[By Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission Belur Math (Public domain)]

Swachh Bharat Mission is three years old. Cities are gearing up for the third edition of the intercity competition Swachh Survekshan. Has the needle shifted in making Indian cities cleaner and healthier?

While quantifying impact is complex—and I’ll come to the reasons shortly—civic technology, mainly information and communication technology (ICT) and internet of things (IOT), can improve governance monitoring and therefore impact. Governments around the world—not just in the emerging economies—are increasingly adopting civic tech.

Monitoring programme performance, governance, and impact is critical given the quantum of monies being allocated—both public and taxpayer funds, and corporate and philanthropic funds. New taxes such as the Swachh Bharat Cess have been created. The Swacchta Hi Seva campaign asks firms to allocate 7% of their corporate social responsibility spending towards Swachh Bharat. Central policies are directing increased spending by cities and urban local bodies on new infrastructure for waste bins, collection, segregation, disposal and recycling. (See box, ‘Waste management: Fixing the links in the chain’.) Smart Cities Mission has allocated additional funding to cities that can be redirected towards municipal solid waste management. There is a lot of focus on capacity building and awareness generation programmes, critical elements of changing behaviour and instituting sustainable change. Estimates suggest that toilet construction and maintenance will be a $62 billion marketplace by 2021 (it is roughly $31 billion currently). Yet, last year, World Bank withheld a substantive loan of $1.5 billion promised to Swachh Bharat Mission (Grameen) due to lack of third party verification of the programme.

Mapping reported progress

The outcome of cleanliness depends on the interconnected behaviours and daily efforts of large numbers of people across government, business, and society. It is a daunting task. Habits that have led to a sanitation crisis have been embedded for centuries. There has never been a sustained focus on this issue, even in the 70 years since independence. The concept has come to the forefront in the media, but habits, perceptions, and behaviours across urban and rural households are yet to change.

Another layer of complexity is that the perception of progress in cleanliness is both subjective and objective.

We experience cleanliness through the cleaner streets and corners of the city we see every day. And that governs our understanding of the change in cleanliness levels. At the same time, government documentation on budgets spent and infrastructure created are available as public records, and show a different story. Third party validation studies qualify and quantify impact assessment in parts, and show the gaps between subjective perception, objective projection, and on-ground reality. Reports show that spending on infrastructure construction needs to increase further to deploy and allocate available budgets. At the same time, the programme often garners criticism and scepticism on spending and impact.

Civic tech can help fill many of these gaps. It makes available granular, real time data and feedback from citizens. Which makes it easier to track performance and correct shortfalls.

Having worked on multiple technology and capacity building initiatives for Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban), including building the entire mission management platform, it is heartening to see the focus on improving governance. Tech interventions, such as the smart feedback system already deployed in 60 cities for monitoring cleanliness of public toilets, are enabling participative governance. The Mission can harness the benefits of seamless data acquisition, data management, Big Data analytics, prognostics, data visualisation, and reporting.

But a lot more still needs to be done. Long-term success will require continued imagination to build innovative solutions, retain committed stewardship, and manage multiple stakeholders effectively.

Increasing accountability through tech-enabled governance monitoring

Global political philosophy has shifted towards outcome-oriented governance. Sustainable Development Goals focus on livability and livelihood. Effectiveness of public spending and quality of last mile public service delivery are critical parameters to monitor, measure and manage institutional performance.

It is not enough to create inclusive policies. It is critical to converge policy and funding with commitment and performance orientation. Government institutions work through distributed organisations consisting of officials, staff, third-party service providers, partners, and NGOs working at national, state and city levels. The entire chain needs to be tracked to ensure performance and impact.

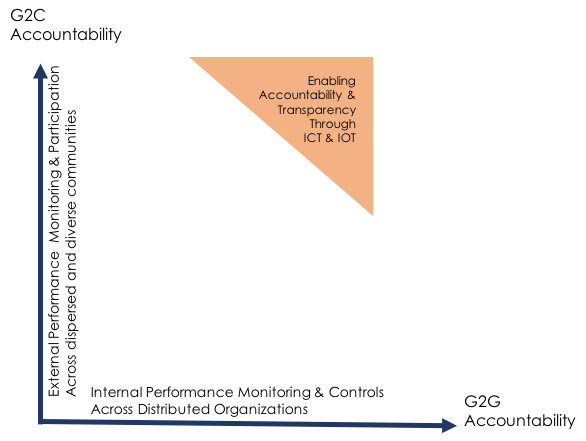

Technology-enabled governance monitoring can be done along two separate axes.

Government-to-government monitoring: The challenge of cleaning India is a massive one—4,041 urban local bodies and numerous staff and stakeholders need to be managed. Each has its set of service providers. Given lack of cohesive data collection and management on national key performance indicators (KPIs), it is tough to assess true progress and manage outcomes and accountabilities. Complicated workflows and data in different formats and channels adds to the problem.

Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) is using a national performance monitoring platform to track the performance and efforts of staff across levels of authority, geographies, and accountabilities. National progress against mission goals such as construction of individual household toilets, door-to-door waste collection, waste-to-energy or waste-to-compost production are being tracked in near real time based on information submitted by cities. Mission leaders can see national-level status and drill down to state and city levels.

The backend of the platform serves as a mission management-cum-performance monitoring engine. The data architecture of the system integrates many-to-many information flows. Status, delays, budgetary allocations and budget deficits of projects and sub-projects come into a single national dashboard. The system allows data-driven and rules-based analytics to create alerts and escalations. Automated reminders are sent when progress submissions are late. This becomes a dynamic way to manage staff. The system allows documents and communications to be shared and managed across multiple tiers of stakeholders. Intelligent meta-tagging allows data to be collected through formal and informal channels and mined. These tools ensure correctness, completeness and timeliness of data.

While this is still not independently validated data, it is a huge start in cohesive thinking. Civic tech enables the Mission to bring offline data and processes into the digital domain.

Government-to-citizens monitoring: Delivery of services directly to citizens has gathered force in India through the combined impetus provided by Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, and mobile phone penetration (JAM), easing the launch of initiatives such as Direct Benefits Transfer, and BHIM and the Unified Mobile Application for New-age Governance (UMANG) apps. Gathering the voice of citizens can help design better solutions, and deliver better implementation. Latin American countries have pioneered processes in participatory budgeting, which allows citizens to participate in the decision-making process for allocating local budgets to different initiatives and plans, and citizen oversight mechanisms, to gather feedback or complaints and to form local auditing committees. Such initiatives can augment and speed up third-party verification programmes. Citizen participation can be used to improve accountability and governance of public institutions. For governments, despite best intentions, have not been able to transform the lives of citizens, due to corruption, inefficiencies, hidden interconnected agendas, and weak political states.

Technology offers new ways to involve the public in last mile tracking. Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) is using IOT and tech solutions to collect citizen feedback to monitor the quality of public toilet cleanliness. This independent audit lens helps cities track third-party service providers and improve service. Access to clean public toilets enables the goal of open defecation free cities. E-awareness initiatives, such as online courses on sanitation management, can be used to shape behaviours. Vehicle tracking solutions have been deployed in many cities to monitor waste collection and truck route optimisation. Biometric mobile attendance apps track field sanitation staff. The challenge in governance is always lack of resources and staff. Civic tech enables cities to identify the hot spots and patterns, and thus respond dynamically and better use constrained resources.

Leveraging data for governance monitoring and impact assessment

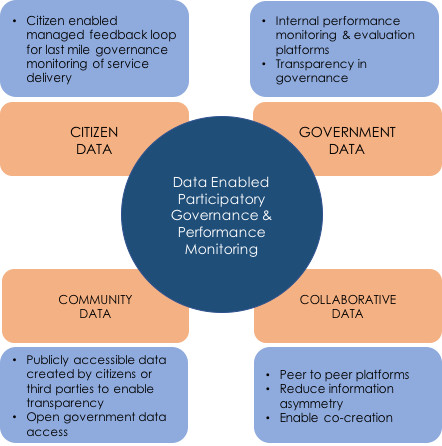

Measurement is the key to success of any initiative. Impact assessment has typically been done through last mile sampling, face to face interviews, and multi-parameter qualitative and quantitative assessments. Technology allows data to be captured in real time from multiple sources and multiple formats. This improves volume and velocity of data gathering. Technology allows improved collation, analysis, and reporting to enable transparency.

Government data: Government data is difficult and slow to source. Data becomes obsolete by the time it is collected. ICT and IOT-based solutions allow dynamic data capture from states, cities, and urban local bodies. Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) SBMPedia uses a highly indexed methodology for user categorisation and fast retrieval of data. Earlier, official reports from cities or states had to be collated. Each delay required redoing the national report. Today, the automated engine allows cities to submit data in different formats. Big data analytics, rapid visualisation and reporting create dynamic performance score cards. Missing data is easily identifiable, and the shared platform creates urgency in all stakeholders to meet deadlines.

Collaborative data: Government information exists in silos and informal channels. SBMChat is a peer-to-peer information sharing tool that mimics social media. Data, images, messages, and documents are being shared by officials from different cities, states or clusters. Tiered access allows external experts to contribute to discussions on specific projects. Cities compete to show progress. Data can be collected from source in new ways. Smart Cities are looking at sensor-based data capture on location and volume of waste collection.

Citizen data: Citizen experience is the real measure of the quality of public service delivery. Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) has adopted digital, social, and IOT technologies to monitor operations and maintenance. Direct feedback—for example, by using capturing location-based citizen sentiment—improves transparency, and enables rapid response and systemic change.

Community data: Government data has typically been tightly controlled. Quality of data collection is critical for accurate longitudinal and comparative statistics. As citizens become open to civic participation and telecom becomes ubiquitous, communities and private organisations can access open information to build new solutions.

Benefits of technology-aided participatory governance & performance monitoring

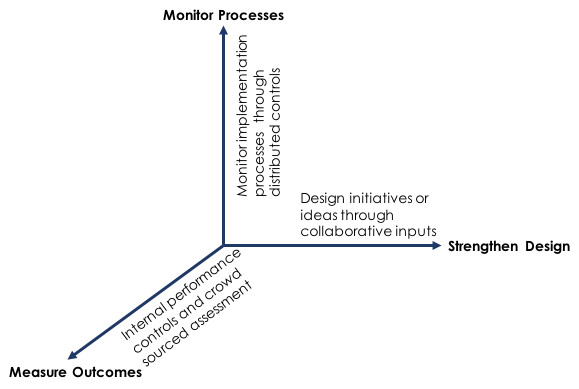

Technology makes it easy for multiple stakeholders and actors to participate in managing transformation. It can be used to embed dialogue, support innovation, and enable process or operations-level contribution.

Strengthen design: ICT tools and widgets enable tiered access and cluster based communication. Policy and initiative design discussion is not restricted to meeting rooms. Collaboration tools allow directors and officials to engage with external subject matter experts on projects. SBMChat, mentioned earlier, allows ideas to be contributed. Strong meta-tagging makes it easy to mine the ideas repositories. This enables a continuous exchange of ideas, knowledge sharing, consensus building, and decision making.

Monitor processes: Real time data rolls up into the common national database. Sensor generated and “user-generated” IOT data streams provide information not captured previously. Missing information is highlighted. Data collection time and people needed to manage data analysis and reporting has been significantly reduced. Data-driven rules can create alerts and escalations, in turn improving coordination between field staff and officials. This has led to an increase in accountability.

Measure outcomes: Cloud-based analytics engine uses real time and historical information to build automated dynamic dashboards. Outcomes can be easily visualised and patterns can be mapped. Simple and complex KPIs can be tracked. This has improved real time visibility into status and performance at central, state, city, and local levels.

Challenges for the future of technology-aided participatory governance & performance monitoring

The current government is emphasising performance monitoring and evaluation for missions, ministries and programmes. The enthusiastic uptake of tech-enabled monitoring by Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) is a start. But any mission or ministry needs to institutionalise the use of civic tech for sustained governance improvement. The factors outlined below can be points of failure and must be mitigated.

Belief in change: Faced with a humongous challenge, it is easy—even for those entrusted with the mandate of change—to lose motivation. Change management needs to run top-down as well as bottom-up, with each person believing that true change is possible—and not get distracted by temporary solutions or cosmetic, media-targeted initiatives.

Support for innovation: India has a 70-year history of managing governance in a specific way. Many processes were inherited from the pre-independence era. Innovation requires imagination. Ideas may come from internal and external sources, but bureaucrats must envision the transformation that’s possible with civic tech, and believe that transparency can provide real short-term and long-term benefits, and create intangible returns on investment.

Continuation of stewardship: New ideas need committed support and time till they become ingrained as new habits. However, as custodians of initiatives are shuffled or transferred, there will be a need for systemic stewardship. Ideas will need to be retained even when leaders and officers change. Else, progress made will be lost.

Sustained commitment: Strong initial championship creates a positive momentum for all stakeholders to eagerly adopt new ideas and new tech solutions. But initiatives run over several years. Managing operations is a day to day, year to year task. Commitment must be sustained at every level within the organisation to use civic tech on an ongoing basis, and to maintain and upgrade it for continued benefits.

Improved communication: The mission will operate through a diffused spread of staff, contractors, officials, and non-profit or self-help groups. There needs to be initial and continued capacity building to enable all stakeholders to use the new solutions, manage information and communication, and accrue benefits.

Shared transparent benefits: Real time information can bring transparency, reduce inefficiencies, and improve performance focus of the mission. True benefits occur not from installing a solution, but from ingraining it into the workings and habits of the organisation. However, transparency also hampers vested interests and dampens existing low-efficiency practices. Hence, some individuals or groups may not be aligned to data-driven action and decisions. Ongoing stakeholder management will be critical to line up commitment, align organisational and national interests, and subvert or penalise special interest groups.

Citizen engagement: Many civic tech solutions rely on citizens to change behaviours, participate in the governance process, or leverage open data sources to create new solutions. Information dissemination, dialogues, and continuous engagement is needed to improve citizen awareness and participation.

Ownership of change: Cleanliness is a challenge that can never be overcome without the active, eager, determined, and supportive behaviour of citizens. After all, more and more waste is generated daily, age old habits of low consumption and reuse are being lost, and infrastructure, even when provided is often vandalised, misused, or not used. Archaic beliefs, superstitions around cleanliness and waste, and lack of respect for common goods creates ongoing challenges that neither technology nor greater funding can solve.

Ultimately, technology can provide non-linear and scalable benefits to governance monitoring, but the benefits can only be realised if Swachh Bharat Mission continues to champion data-driven, transparent and participatory modes of decision making, communication, management, and status monitoring. This will require changes in behaviour, goal alignment, and commitment at every level—from leadership to local staff.

Waste management: Fixing the links in the chain

Over 2015-16, the focus was on building public/community toilets, and household toilets. Over 2016-17, the focus shifted to the daily challenge of maintaining cleanliness across the entire waste chain—from segregation to collection to disposal and recycling. Segregation at source is expected to be launched as a national drive.

So, what exactly has been achieved?

Funding for infrastructure

-

India’s urban population of 377 million generates 62 million tonnes of waste annually. Only 20% is disposed properly.

Even when cities show improvement in door-to-door collection efficiency, the waste needs to be segregated, treated, disposed, or converted. The entire chain requires investment, innovation, redesign, and alignment.

The waste disposal ecosystem has always been under-invested due to its cost and complexity. At the policy and funding levels, true outcomes have been created in unlocking the ecosystem and creating effective pricing, policies, and linkages to support waste-to-energy and waste-to-compost production. Convergence funding has been mapped under the Smart Cities Mission to bring together funds from Swachh Bharat, AMRUT, and Smart Cities to develop the cleanliness infrastructure.

Converting waste to compost

-

164,891 metric tonnes of compost is produced from waste—a fraction of the estimated demand of 627,000 metric tonnes for bio-fertilizers.

A market development access policy has been instituted to link the value chain. Fertilizer marketing companies are obligated to buy city compost at Rs 1,500 per metric tonne. Cities can also sell directly to farmers at the same rate. India has 43 waste-to-compost plants, but 47 more have been commissioned. Initiatives are underway to increase segregated composting in cities, which will require citizen partnership, and building more composting plants.

Converting waste to energy

-

88.4 megawatt (MW) energy is produced from waste—a fraction of the 330,000 MW annual energy installed production capacity.

Central Pollution Control Board reported that by 2014, of the 144,165 tonnes per day (TPD) of waste generated across all states, 115,742 TPD was collected and 32,871 TPD was treated. Total 76 waste-to-energy projects were established, of which 41 were biogas plants.

The Union cabinet has approved a proposal from the power ministry to mandate all state power distribution companies to purchase power generated from municipal solid waste at a sustainable rate. The tarriff policy has been amended, which will enable viability of waste-to-energy plants.

The actual technology and process of waste-to-energy production will need to be determined by each city—keeping in mind the calorific value of waste content and quantum of daily usable waste collection. Aggregation and pooling mechanisms may need to be considered. Most smart cities are analysing municipal solid waste management options.

Easing the value chain for solid waste management will, in turn, enable micro-entrepreneurs and large firms to invest in waste management segment, thus expected to unlock end-to-end longer term impact.