[From artyfactory.com]

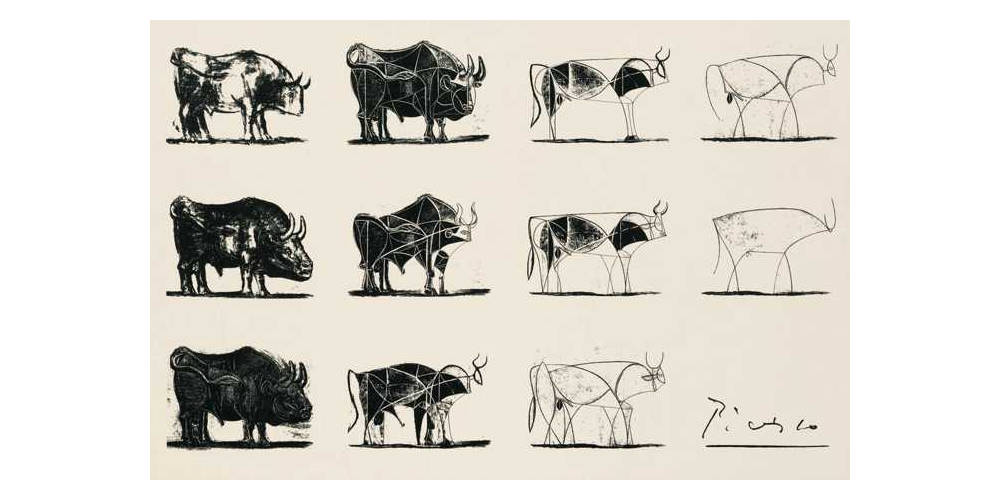

In 1945, Picasso worked on a series of lithographs that give us a glimpse of the process it probably takes to arrive at the spirit of a subject. As you see the images one by one, you realise that the final image—simple lines—can stir up your emotions even better than a detailed, academic representation of a bull. The series is now a classic. Apple University uses the artwork to explain the company’s pursuit of simplicity.

In 2003, in a series of lectures on BBC, Vilayanur Ramachandran presented a fascinating hypothesis of how art—from Chola bronzes to Picasso’s paintings—works. In the lecture, he talks about an experiment conducted on herring gull chicks by Nikolaas Tinbergen, an Oxford biologist. (Full lecture here.)

“As soon as the herring gull chick hatches, it looks at its mother. The mother has a long yellow beak with a red spot on it. And the chick starts pecking at the red spot, begging for food. The mother then regurgitates half-digested food into the chick's gaping mouth, the chick swallows the food and is happy. Then Tinbergen asked himself: ‘How does the chick know as soon as it's hatched who’s mother? Why doesn’t it beg for food from a person who is passing by or a pig?’

“And he found that you don't need a mother.

“You can take a dead seagull, pluck its beak away and wave the disembodied beak in front of the chick and the chick will beg just as much for food, pecking at this disembodied beak. And you say: ‘Well that's kind of stupid. Why does the chick confuse the scientist waving a beak for a mother seagull?’

“Well, the answer again is it's not stupid at all. Actually, if you think about it, the goal of vision is to do as little processing or computation as you need to do for the job on hand— in this case for recognising mother. And through millions of years of evolution, the chick has acquired the wisdom that the only time it will see this long thing with a red spot is when there's a mother attached to it. After all, it is never going to see in nature a mutant pig with a beak or a malicious ethologist waving a beak in front of it. So it can take advantage of the statistical redundancy in nature and say: ‘Long yellow thing with a red spot IS mother. Let me forget about everything else and I'll simplify the processing and save a lot of computational labour by just looking for that.’

“That's fine. But what Tinbergen found next is that you don't need even a beak. He took a long yellow stick with three red stripes, which doesn't look anything like a beak—and that's important. And he waved it in front of the chicks and the chicks go berserk. They actually peck at this long thing with the three red stripes more than they would for a real beak. They prefer it to a real beak, even though it doesn't resemble a beak. It's as though he has stumbled on a superbeak or what I call an ultrabeak.”

The amazing ability of living systems to respond to something so abstract might help scientists find vaccines for coronavirus faster than before. Vaccines work by training our immune systems to spot and fight bacteria or viruses. It comes from the observation that if you have recovered from a pathogen infection, you are less likely to get it again because your immune system has learned to fight with it. What if you deliberately introduce the pathogen into the human body and let it learn how to fight it? (The parallel here is mother gull feeding the chick.) The progress in vaccine development has been a series of experiments to see what features you can remove from the pathogen, and still trigger the immune system. Thus, over the years, scientists have injected weaker forms of pathogen, dead bacterium or virus, or even a small part of it.

And now, a number of labs are checking if it’s enough to just send in the DNA—the equivalent of the stick with three red stripes. These strands are then injected into a person and that triggers the body to produce antibodies to fight the virus. In fact, DNA vaccines for influenza are already in the human testing phase. A number of labs across the world are taking this approach to fight the new coronavirus as well. It’s expected to be efficient, and cheaper to produce. Just what we need if we want to vaccinate seven billion people.

In fact, we need not vaccinate all seven billion people, because once a large percentage of the population is vaccinated, it makes it safe for everyone, as we have seen in the case of measles. (The resurgence of measles in the US, Europe and other parts of the world also reminds us that if vaccination goes down, the disease might come back).

- Vox has a summary of companies working on vaccines - here

- Stat wonders if Inovio Pharmaceuticals, whose share price has been up since January, has it in them to deliver - here

- A good explainer on vaccines from Boston Children’s Hospital - here

This is the big picture. Coronavirus is growing exponentially. The experience from Italy shows that as the disease spreads, the healthcare capacity—however good it might be in normal circumstances—will be inadequate. The system will struggle. It will mean death for the most vulnerable. It will cease to be a technology/operations problem. It will become a moral/ethical problem.

So, it’s imperative for us to stop it. We have to develop vaccines and cure for the disease. It’s not yet clear how fast vaccines will hit the market—some have said it could take 12 to 18 months, others are more optimistic. It’s also not clear how affordable it will be. Finding a cure might be faster even as scientists build on existing research. The good news is that there seems to be good coordination between government, social sector and businesses. (Cynical take: Unlike Ebola which affected only poor countries—which delayed the development of a vaccine—coronavirus seems to be an equalizer infecting first ladies of Canada and Spain, as well as the President of Brazil. So, resource mobilisation has been easier.)

The big question is how do we flatten the curve? How do we minimise the spread of the disease using a mix of tools we have—personal hygiene (water, soap, sanitisers), social isolation (work from home, cancel gatherings, especially in places conducive to the virus)—and most importantly, health surveillance and testing.

Countries such as South Korea and Singapore managed to contain the damage through clever use of technology, which in normal times would have raised serious questions about surveillance and privacy. Eventually, every country is expected to choose pragmatism over ideology, and in all likelihood there won’t be significant push back from activists when their own lives are at risk. The rest of us, however, will have to figure out a way to ensure that the war-time measures are rolled back once we are out of the danger zone.

Dig Deeper

Coronavirus has been growing exponentially, with China as the epicentre

- How it all started: China’s early coronavirus missteps | WSJ

- A timeline of the coronavirus | NYTimes

- How coronavirus hijacks your cells | NYTimes

China is getting it under control

- Report of the WHO-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (PDF) | WHO

Different countries have been tackling it differently

- Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong have brought outbreaks under control—and without resorting to China’s draconian measures. | NYTimes

- China Vs US, a thread by Balaji Srinivasan | Twitter

- Why is the UK approach to coronavirus so different to other countries? | New Scientist

Meanwhile Italy, Iran and Spain are seeing a rise in infections

- A coronavirus cautionary tale from Italy: Don’t do what we did | Boston Globe

- The extraordinary decisions facing Italian doctors | The Atlantic

- Iran’s coronavirus strategy favored economy over public health, Leaving both exposed | WSJ

- Spain, on lockdown, weighs liberties against containing coronavirus | NYTimes

The problem comes from the mismatch between extraordinary demand and limited supply

- Coronavirus: Why you must act now | Medium

- Why outbreaks like coronavirus spread exponentially, and how to “flatten the curve” | Washington Post

- Don’t “flatten the curve,” stop it! | Medium

In India, the healthcare capacity varies from state to state, district to district

- How prepared is India for a Covid-19 outbreak | Mint

The government response has been different from state to state