[Waymo's autonomously driven Jaguar I-PACE electric SUV. Source: Waymo]

Good morning,

Most narratives in the mainstream have it that in the mid- to long-term future, fewer people will be needed as work gets automated. But this narrative is flawed, argue David Autor, David Mindell and Elisabeth Reyonlds in The Work of the Future. If anything, more people will be needed. But work must be reimagined. The issue they flag off is, are people in positions of power doing enough of that? Consider developments in the autonomous vehicles (AVs) space for instance.

“AVs, whether cars, trucks, or buses, combine the industrial heritage of Detroit and the millennial optimism and disruption of Silicon Valley with a DARPA-inspired military vision of unmanned weapons. Truck drivers, bus drivers, taxi drivers, auto mechanics, and insurance adjusters are but a few of the workers expected to be displaced or complemented. This transformation will come in conjunction with a shift toward full electric technology, which would also eliminate some jobs while creating others. Electric cars require fewer parts than conventional cars, for instance, and the shift to electric vehicles will reduce work supplying motors, transmissions, fuel injection systems, pollution control systems, and the like. This change too will create new demands, such as for large-scale battery production (that said, the power-hungry sensors and computing of AVs will at least partially offset the efficiency gains of electric cars). AVs may well emerge as part of an evolving mobility ecosystem as a variety of innovations, including connected cars, new mobility business models, and innovations in urban transit, converge to reshape how we move people and goods from place to place.

“The narrative on AVs suggests the replacement of human drivers by AI-based software systems, themselves created by a few PhD computer scientists in a lab. This is, however, a simplistic reading of the technological transition currently under way…

“Take, for instance, a current job description for ‘site supervisor’ at a major AV developer. The job responsibilities entail overseeing a team of safety drivers focused in particular on customer satisfaction and reporting feedback on mechanical and vehicle-related issues. The job offers a mid-range salary with benefits, does not require a two- or four-year degree, but does require at least one year of leadership experience and communication skills. Similarly, despite the highly sophisticated machine learning and computer vision algorithms, AV systems rely on technicians routinely calibrating and cleaning various sensors both on the vehicle and in the built environment. The job description for field autonomy technician to maintain AV systems provides a mid-range salary, does not require a four-year degree, and generally requires only background knowledge of vehicle repair and electronics. Some responsibilities are necessary for implementation—including inventorying and budgeting repair parts and hands-on physical work—but not engineering.

“The scaling up of AV systems, when it happens, will create many more such jobs, and others devoted to ensuring safety and reliability. Simultaneously, an AV future will require explicit strategies to enable workers displaced from traditional driving roles to transition to secure employment.”

Worth thinking about, isn’t it?

Collaborating with critics

In his recent lecture at Edge.org, Daniel Kahneman, a professor of psychology who won a Nobel prize for economics, and the author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, talks about what he calls adversarial collaboration, working with people with whom you disagree. His argument is not that our disagreements will disappear, but that our minds will become broader.

He says, “The feature that makes most critiques intellectually useless is a focus on the weakest argument of the adversary. It is common for critics to include a summary caricature of the target position, refute the weakest argument in that caricature, and declare the total destruction of the adversary’s position. It’s rare for anyone to concede anything in replies and rejoinders. Doing angry science is a demeaning experience. I’ve always felt diminished by the sense of losing my objectivity when I get into the mode of scoring points in a debate. I hated it so much that I adopted a policy that Amos Tverksy thought irresponsible: I do not respond to hostile papers. And if a submitted manuscript makes me angry, I do not review it.

“Because I did not like published critiques, it was natural for me to suggest a collaboration when I found myself disagreeing with a piece of research. All the more so because the adversaries were friends.”

He shares a number of stories from his experience with adversarial collaboration. One of them goes like this. “…two people I had considered friends, who wrote a very aggressive comment on a paper I had published about the evaluation of experiences. When I read their piece, I suggested an adversary collaboration as an experiment, but they turned me down. One of them said he thought a controversy would be more interesting. I wasted a lot of time doing something I had decided never to do—writing a snide reply to their critique. On the day before my reply was due, I decided to write to those people, those former friends, pointing out that our exchange of biting comments would hurt all our reputations. And I suggested a format for a joint piece to replace the reply-rejoinder.

“We started by stating what we agreed on, then we presented conflicting views on a series of topics. The outcome was vastly better for everybody than the alternative, and we ended up on civil terms. In general, a common feature of all my experiences has been that the adversaries ended up on friendlier terms than they started.”

He ends the lecture with a quote from Barb Mellers, that’s worth framing. “Do not change minds, just open a little wider.”

Dig deeper

A war foretold

Chris Hedges is an author and Pulitzer-prize winning journalist who has earned a reputation over the years for his reporting on wars from across the world including the former Yugoslavia and Iraq. While he has admirers, he has detractors as well. Having said that, it is difficult to ignore him either. That is why one of his most recent posts on how to look at events unfolding in Russia and Ukraine had our interest.

“I was in Eastern Europe in 1989, reporting on the revolutions that overthrew the ossified communist dictatorships that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was a time of hope. Nato, with the breakup of the Soviet empire, became obsolete. President Mikhail Gorbachev reached out to Washington and Europe to build a new security pact that would include Russia…

“The commitment not to expand Nato, also made by Great Britain and France, appeared to herald a new global order… There was a near universal understanding among diplomats and political leaders at the time that any attempt to expand Nato was foolish, an unwarranted provocation against Russia that would obliterate the ties and bonds that happily emerged at the end of the Cold War.

“How naive we were. The war industry did not intend to shrink its power or its profits. It set out almost immediately to recruit the former Communist Bloc countries into the European Union and Nato. Countries that joined Nato, which now include Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Albania, Croatia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia were forced to reconfigure their militaries, often through hefty loans, to become compatible with Nato military hardware.

“There would be no peace dividend. The expansion of Nato swiftly became a multi-billion-dollar bonanza for the corporations that had profited from the Cold War. (Poland, for example, just agreed to spend $6 billion on M1 Abrams tanks and other US military equipment.) If Russia would not acquiesce to again being the enemy, then Russia would be pressured into becoming the enemy. And here we are. On the brink of another Cold War, one from which only the war industry will profit while, as WH Auden wrote, the little children die in the streets.”

Dig deeper

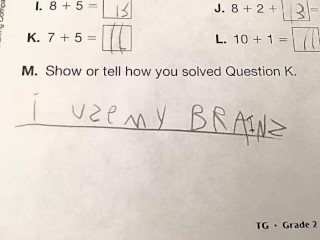

How kids solve problems

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel