[By David.Monniaux (Own work) (CC BY-SA 3.0) or (GFDL), via Wikimedia Commons]

It’s Diwali night here in Mumbai as the final touches on this piece are being put out for my editors to pore over. I’m missing on the fun. But the overwhelming emotion is one of joy and relief as my little girls—whom I fondly call Puchu and Champu—are out celebrating the festival. Don’t ask me how and why I thought those names up for these girls of mine. The missus still hasn’t forgiven me and the girls look traumatised when I call them that when their friends are around.

Be that as it may, my joy comes from having spent the morning answering questions from Champu, now a senior in kindergarten. And the relief comes after having pored over the pages of Deep Thinking, the lovely new book by the legendary chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov that was published earlier this year. I followed it up by listening to him engage in a conversation.

My joy and relief come from the fact that, embedded in the pages of his book and the words articulated in his talk, is a compelling assurance: that all predictions about Puchu and Champu’s future, mine included, is dystopian, and ought to be dismissed because it is too pessimistic. Not for anything else, but because it resides on the back of a theory called technological singularity. This assertion may be both ridiculous and monochromatic at once.

Singularity is the hypothesis that progress in technology will trigger changes in civilization of the kind we cannot imagine. And when extrapolated into the future, it imagines a world where humans like my daughters Puchu and Champu become redundant because algorithms will eventually be better at whatever they can do. There is a school of thought that has always believed this future is an exaggerated one.

But much of it was challenged again last week, when it was established that singularity is in the here and now after Nature magazine published a paper about an algorithm called AlphaGo received a major upgrade and can now learn tabula rasa (from a clean slate). Simply put, without any human intervention. That algorithms of this kind are now possible and the implications of it all on the future of little girls, mine included, had me stunned.

It was purely incidental that I was reading Kasparov’s book. It contains his thoughts on artificial intelligence, backed by his experience in dealing with the beast on the chessboard. While the book offers much fodder for aficionados of the game, it also lends insight into what it means to be human.

Back to my little girls. Early one morning, Champu insisted I spend time with her to explain what a skeleton is. Does she have one? If she does, why is it necessary she have one? Why is it that she doesn’t have a tail? She was most perturbed by the fact that the dog in the neighbourhood we live in, which she dotes on, has a tail—but she doesn’t.

The questions were fast and furious and I had a fun time attempting to answer them. Some of her questions, I admit, had me stumped. The one on why she doesn’t have a tail was a tough one to answer. I did my best to explain, in baby language, the theory of evolution.

So, I told Champu that she and her older sister Puchu, who was fast asleep then, both had great-great-great-great-great grandparents who were big monkeys. Over time, though, these monkeys—aka our ancestors—thought it only appropriate they learn to walk straight. When all of them eventually started to walk straight, their tails would come in the way and they’d often trip and fall. So, over time, their bodies stopped producing tails. That is why her parents—my wife and I—didn’t get a tail. So, she didn’t inherit it either. I thought that answer would suffice for the moment and satiate her curiosity.

On the contrary, she looked closely at her sleeping sister’s posterior, examined mine with much curiosity, and tried to turn her neck that she may peer over her backside to check if there exists any trace of a tail. I then told her that her skeleton has a “tail bone” and one of these days I’ll take her to the college I graduated from to show her a real skeleton, so that she can examine the place where her tail fell from.

Her eyes widened. For a moment, I thought it was delight at the possibility of getting to see a real skeleton. But I was wrong. Turns out, her look was one of distress. Some sobbing later, she told me she was agonised by the “loss” of her tail. If she had one, she reasoned with me, the dog she dotes on may have liked her more than it does now, because they may have had more in common—like a tail.

As is her wont now and when afflicted, her instinct suggested she pick up my phone—an iPhone with Siri, that voice recognition software embedded into all devices created by Apple. The software allows a user to pick a name that Siri may address them by. I’d set my phone to address any user who may use it as “Puchu and Champu’s dada”.

“Siri, where is my tail?” she asked, in her distressed tone.

“Here is what I found, Puchu and Champu’s dada,” Siri answered nonchalantly.

The screen popped with links to songs on YouTube like Did you ever see my tail?, Where is my tail?, Did you see my tail too? and so on.

On the one hand, there was some amusement as I watched the innocent spectacle play out. On the other, it triggered a series of questions. What kind of a future am I staring at? It wasn’t too long ago, or at least it seems that way, when my dad would read out fantastical stories to my brother and me—some plucked from his imagination, and others from now-forgotten titles like Amar Chitra Katha and Chandamama. But there was no taking away from the fact that, for the both of us, daddy was the repository of all knowledge.

But when did things start to change? How did voice recognition software embedded into the now-ubiquitous tools that permeate our lives and built by entities like Apple, Google, Amazon and Microsoft creep insidiously into my life? Do they pose a threat to a father emotionally bonded to his daughters? Is it possible they may replace him? Why else did Champu engage Siri when distressed and not turn to me for solace instead? Had the world gotten too big? Were my answers insufficient for her inquisitive mind?

But then, sobriety started to come in from the unlikeliest of places—a conversation that Kasparov quotes in his book between Deep Thought, the most powerful computer ever created, and its creators in the sci-fi classic A Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams.

“All right,” said Deep Thought. “The Answer to the Great Question …”

“Yes …!”

“Of Life, the Universe and Everything …” said Deep Thought.

“Yes …!”

“Is …” said Deep Thought, and paused.

“Yes …!”

“Is …”

“Yes …!!! …?”

“Forty-two,” said Deep Thought, with infinite majesty and calm.

“Forty-two!” yelled Loonquawl. “Is that all you’ve got to show for seven and a half million years’ work?”

“I checked it very thoroughly,” said the computer, “and that quite definitely is the answer. I think the problem, to be quite honest with you, is that you’ve never actually known what the question is.”

Kasparov thought it both funny and profound at once because, to his mind, this conversation highlights a distinction that we often ignore and has repeatedly been made by Picasso: “Computers are useless. They can only give you answers.”

To Kasparov’s mind, “An answer means an end, a full stop, and to Picasso there was never an end, only new questions to explore. Computers are excellent tools for producing answers, but they don’t know how to ask questions, at least not in the sense humans do.”

If I were to hold that thought for a moment and go back to my little girl, by that yardstick, the intelligence embedded in her is infinitely superior to that built into the most powerful machine. Because Champu was born with a curious brain and a beautiful mind that compels her to look at the world with much wonder and ask questions like why did her tail drop off? Can brute computing and artificial intelligence do that?

Recent developments suggest we are close to the Holy Grail. But Kasparov takes note of that, places another subtlety on the table and explains what it takes to ask a question. To do that, he quotes Dave Ferrucci, a pioneer who first started his work at IBM to build the super computer called Watson. He was then lured by the hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, headed by the quirky Ray Dalio, to start work on creating algorithms that can predict what way the markets may move. “Computers do know how to ask questions. They just don’t know which ones are important.”

This, to my mind, raises another question. What is an important question? It is a question that has researchers at the frontiers occupied as well. And they have made significant advances there.

“This is one reason why there is such a push now in social robotics, one of the terms used for studying how people interact with artificially intelligent technology. How our robots look, sound, and behave is a big part of how we choose to use them,” explains Kasparov.

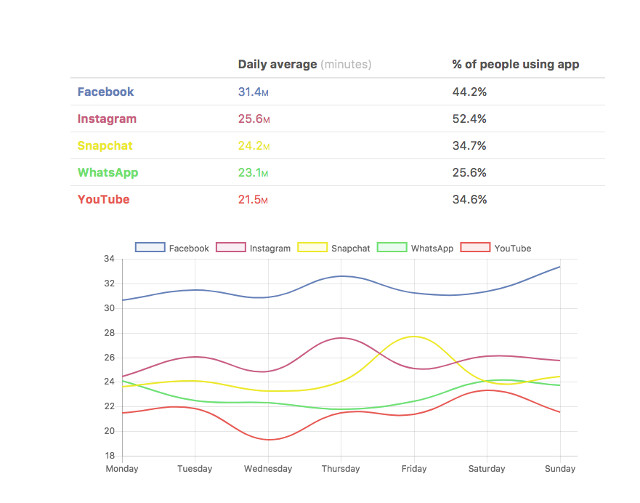

When looked at from that perspective, it is inevitable then that the finest minds in computing are at work to ensure my little girls are glued to their platforms. That their work is paying off is evident from the data I am sitting on right now for the week ending September 25, 2017, which comes via an app I use, called Moment.

These numbers are the global average of the number of minutes people spend on devices staring at Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, WhatsApp and YouTube for the week ending September 25, 2017. Very simply put, people, without realising it, spend a little over two hours doing nothing “productive”. I mean, what do you really do on social networking tools like Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp? Let’s get real about this.

But for better or worse, this is what it is. My girls are pitted against the might of raw computing prowess and the world’s finest minds to wean them away from me. So, what are the odds that I may have their attention?

To understand this, it is pertinent to go back to Kasparov’s story. There is this part that has been reported widely and when read in isolation, sounds dystopian: that he lost to Deep Blue. But when looked at from his eyes and with the benefit of hindsight, we now know IBM’s Deep Blue won because the rules were broken. And Lou Gerstner who was then the CEO of IBM could see much merit in putting his muscle and some money that in the company’s scheme of things was chump change. What panned out was a game that was not played fair and square. How it all turned out makes for a riveting read.

But that said, he also concedes that if all things stayed equal, he may have stood his ground for another three to five years on the outside before artificial intelligence and the brute force beat him fair and square. He was prescient and we now know even the reigning world champion is no match for Artificial Intelligence engines like Google’s AlphaGo. After all, machines don’t tire out, aren’t prone to emotional vulnerabilities, and can go on and on—unlike him, my Puchu and Champu, or any other human.

But if Kasparov is to be believed, my little girls’ chances of bonding with me are superior to anything artificial intelligence can think up. By way of example, he writes in his book, “The simple sentence ‘the chicken is too hot to eat’ can mean that a barnyard animal is ill or that dinner needs to cool down. There is no chance of a human mistaking the speaker’s meaning despite the inherent ambiguity of the sentence itself. The context in which someone would say this would make the meaning obvious.”

Added to this is another fact he talked about in his interview: humans feel emotion and can empathise in just the right way. So, when my little girl looked troubled at Siri’s inability to answer appropriately whether she indeed had a tail or not, “You are a dirty Siri,” she said in exasperation.

“That’s what I reckoned,” the voice answered.

The response made her cry even louder. The sleeping Puchu woke up and kicked her for creating a ruckus. It prompted Champu to cry louder. Before cradling her in my arms, I raised the phone and commanded Siri to come to life.

“Hey Siri.”

“What may I do for you?”

“Give me a hug.”

“That may be beyond my abilities at the moment,” was Siri’s prompt response.

I smiled. My job was not going anywhere. I picked my little girl up, hugged her, and both of us made our way to get a little something to make us happy; maybe locate her dog and find out when her tail went missing.

(This is a slightly modified version of an article that was first published in Livemint.)