[By Krzysztof Kamil under Creative Commons]

If things seem under control, you are just not going fast enough - Mario Andretti

Imagine you had to punt on Facebook, Google, Amazon and WeChat. Where would you put your monies? On the face of it, Facebook has over 2 billion monthly users who log in billions of hours engaged with the platform. Ditto for Google. These look tempting.

As opposed to that Amazon has just about 300 million-odd users on its platform. Not much to write home about. Then there is Apple. While there is no taking away from the fact that it has an iconic status, it was under the steely gaze of Steve Jobs. Many have it that the entity looks jaded now.

As for WeChat, while it has an impressive 900 million-plus users, all of them are restricted to China—an unknown geography to investors outside the metaphorical Great Wall that surrounds it.

At least in theory then, Facebook and Google ought to be the frontrunners for your money. And why not? With scale of this kind, pretty much every entity would want to reach out to the audiences on Facebook and Google. And to do that, they advertise. The bulk of the earnings of both companies come from these advertising dollars.

But what if we were to look at it differently?

Despite having 2 billion users, Facebook clocks $28 billion in revenues. Simply put, it earns only $1.6 each month out of every user. It’s much the same with Google. Does that imply these are terribly inefficient entities? And is the reason they are doing well only because of the scale at which they can engage with people?

Then there is evidence that clearly indicates conversion from internet ads to purchases falls in the low single digits. Add to this an impending sword called ad blockers doing the rounds. It is finding its way into legislation in many parts of the world. Is it possible then the business models of Facebook and Google are under threat?

As opposed to that, Amazon is built to get a job done. Bluntly put, it opens the door to get a transaction done. It does not ask me to reach to what someone puts out like Facebook does, or redirect me to someplace else like Google. Instead, it goads me on until I buy something. It is at work to integrate into my life. And the only way it can do that better is if every transaction on Amazon becomes easier and cheaper until it becomes “irreplaceable”.

Much the same thing can be said about Apple. It has built a cult-like ecosystem that marries its near perfect hardware and not-so-near-perfect software. But it is hard at work to blur the lines between both. And eventually between the consumer and the device.

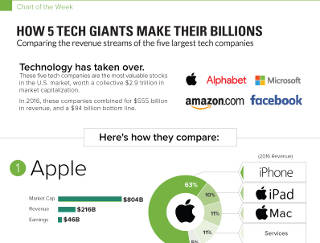

[How the 5 Tech Giants Make Their Money. Click or tap on the chart to view it. Source: www.visualcapitalist.com]

Is it possible then to imagine a future where I live in a world Amazon or Apple design? Is it possible that Facebook and Google may be also-rans?

The battle brewing between the tech giants has the power to reshape every market and industry—and indeed our lives

The battle brewing between the tech giants has the power to reshape every market and industry—and indeed our lives. For example, if and when Apple switches on a tiny payment feature on its phone, creating a virtual credit card, it will instantly have 600 million users. A base larger than what the top 10 credit card companies have built over decades. All gone in an instant. The threat to retailers and bankers is here and now. But they are not the only ones. Technology-driven startups are waiting on the side-lines of every market. Waiting to destroy and create a new paradigm, a new set of rules with which to do business.

Rewriting the Rules

In the past few years, technology companies have come to dominate the ranks of the 10 biggest firms by turning accepted wisdom on its head.

Over the last century, two economic concepts have ruled the basis of business strategy and how firms thought about expanding their moats.

1. Economies of Scale: As size of operations and output goes up, cost per unit comes down. Because fixed costs are spread out over more units of output. This saving drives up profits.

2. Economies of Scope: Simply put, when firms diversify into a complimentary range of products, this too gives it a cost advantage, as it is able to use its capabilities and assets more efficiently. These capabilities include intangibles like brand building and distribution. So, if I am a player who has achieved Economies of Scale in the soap business, I may as well sell shampoos, toothpastes, detergents, shaving systems and even batteries.

Modern empires—the largest global companies—were built on this wisdom.

Moored in these two concepts, firms created competitive advantage and what they believed were unassailable moats. Even today, managers take day-to-day decisions based on these axioms.

They are wrong.

Technology nullifies these moats.

Consumer internet businesses have natural economies of scale and scope. It is part of their DNA to use the innate power of the internet to achieve near instant scale. And when you pour some rocket fuel (read venture capital) into the mix, it can catapult a business into serving millions of consumers quickly. Bundling in an adjacent offering (read: scope) is as easy as programming in a few pixels. Venture capitalists (VCs) look for product - market fit. Once that’s proven on a small base of users, it is assumed that infusing a disproportionate amount of capital will dislodge market structures. It’s proving to be true.

The cost of reaching a consumer over a smartphone is near-zero

The cost of reaching a consumer over a smartphone is near-zero. With network effects a business can drive it down to negative zone—consumers invite their peers and the platform grows on its own. Example: WhatsApp, with a staff of 35, grew to near 600 million users in just four years. Its revenues were about $10 million when it was acquired by Facebook for a mind-boggling $22 billion. Today, it is used by 1.2 billion people a month. WhatsApp single-handedly destroyed the SMS revenues of many telcos around the world, especially in India.

The Achilles Heel

Proctor & Gamble (P&G), the soap company I mentioned earlier, is a $80 billion monolith. It now sells 40 billion units of consumer products a year to 4 billion people—that’s almost the entire adult population of the globe. Yet, it enjoys no direct relationship with them.

You can apply this lens to pretty much any traditional firm, which built a stranglehold over what they thought were strategic assets—production and distribution. They used their bargaining power to build humongous physical brands and networks. However, they have little by way of contact with their end customer. And therein lies the rub—it takes little to disintermediate them, and startups are attacking this weakness.

It’s happening every single day, in every sector.

Incumbents cannot cope with the brutal speed and explosive nature of the attack on their “old-world” business models. Their own scale and scope sometimes act like deadweight, and they fail to adapt to the speed and agility the technology-lubricated jungle now demands.

This creates a paradox: While companies are growing faster and bigger, they are dying as well. More than half the companies on the Fortune 500 list have vanished since 2000.

Take the legendary war between Walmart and Amazon. Even though Walmart has brand legacy and scale of megalithic proportions, its relationship with customers is thin. A loyalty programme is the only layer through which it conducts its customer relationships.

Amazon on the other hand, enjoys a deep relationship with its customers. It knows exactly what they buy, when they buy and what they are willing to pay. It has created a plethora of services to wrap around its users: Prime, Prime Video, Amazon Dash, Amazon Go, Alexa among others. All designed to increase the depth of engagement with a customers’ life.

[The Bezos Empire. Click or tap on the chart to view it. Source: www.visualcapitalist.com]

This focus on the customer has spawned an “optionality”, far in excess of what any traditional business can imagine. Amazon uses data to weave itself into the life of its consumers and is re-writing the book on how to build a company.

So, if you think Walmart is competing with Amazon for share of the consumer’s retail spend, you’re right. But if you think the folks at Amazon are competing with Walmart, you’re wrong. Amazon is designing a new lifestyle for its customers.

The New Moat

Engagement with the consumer is becoming the new moat. Amazon is not playing with Economies of Scale and Scope. It fights with a third weapon, which I call Economies of Engagement. These are the hooks they create to keep us addicted.

The market can see that. Despite being about 4 times the size of Amazon, and making more money in a year than Amazon has made in its entire 21-year existence Walmart commands only half the marketcap of Amazon.

Similarly, when Amazon buys Whole Foods, it’s the power of engagement at play—that confers upon Amazon the unique ability to seamlessly ”transfer” its customers from the online world to the offline. The Whole Foods acquisition is not simply an online retailer dabbling in offline. That has been done and dusted—Alibaba has been acquiring offline retailers for over a decade with not much to show for it.

Control of the relationship with the consumer is more valuable than the underlying transaction

When looked at from an engagement framework, the job isn’t about going offline and opening a store. The job is to nudge customers to visit it. If they are already engaged online, the store becomes a force multiplier. It allows Amazon to funnel customers seamlessly between the offline and online worlds. The offline store is now a connected, living, adapting, physically accessible point for your consumers. What’s becoming increasingly clear to every CEO: control of the relationship with the consumer is more valuable than the underlying transaction.

Some incumbents do realise this and are gearing up.

Unilever paid a billion dollars to acquire Dollar Shave Club (a direct to consumer, technology driven shaving products company). The fact that Dollar Shave Club knows its customers and has the power to engage them is the wedge that Unilever can drive into the towering 70% market share that Gillette (a P&G company) enjoys. It compelled Gillette to announce it will shave up to 20% off prices to take on Dollar Shave Club and its peers. Clearly, Gillette, is under siege.

Inside Economies of Engagement

Last week, when I had gotten Behind the Global Tech Investing Tsunami, I had delved into why technology companies are valued differently from traditional firms. Investors presume traditional firms that have moats made of scale and scope will always come under attack. But when it comes to tech firms, they bet on their ability to expand the moats that surround them.

There is a new kind of economics at work here. The only ones who can dabble in it are firms embedded in technology. It gives each of them an advantage—the ability to get into any business they choose. That is why they have grown as fast as they have. But it also means they have to compete fiercely with each other.

The issue now staring at these firms is, how not to get pipped by tech firms as nimble as they are

The issue now staring at these firms is not about how to upend traditional businesses, but about how not to get pipped by tech firms as nimble as they are. And to address that they must answer a fundamental question: I got millions of people on the network I built. What can I now do to keep them here?

These firms live in constant fear of becoming irrelevant. They are jostling with each other to hold users’ attention. The outcomes are uncertain. To get the import of that, spend a few moments on these mind numbing figures:

- The Facebook network owns WhatsApp (1.2 billion users), Facebook Messenger (1.2 billion), and Instagram (700 million). This is besides the 2 billion direct Facebook users.

- Google has seven services with over a billion monthly active users, besides the 2 billion active devices on Android.

- YouTube delivers a billion hours of video a day.

- Apple has more than a billion active devices.

- Microsoft claims 1.2 billion people use its office products.

The scale at which these companies engage consumers is staggering. The average American spends five hours a day on his mobile device. I suspect the number is even higher for the consuming classes of Chinese and Indians because a smartphone is their connection to the world.

There is very little in common between these tech firms except that billions of people use them every day. Each visit, view, click or buy people make on their platform leaves behind a trace. Their job is to collect these traces because embedded in it is some value. What do I mean by that? A few things actually.

Let’s take Amazon as a case in point and see how it creates an economy of engagement.

1. A mindset of abundance

“Cut fixed costs, make them variable.” So goes the mantra in every boardroom.

Traditional companies look to reduce average cost by cutting down on fixed costs and make them variable so that they can be responsive to changes in demand. But tech firms don’t worry about their ability to create demand—their deep connections with customers allows them to scale and control demand.

Economies of Scale and Scope in this world are subservient to the Economics of Engagement

Instead, they invest to fit new services into their ring of engagement to bind their customers. For them fixed costs and infrastructure are a way to create possibilities and a deeper, wider moat. So what you hear instead are reports of staggering investments into infrastructure and research and development.

Economies of Scale and Scope in this world are subservient to the Economics of Engagement.

Amazon knows exactly how to motivate users to visit the neighbourhood Amazon Go or Whole Foods store based on data. It can make accurate assessments and curate demand—something that Whole Foods, as a stand-alone business, never could.

2. I feed the platform and then it feeds on me

The trade they make with consumers is not about what they sell, but what data they can gather about their habits. The consumer thinks the services are free, but they are paying through information about their behaviour.

The tech firms study behaviour. Having done that, they try and mould their offerings until they fit a consumer like a second skin.

For example, Amazon Prime is a loyalty programme where you pay to get yourself locked in. The Rs 499 you pay for the service does not make a dent in the financials of Amazon in India where it’s pouring in billions. But your brain tricks you into thinking about the “sunk cost” of that money and keeps you buying from Amazon.

Soon a habit is formed—you will stop checking Flipkart and not even compare prices. Amazon sets up massive fixed infrastructure to serve its Prime customers, and in turn its Prime customers give it so much business, that it makes the fixed investment viable. But forget that. The real collateral benefit is that you would have traded so much data with Amazon that you will find it difficult to switch.

Jeff Bezos went to the extent of saying that not joining Prime would be “irresponsible” on the part of the consumer. "We want Prime to be such a good value, you’d be irresponsible not to be a member,” Bezos wrote in a letter to shareholders. “Prime has become an all-you-can-eat, physical-digital hybrid that members love… There’s a good chance you’re already one of them, but if you’re not—please be responsible—join Prime."

3. Own the choice not the transaction

They don’t want you to message, buy, ride or search. They want you to WhatsApp it, Amazon it, Uber it, Google it, Netflix it.

Amazon knows that the value is not in the transaction to buy. It exists in getting early into the consumers’ purchase process, when they begin to search for a product, are looking up reviews and trying to make up their minds. Thus, the more unbiased and usable content and reviews on its platform, the more people will come to it before they take a decision. A report last year said 55% of online shoppers start their product searches on Amazon, and not on Google.

So, Amazon’s pricing power and stickiness does not come just from its massive assortment of products, but from the fact that it is fast becoming the port of call for product search. It is inevitable then that it becomes the place to go to shop. This gives it a leg up even in the advertising business, as it can deliver an integrated purchase experience versus Google and Facebook.

To squeeze engagement value even more, it is investing heavily in private labels. More than 90% of the batteries sold on Amazon are in-house brands. This proves that consumers are happy to drop age-old brands in favour of a company they engage with daily. By the way, the brand being hurt by Amazon’s private label is Duracell, owned ironically by P&G.

In much the same way, WeChat is an evolved example of economies of engagement. It has nearly a billion Chinese users who use it to do everything from booking classes, to hiring cabs, to investing in mutual funds. It has created a virtual operating system for the consumer: they can operate their lives entirely on WeChat.

This excerpt from a Bloomberg article gives you a sense of the power of the platform and the WeChat lifestyle.

WeChat now has 937.8 million active users, more than a third of whom spend in excess of four hours a day on the service. To put that in context, consider that the average person around the world spends a little more than an hour a day on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and Twitter combined. Tencent’s services are so pervasive in China that startups there find it difficult to refuse forging alliances with or accepting investment dollars from the company. “It’s a little bit like the Godfather Don Corleone saying, ‘I’m going to make you an offer you can’t refuse,” says Andy Mok, founder and president of Beijing-based consultant Red Pagoda Resources LLC. “If you don’t take their money, and they invest in a competitor, it can be deadly.”

A Double-Edged Sword

But. Human attention is a scarce resource. With multiple devices and multiple modes of consuming content, attention is fragmented. And every new device, technology, or app makes the battle for attention fiercer. And expensive.

Then there’s a second challenge: Using the internet or smartphone is taxing for the brain. That’s because the way you use the internet or a smartphone is markedly different from how you consume other electronic media like TV or radio. The latter are “lean back” mediums. They can play in the background. Users can choose to dip into it whenever they want. Watching or listening to them does not impose any demand on your brain.

As opposed to that, the internet and smartphone are “lean in” mediums. To consume from it requires effort. You have to tap or swipe the phone that it may do something. It insists on a response and that drains your attention. They place what neuroscientists call a cognitive load on the brain.

So, users live under the illusion that they have the option to choose. But to choose, they must expend energy by leaning forward. Only after that is done can they “lean back” and let a movie or music stream.

But the brain craves familiarity and control; and you look for shortcuts.

This explains why of the 50-odd apps somebody may have on their devices, on average, 8-10 will account for the most consumption. These are inevitably those that are simple, familiar and offer rewards—like games where points can be scored or social media where every share may elicit a response, the equivalent of a rewarding Dopamine hit.

To make things easier, people take cues from others on where attention ought to be directed. This is how things go viral. Suddenly Game of Thrones gets downloaded a billion times or Pokemon Go reaches 100 million people at a rate unprecedented in history.

These natural limits to our attention create an existential problem for tech firms: their business exists only if a consumer keeps their app alive on their devices. The moment the user’s attention moves to something else, the firm becomes irrelevant.

To that extent, the user’s attention is the only competitive advantage they have. That is why Netflix must understand what movies and television shows each of its users watch and how they choose. This helps it create an interface they feel most comfortable with. In turn, it can then design to create something that brings down the cognitive load.

If it can do that successfully, it has significant implications for the business model.

A typical movie is designed such that 40% of its budget is set aside to attract footfalls into the movie hall. One of the biggest risk factors for a film studio is that while it may create compelling content, it may fail to market it well. The risk gets bigger when it has to spend big money on blockbuster stars to get people into theatres.

However, if Netflix can play the Economies of Engagement game, to can upend the movie studio business. What it means is, embedded into its business model is the potential to drive audiences to watch movies at near negligible costs. A film’s success depends on how good the execution and story is—not the face value of the star cast. So, it can make movies and TV series with probably half the risk of a stand-alone production company.

Once you can dominate the customer’s attention, you can dominate the business

Netflix figured this and created a budget to become the largest production studio in the world. All other factors remaining the same, the probability of Netflix creating a hit show or movie is higher than that of any other studio in the world.

Once you can dominate the customer’s attention, you can dominate the business. And it unleashes new ambitions—as you can read in this piece on Netflix. New ambitions suggest optionalities to the investors—who then go out and are willing to value Netflix at $70 billion, which in turn fuels its ambitions even more.

A similar script plays out for every tech giant. Their engagement fuels optionality, which fuels the money investors are willing to pay for it, which fuels their ambition to create even more engagement and optionality.

This blurring of boundaries is visible everywhere. You find Facebook vying for more video views than YouTube. Then Snapchat emerges as a competitor that both need to watch out for—it can disrupt video by making it part of the conversation. Twitter goes buys the NFL rights—all to stay relevant.

Their aim is to crowd out the other gatherers of your attention. In fact, they are now taking this effort to another level and trying to see if they can be the ONLY gatherers of your attention. And that is taking these tech firms into interesting new directions.

The Battle to be the One and Only

Currently, your attention is available in two forms, text and video—and on a device with a screen.

But the screen is a self-limiting proposition and fighting for every pixel on it is an expensive battle.

Tech firms are asking the question: Can I interact with consumers’ in lean back mode, so that there’s no cognitive load and engagement is so effortless that is becomes a habit?

Can they retreat into the background, become ambient—and simply get the transaction done? Can they make money by anticipating your wishes and becoming the Man Friday who charges you a small fee for every errand it runs? The algorithmic equivalent of Jeeves from PG Wodehouse’s novels, who could solve every problem that his master had, even before he knew he had them.

This push is coming from advertising-driven companies like Facebook and Google. They are faced with a paradox: To make money off your attention, they have to divert your attention to the ads they are peddling. But that is an extremely inefficient way to do business. It forces them to walk a very thin line—they must find a way to take so little of the value from the consumers’ attention that their interruption doesn’t break the connection.

The billions they make by serving you ads is under threat, as consumers are very good at ignoring ads. They are discovering that “lean forward” attention is extremely expensive. People in lean forward mode want to do exactly what they set out to do and leave. The advertising-driven model is not sustainable, especially with new players threatening to create ad-free, intelligent messenger-bots that get the job done versus show you an ad around it.

I Don’t Have to Watch the Device, It Watches Me

So, the intent is to make technology invisible and intelligent at the same time. Instead of you paying attention to the device (which is “expensive” on your cognitive senses), the machine pays attention to you, interprets what you need accurately and makes it available.

And that’s why artificial intelligence (AI) has made a comeback from out of our labs.

But how do I serve you instantly, perfectly, all the time? That puts another bar—understanding your context, to know what you normally do before and after you make a choice. That way I can anticipate. The aim is to have your AI-backed voice-and-gesture activated assistant understand what you need before you ask for it. It shouldn’t make you listen to an endless menu of options. (Imagine leaning forward to strain and hear and then recall the options your voice assistant is suggesting—that will truly be “lean forward”!)

To make computing ambient, the information they mine is more and more intimate. They are going beyond the screen to the phone to the watch and then to the environment in your home and car. They will be the ones who will deploy devices in your home (check out Homecenter by Apple or Alexa by Amazon).

They can know precisely what you could be looking for, since they are now tracking your life versus your eyeballs. Devices around us (in our home, car, or office) will try and anticipate our needs. This is not as complicated as it sounds: while our needs appear unique to us, we are similar in more ways than we can imagine. We are creatures of habit and mimic other people’s lives. (Quick clue: the reason Nike shoes or an Under Armour t-shirt appeal to millions.) So, data can usually help the machine learning algorithm predict what we want and push us towards suitable products.

They are marching inexorably towards dominating your attention. And the sweet spot for them is when they become an invisible part of your life.

That’s the battle these tech giants are fighting. The one that can dominate your lifestyle will be the winner. That will give rise to the trillion dollar corporations. For whom there will be no boundary.

The contours of this thinking are already visible from the plans of the top 10 tech companies: They will make cars, fly drones, sell in stores, help you navigate, deliver food to your home, play music for you, recommend a film, keep you fit, check your health. There is no part of your life they don’t want a piece of.

Google, Tesla, Apple and Uber are vying to become car companies. Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Apple and YouTube are vying to become your entertainment destination. Netflix says the only competitor it has is sleep—not Amazon, HBO, or Apple. Facebook wants to own news, create a virtual reality ecosystem, launches a messenger bot to help you interact with businesses and shop online. The list goes on.

Amazon’s vision is the most ambitious: to embed its voice services in every possible home, thereby reducing the importance of the device, OS, and application layers (it’s no coincidence that those are also the layers in which Amazon is the weakest).

To own your attention is the Holy Grail. Ambient and invisible computing is the means to do it. That’s the reason all the players are betting big on voice and AI (Alibaba announced a new voice device as I was writing this piece).

Consumers want only three things—products, services and experience. The firm that can stitch all three into its Jeeves, will eventually dominate.

In all likelihood, the winner will be a grand total of one. Because your family, your house-help, and even your dog will finally want to choose and spend their attention training only one. And that firm will run your life, even while you live under the impression that you command it.

Wait, but what about…

1. Will it make more of a device junkie out of all of us?

My guess is, no. I see the world moving from a mobile-first to an AI-first world. The concept of the “device” will fade. Instead, we’ll have an intelligent “assistant”—whatever shape it takes—that will help us get stuff done faster, without intruding on our attention. Don’t be surprised that the week you miss gym, your “assistant” stocks up Diet Coke instead of the regular kind.

2. Are there downsides to the way the digital economy is evolving?

Yes, there are. People are becoming aware of the dark side of algorithms pushing videos, articles, ideas, and products based on what we “like”. Like prank videos? The algorithm will dish out an endless stream. The trouble is, it can’t distinguish between a prank video and a hate video. It is optimised for engagement, not for fairness or accuracy. The sole aim of Facebook’s algorithm, for example, is to make us linger and click on an ad.

Also, by choosing for us, it is becoming a gatekeeper for how we spend our time and money, and even who we choose as our influencers. The algorithm picks up on our biases and amplifies them, using data on our preferences to create an echo chamber, which only deepens our biases since we end up viewing more events confirming them. The extreme and deviant behaviour we see on social media is a result of this “optimisation of engagement” and is now trickling into real life. The US Presidential elections and the subsequent fracas over fake news and social media trolling are just the tip of the iceberg.

3. What about the incumbents? Is it already a lost game for them?

Not necessarily. I say this for two reasons.

One, if a firm can deliver a strong experience and demonstrate a strong reason for existing, the tech firms will find it hard to dislodge it. Case in point: the apparel giant Zara, which has used speed to market, and freshness in the store as a compelling reason for women to get addicted to the “experience” of a Zara store. Zara continues to thrive despite the tech firms’ unfair advantage.

So, either you are a strong franchise—and you start using technology to build bridges with customers—or you give in and become a supplier who leverages the power of these networks. Being in the middle is tough. They need to learn to turn the guns on the tech firms commoditising them by embracing clever use of access that technology provides. It’s hard and it will requires them to reframe their business, take hard calls like Unilever did when it paid a huge valuation for Dollar Shave Club.

The second reason this is not a lost a game is, regulators are beginning to act against the restrictive power tech firms exercise.

Facebook and Google survive on making tiny fractions of money each time you leave a trail on the web. They sell your data to each other via the 4,000-odd ad-tech companies, and they blow up millions of pages of advertising inventory in the hope that people will click. The click rate is abysmally low and it comes up with cleverer algorithms to profit off your attention.

Scores of companies have died in the wake of algorithm changes at both Google and Facebook. Since the customer is just a click away from making another choice, regulators have so far believed that these methods are not restrictive behaviour. But that does not take into account the engagement lock-in that brings in the restrictive power.

All that is changing, albeit slowly. The first slap on the wrist came when EU regulators fined Google $2.3 billion for abusing competition laws. This anti-competitive behaviour will play out in sector after sector and the implications are far-reaching. At some point soon, governments will have to sit up and take notice, and safeguard their citizens.