart.

The Winners’ Curse

When Sachin and Binny started out in an apartment in Koramangala, they were down-to-earth, quintessential geeks, and passionate about Flipkart. To fulfill their first order, Binny had to go to every bookstore in Bengaluru to hunt for a copy a customer had ordered. (He found one in Sapna Stores in Indira Nagar). They weren’t just coding. They were packaging and posting the books as well.

When Ramnath met them a few years after they started out, they had hired a few people, raised money from Accel Partners and Tiger Global, and moved into an entire building in Koramangala. The place was emerging as a hub for startups. And Flipkart had a buzz around it.

Sachin was like a little child eager to show his latest toy: a computer program that helped take stock of books available with vendors across the country. They were focused on what may it take to build a strong backend.

The company was beginning to attract ambitious engineers keen to participate in India's internet story. To do that, they burnt the candle at both ends. And the market held huge promise. Flipkart started to expand into new product lines. It had no place to go, but up. Sachin and Binny were acutely aware of the potential and wanted every piece of the action.

In 2012, when both of us were at Forbes India, Rohin Dharmakumar, one of our colleagues based in our Bengaluru bureau, now CEO of The Ken, a subscription-based digital media startup, took a hard look at Flipkart’s culture. He went on to write: “Let’s put it this way. Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal have balls.” It was intended as a compliment.

He then filed a caveat. “But if you’re the kind who think audacity and balls as the foundation on which hubris and foolhardiness are built, then Sachin and Binny Bansal’s Flipkart begins to look like an entity skating on thin ice.” (His words now sound prescient). The cover carried a 3D image of Flipkart’s logo—a shopping cart.

But there was a twist in the image. The cart was broken.

Soon after the magazine hit the newsstands, a furious Sachin wrote a long note arguing Rohin and Forbes India had got it all wrong. Much deliberation later, Indrajit, the founding editor of Forbes India, wrote back explaining the magazine’s stance and placed it in the public domain. Hell broke loose.

For anyone following the debate, it was clear the Indian startup story had reached a certain stage in its growth. Flipkart was beginning to evoke passion of the kind that was on display during the first internet boom days. Sachin and Binny Bansal were the poster boys of technology-driven entrepreneurship in India.

They had spunk, passion and displayed how entrepreneurial ventures can be spurred. It was inevitable that they fire public imagination of startup founders not just in Bengaluru, but across India.

In 2013, Sachin was voted “Entrepreneur of the Year” by the Economic Times. When he walked to the podium to accept the award from P Chidambaram, then the finance minister, he delivered a short acceptance speech. It may not be a polished performance. But it seems Sachin made a mental note that he needed coaching on public speaking, says a senior executive who worked directly with him. And in the next couple of years, the change was perceptible.

But, whatever the stalwarts seated in the front row may have thought of that short encounter with India’s hottest startup founder, the reactions from those at startups was different. Sachin and Binny were heroes. India badly needed heroes like them.

The wealth, power and adulation was heady

By 2015, they had got into the Forbes India rich list, each with a networth of $1.3 billion. But it was not just the money. A year later, Time magazine included them in its list of The 100 Most Influential People in the world. And later in the year, in Singapore, where the company was listed, The Straits Times conferred upon the duo its much coveted title of The Disruptors.

The wealth, power and adulation was heady. Sachin would get mobbed. Young tech talent queued up to join Flipkart. The chemistry between the two, say insiders who worked there, was amazing to watch.

Sachin could be surly and passionate at once. His temper tantrums were legendary at the workplace. But, a senior executive who reported to Sachin told us, Binny was the calming influence. Together, they exuded energy and could understand each other in ways brothers couldn’t. Binny admired Sachin for his vision and Sachin trusted Binny to anchor operations.

Their families had gotten close too. Their wives were confidantes to each other. And when Sachin decided to walk away from his marriage, Binny and his wife did all they could to bring the couple together again.

Through all these, pressure at work was mounting. By 2015, investor expectations were sky high.

With every additional round of funding, Flipkart had to manage a set of investors with different backgrounds, agendas and timelines. On the one hand, it had pure play investors such as Tiger Global and SoftBank. Then on the other, large organisations such as Microsoft and Tencent were invested as well. Besides, markdowns by mutual fund investors such as T Rowe and Morgan Stanley in 2016 hit media headlines.

Amazon had started to make its presence felt as well.

Juxtapose all of these against each other:

- The media and startup ecosystems treat you as a demigod.

- Investors expect you to behave like a demigod too and perform miracles as well.

How many people may have the mental muscle to stay grounded?

Sachin’s middle class values that defined the early years gave way to an arrogance that comes with leading one of the most well-known entrepreneurial ventures. His personal life continued to be rocky. There were reports trickling in of the couple indulging in public spats at the Grand Mercure hotel, located in Koramangala.

Inside Flipkart, while senior professionals were joining, they were struggling to fit into the culture. But Binny, a team player as always, tried to be the rock that held Sachin and Flipkart together.

On his part, Lee Fixel had placed much faith in Sachin. He would fly Sachin down in private jets to meet investors in the US. Fixel hired Rubenstein, a public relations firm, to set meetings with editors of leading publications. But for reasons best known to him, after agreeing to get on conference calls, Sachin would often cancel media meetings at the last minute. On one occasion, he was scheduled for an interview with the Editor of Bloomberg in New York, and it turned out to be a no-show. Fixel didn’t like that.

What nailed Sachin’s fate though was a string of bad decisions. In 2015, for instance, he decided Flipkart ought to be made available to users only as an app on their mobile phones. Not everybody was convinced—Binny included. Sachin misread the growing concerns as well about net neutrality violations in India, and went ahead to make Flipkart app a part of Airtel Zero. The plan backfired. Flipkart had to take a U-turn.

Fixel’s faith in Sachin took a hammering and in January 2016, he inducted Krishnamurthy as CEO of Flipkart. It was a shocker to Sachin.

And Binny. Because he had personal battles to wage as well.

In 2016, his wife Trisha got pregnant. In keeping with tradition, she took time out to be with her parents in Delhi to deliver their twins. During her absence, Binny got into a relationship with a former call centre executive who had left Flipkart in 2012. She connected with him after a long while after joining an event management firm.

When Trisha got back home, she discovered what transpired and forced Binny to end the affair. In attempting to do that, things went sour and the jilted woman threatened to go public. Binny panicked and took a series of wrong decisions.

They were also facing issues that sometimes come with too much power—and too little discipline

By the time Walmart got into the picture, Sachin, Binny, and Flipkart had travelled a long distance. Flipkart was no longer a startup operating out of an apartment. It had over 7,000 people. The campus it operated from was a flashy one—with sections based on themes ranging from Bollywood to cricket and fashion to tech. During demonetisation, employees had access to an ATM machine right inside the building. Sachin and Binny were not only billionaires and lionised everywhere, they were also facing issues that sometimes come with too much power—and too little discipline.

Flipkart was facing multiple issues. Mutual funds had demarked it and Amazon was bulldozing its way into India, among other things. But Sachin and Binny would be vindicated when Walmart bought into the company, valuing it at over $20 billion.

However, Walmart’s entry would also mean the founders’ exit. This, because most people in the startup ecosystem are obsessed with revenues, scale and valuation. They seemed to have ignored one thing: Culture.

[On ET Now Startup Central, Haresh Chawla and K Ganesh discuss the implications of Binny Bansal’s exit. The show was based on the Founding Fuel story.]

Culture eats valuation for breakfast

A senior executive when he first arrived at Walmart’s Bentonville HQ was stunned to see the structure. It looked like a gigantic warehouse—and had only 10 windows. One of America’s largest enterprises was built on the principle of frugality. Sam Walton ensured it stayed that way.

Senior executives were encouraged to stay at three or four star hotels, at best. They received a strict $40 meal allowance, even at senior levels, with specific limits for breakfast, lunch and dinner. If you saved money at breakfast, it couldn’t be added to the lunch kitty. It simply meant, you saved money for the company.

Back in the old days, even as one among the richest Americans, Sam Walton would tour his stores without carrying his wallet—and had no compunctions about borrowing money to buy a cup of coffee. Walton liked to say that he learned how to value a dollar even as a kid.

Leaders were strictly advised to shun ostentatious behaviour. They lived simply and dressed down. There is a story about a senior executive who built a fancy mansion on top of a hill. He was quietly asked to leave the company. “We've had lots and lots of millionaires in our ranks. And it just drives me crazy when they flaunt it,” Sam Walton wrote in his book, Made in America.

They were not ‘corporate’ values. They were values for life

“It's great to have the money to fall back on, and I'm glad some of these folks have been able to take off and go fishing at a fairly early age. That's fine with me. But if you get too caught up in that good life, it's probably time to move on, simply because you lose touch with what your mind is supposed to be concentrating on: serving the customer.”

They were not ‘corporate’ values. They were values for life. There was emphasis on a God fearing culture, and visiting the church was essential to your growth within the company. And if you went to the same church as one of the senior bosses, it improved your chances of being promoted. Most folks at Walmart were lifers who had risen up the ranks from cart pushers and check out clerks, including the current CEO Doug McMillon. Upholding family values was seen as critical. And extra-marital affairs were strictly frowned upon. Leaders in any of the businesses were expected to walk the talk.

It is very different from the brash devil-may-care culture defined by Silicon Valley leaders such as Mark Zuckerberg or Travis Kalanick. But those are the companies that attract the best technology talent. Now, the decades old Walmart culture is showing signs of change at the margins. Walmart needs to transition into blended commerce to stop the Amazon juggernaut. But attracting tech talent has been a challenge. It upped salaries and chose to locate its e-commerce arm at San Bruno in California, far away from the bureaucracy of Bentonville.

Marc Lore was inducted to head its e-commerce business through its acquisition of Jet.com. And more recently, some of those e-commerce initiatives like its Order online and Store Pick Up models are starting to deliver results.

Similarly, Walmart Labs is based out of Sunnyvale, California.

At the same time, the transition from Rob Walton, the founder Sam's son to Greg Pennar, Rob's son-in-law as Walmart's new chairman has brought significant cultural changes at the top. For one, Pennar is known to be flamboyant and not averse to private jets, something unheard of in Walmart's culture. It is now common to find expensive cars in the parking lot at its headquarters in Bentonville.

While the elephant is learning to dance, a mahout is in place to ensure the steps it takes are deliberate and measured

The changes though are gradual. The family carefully handpicked a loyalist like Doug McMillon to retain its core values. So while the elephant is learning to dance, a mahout is in place to ensure the steps it takes are deliberate and measured. Leaders, who head Walmart’s businesses around the world are expected to strongly uphold family values.

This balance between change and stability, innovation and conservatism was something that Sam Walton grappled with in his own lifetime. “This is a big contradiction in my makeup that I don't completely understand to this day. In many of my core values—things like church “and family and civic leadership and even politics—I'm a pretty conservative guy. But for some reason in business, I have always been driven to buck the system, to innovate, to take things beyond where they've been. On the one hand, in the community, I really am an establishment kind of guy; on the other hand, in the marketplace, I have always been a maverick who enjoys shaking things up and creating a little anarchy.”

The big lesson was that it was possible to be innovative in business while believing in the core values of frugality, family values, and restraint. “I would walk a million miles with someone who had job performance problems, but wouldn't take the first step with someone with an integrity problem,” Sam Walton once said.

This kind of culture is not alien to Bengaluru, but it was to the new generation of startups that Flipkart belongs to

This kind of culture is not alien to Bengaluru, for there are companies like Wipro which follow a similar philosophy, but it was somewhat alien to the new generation of startups that Flipkart belongs to. And it was this culture that Flipkart would become a part of after Walmart’s investment.

In such a culture, the idea that a group CEO in a newly acquired company back in India would engage in an extra marital affair and then show significant lapses in judgement would have sent shock waves among the family and top leadership in the US. And it was bound to be taken far more seriously than possibly in any other company in the US. If the charges were proven, even McMillon wouldn't be able to do much to save the person. The execution would be swift and decisive.

And so it was. By end October, once the investigation report was ready, it was a matter of time before Binny Bansal would have to pack his bags and leave Flipkart forever.