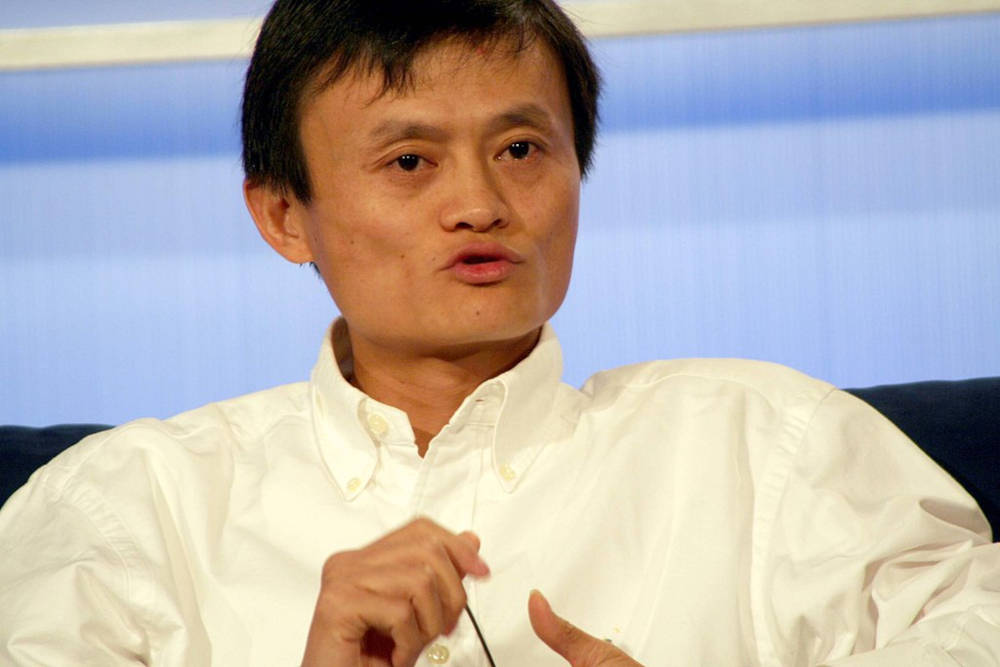

[Photo by JD Lasica from Pleasanton, CA, US, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Earlier this month, Jack Ma, co-founder of consumer retail giant Alibaba Group, failed to turn up for a television show on which he was to appear as a judge. In normal circumstances, it wouldn’t have been a big deal. But, these are extraordinary times. Ma, one of the most visible faces of China’s economic success, had literally disappeared after the suspension of Ant Group’s IPO. (Ant is an affiliate company of Alibaba.) There’s no word of him yet (even though a private equity investor in Alibaba has offered that Ma was safe and sound, but lying low). There is talk that the Chinese government might nationalise Ant Group. By many accounts, the story started towards the end of 2020.

In November last year, Chinese regulators suspended Ant Group’s Initial Public Offering, sending shock waves in the world of fintech. The $37 billion IPO, the world’s largest ever, was set to be listed on the Shanghai and Hong Kong stock exchanges. Following the suspension, the country’s four regulators, the Peoples’ Bank of China (PBOC), China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), and State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), said they would supervise and guide Ant Group’s functioning from now on.

Many believe the regulatory pushback is a punishment for Ma’s speech a few days earlier. In the speech, the billionaire criticized the Chinese financial system for its ‘pawnshop mentality’, (and the explanation goes) Chinese authorities wanted to stop his muscle-flexing right there.

However, the troubles for Ma started much earlier than his ‘pawnshop mentality’ speech. In fact, the uneasy relationship between China’s fintech sector and the regulators was brewing for some time. It’s just that they were waiting for an opportune time to deal a blow with the right ammunition. Puncturing the brand Alibaba just moments before its historic IPO was perhaps too alluring an option for the Chinese Communist party.

To understand why, we have to answer a few questions.

- Why Alibaba and why not any other fintech company, like Tencent?

- What were the factors that forced Beijing to clamp down on a behemoth like Alibaba now?

- What issues will continue to confound us regarding the future of innovation in fintech in a market like China?

Too big to trust?

Why Ant Group? It’s big. Alibaba, which owns a third of Ant Group, is a marketplace, a search engine and a bank. Its retail sales account for 20% of China's total retail sales. (To put this in perspective, Amazon's share of total retail sales in the US market is only 5%.) Out of these, three-fourths of its total retail sales are through ecommerce. A total of 750 million people, half of China's population, shopped online from September 2019 to September 2020, The New York Times reported. The Ant Group owes its origin to the e-payment facility, Alipay.

Chinese authorities have been increasingly wary of big businesses in recent years. In the last four to five years, the Xi Jinping regime has come down hard on the top bosses of some financial powerhouses. For example, the Anbang Insurance Group which acquired New York-based luxury hotel brand Waldorf Astoria in October 2014. It was taken over by Chinese regulators in February 2018. The regulators said they were doing this to protect consumer interests in some vital insurance products and there was imminent danger of insolvency. The group’s chairman was sentenced to 18 years in prison and was charged with embezzlement of funds and fraud.

Similarly, the HNA Group, a major conglomerate and hotel investor that emerged out of Hainan Airlines, ran into rough weather with the regulators. In September 2020, HNA group’s chairman was barred from buying tickets for high-speed trains and flights. He was even barred from vacations due to the Chinese conglomerate’s failure to pay a court-ordered $5,300 in a lawsuit.

The recent action against Ma is one episode in a series of crackdowns. Ma’s criticism of the Chinese financial system in the presence of senior party leaders was just a trigger, but a trigger from a business that has grown too big.

It should also be seen in the global context. In the US and the EU, governments have been wary of the frenetic pace at which tech companies like Google and Facebook are growing. They have also expressed concerns regarding the propensity to leverage their dominance.

In China, such concerns are even higher. No less than the Chinese President Xi himself stated that financial stability is part of national security. Further, the leadership made it explicit that finance is too critical to be left to the private sector. Underlying such concerns were Alipay’s revenues, which mostly came from its lending businesses.

It’s the finance, stupid

Ant’s fast-growing Credit Tech consumer business is based on its access to huge chunks of consumer data, which enables it to play the matchmaker’s role between borrowers and its partner banks. This arrangement made regulatory authorities very jittery. Ant was funding 2% of its total loans, with the majority coming from its partner banks. It was extracting an estimated fee of 2.5% for every loan, and it bore no risks. More importantly, this financial engineering led to 40% of its total sales.

Alibaba allegedly adopted questionable tactics (like forced exclusive arrangements with merchants, called ‘pick one of two’) to boost its revenues. For instance, microwave ovens maker Galanz accused Alibaba of diverting traffic from its online store, T-Mall, once it started selling on Alibaba’s rival website Pinduoduo. Merchants like Galanz observed that their page ranks started taking a heavy beating once they began selling on rival ecommerce platforms. Similarly, Alibaba has also been accused of forming captive ecosystems and preventing sharing of links by customers making purchases on its ecommerce platforms within WeChat.

Regulators have started taking these allegations seriously, and launched antitrust investigations, citing a) unsound corporate governance practices, b) indifference to law, c) turning a blind eye to compliance requirements, and d) engaging in ‘regulatory arbitrage’.

Alibaba had a brush with regulatory authorities even earlier. Regulators were wary about Alibaba venturing into wealth management and paying higher interest to those who were parking their money in Alipay’s wallet, which led to the de-crowding of deposits in state-owned banks. Alipay’s money market fund, called Yu’ e Bao (account-balance-transfer), was launched in 2013. It allowed anyone to deposit even meagre amounts to earn higher interest rates than deposits in state-owned banks, becoming the world’s largest money market fund. Regulators tried to deal with the situation by imposing limits on lower-quality assets and higher liquidity norms.

When the state is your competitor

One of the most critical factors compelling Chinese regulators to clip Alibaba's wings has been to reclaim the fintech space. Recently, the Chinese government announced its plans to establish a central bank digital currency (CBDC). The CBDC is projected as China’s big step to introduce a digital version of renminbi (RMB). The digital RMB is named Digital Currency/Electronic Payment (DCEP). It will primarily operate via smartphones.

This initiative serves various purposes. To begin with, this will help Chinese banks take back the digital payment domain from Alibaba and WeChat. According to a PricewaterhouseCoopers study, 86% of people in China used mobile payment platforms to make purchases in 2019. The party-state is more than keen to take back the space dominated by the private players. According to a study titled ‘China Power Project’ under the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies, in the fourth quarter of 2019, Alibaba controlled 55.1% of China’s mobile payments market. Tencent was not far behind, controlling 38.9% of the market—leading to a duopoly over trillions of dollars in mobile payments. China’s DCEP will be administered via a two-tiered system with the Peoples’ Bank of China issuing digital currency to commercial banks, which will then provide it to individuals. This system will lead to the transfusion of new life into the traditional banking system, which will have an adequate bite to compete with dominant players like Alibaba and Tencent.

Apart from the revival of the traditional banking system dominated by state-owned banks, DCEP will boost the RMB’s internationalization, one of the critical long-term goals of China’s leaders. DCEP will be functional even without a bank account or internet facility. As of 2017, 20% of Chinese adults (225 million people) didn't have a bank account, which is mandatory for accessing mobile payment platforms and other institutional services. Besides, DCEP can increase the number of consumers enjoying access to the ecommerce market. According to eMarketer, a market research company that provides insights and trends related to digital marketing, media, and commerce, the Chinese ecommerce market in 2020 was estimated to be the largest globally. At nearly $2.1 trillion, it is more than twice the size of North America's combined ecommerce market and more than three times Europe’s. Finally, DCEP will enhance the government’s capacity to keep a tab on economic activities conducted online. Real-time data on various online transactions could add more to the authorities’ e-governance capabilities by enabling them to check illicit and corrupt practices online.

Success begets scapegoating

This time around, Chinese regulators decided not to accommodate Alibaba. Analysts feel that this is symptomatic of a deeper malaise in Chinese society. This malaise has become more severe in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak. Growing inequalities in Chinese society accentuated by the coronavirus blues have suddenly made the Chinese very vocal about their dissatisfaction. On the one hand, China has more billionaires than the US and India combined, but more than 600 million earn less than $150 a month. In the first 11 months of 2020, average consumption decreased by 5%. Still, its luxury consumption was expected to grow by 50% in 2020 compared with 2019.

Further, the Chinese leadership is sensing the resentment that’s coming from various quarters—the youth are disgruntled about their employment prospects; and first-time home buyers are facing increasing prices in the real estate market and high interest rates on home loans. On top of this, the US and the international community have stepped up anti-China rhetoric. More than ever, President Xi was facing pressure to re-establish the party as the sole Leviathan. The result: Ant Group’s wings got clipped.

Outside-in Vs Inside-in: The two perceptions of Jack Ma

The Chinese Communist Party is adept in manipulating symbolic figures to mobilize domestic constituencies on nationalist lines. One of China’s role models is Zhang Jian, a 19th-century capitalist. This time the party leadership led by Xi invoked Zhang Jian's legacy by portraying Ma as too obsessed with building his brand and business fortunes and not appreciative of the state's efforts to control risks. According to a Chinese saying, ‘The modest receive benefit, while the conceited reap failure. Benefit goes to the humble, while failure awaits the arrogant.’ In Ma’s case, there was a growing feeling that with his expanding empire, he was getting too arrogant and intoxicated. A wealthy person with strong social and economic influence is reckoned politically dangerous in Chinese culture. The party wanted to encash on widespread discontent with the rich and the famous, like Mao who was portrayed in online chatrooms as an ‘evil capitalist’ and a ‘blood-sucking ghost’.

The big questions for the coming weeks

Chinese regulators’ recent antitrust investigations have cast a shadow on further innovation in the fintech domain. There are questions to which we are yet to find the right answers.

- Do the recent events bear evidence that Ma crossed the old line or do they reflect the overhauling of the fintech domain?

- Will entities like Alibaba and Tencent be asked to restrict themselves to ecommerce or will they be treated like banking units?

- Can the regulators avoid a last-minute showdown that could deal a body blow to a brand that could have been portrayed as a home-grown tech brand and a cause for celebration, especially when China is sparring with the US in the tech domain?

- What motivated the Chinese leadership to sacrifice this moment of national reckoning and achieve higher political goals?

- How will the new regulations impact not only the tech giants but other adjacent businesses built by them?

- Is the Ant Group’s IPO postponed or abandoned?

- Finally, do the recent developments mirror the growing influence of the ‘risk-averse’ conservative faction against the more market-friendly ‘pro-growth’ faction?

It’s a developing story. Watch this space.