Ground Realities is a blog, anchored by the team at Quipper Research, led by its co-founder and CEO, Piyul Mukherjee. It is an attempt to understand what’s happening inside people’s homes, in their lives. You can read the entire series here.

By Ishani Ray, Nishtha Jaiswal, Saawani Rajadhyaksha, Sharmistha Adyanthaya, Dali Agarwal, Aradhana Varma and Piyul Mukherjee

Schools have now remained shut for over 500 days—250 million children in India have remained home for this length of time. In a country with burgeoning inequality, the adverse effect on malnutrition and mental health, apart from the complete vacuum in learning, boggles the imagination.

We are informed that one in four children in India have access to digital devices. Within this world of the ‘haves’, a few parents had made evolved choices and sent their children to ‘alternative’ schools that emphasise experiential and tactile understanding, rather than rote learning.

These schools were supposed to nurture a love of life-long learning and better equip children as they inevitably get swept into the rigours of competitive scores in high school and college.

Post pandemic, what is happening in these homes where both parents hold down corporate careers?

We deep dive to discover the palpable angst of two nine-year-olds as the schools they looked forward to, got replaced with drab virtual one-way monologues by teachers they earlier loved. We speak to two working mothers who believe they are caught between the devil and the deep blue sea.

The ongoing upheaval is burdensome for moms as much as it is for young children who are at a critical age of cognitive development. Education is now channelled over to the mom, even as she juggles a new set of workplace pressures and additional household chores.

But the real victims are the kids. Bewildered and lost in a new normal where the joys of play, friendships, curiosity and learning have abruptly paused. Their laughter and silly banter that the schoolroom allowed, is muted.

“We pay the school to teach all this, why should I do it anyway?”

Sharonne*, works as an HR manager in a global FMCG company

A Kerala native who grew up in Mumbai.

Resides in an owned 2 BHK in suburban Mumbai, where she lives with her husband, a wealth manager, and two daughters aged eight and four, who are in Grade IV and Junior KG, respectively. Her in-laws often visit them from Kerala.

She chose a school following the Montessori method of schooling for her daughters.

Aditi*, senior journalist with a reputed publication

Grew up in a small town in Assam.

Resides in an owned 3 BHK in suburban Mumbai, where she lives with her husband, a freelance journalist, their nine-year-old daughter and live-in helper.

She chose a school following the Waldorf method for her daughter who is now in Grade IV.

*names changed

A sandpaper pit of shapeless cutouts lies discarded in a corner of the children’s room—a remnant from Sharonne’s early attempt to replicate the creative learning method her daughters were used to at their Montessori school. “I have no experience in teaching kids with these methods. I myself never even learnt alphabets through phonics. We pay the school to teach all this, why should I do this anyway?” she asks.

In another part of suburban Mumbai, Aditi feels equally overwhelmed at being pushed into the role of a teaching facilitator for her nine-year-old—a role she never signed up for.

She feels let down on many fronts.

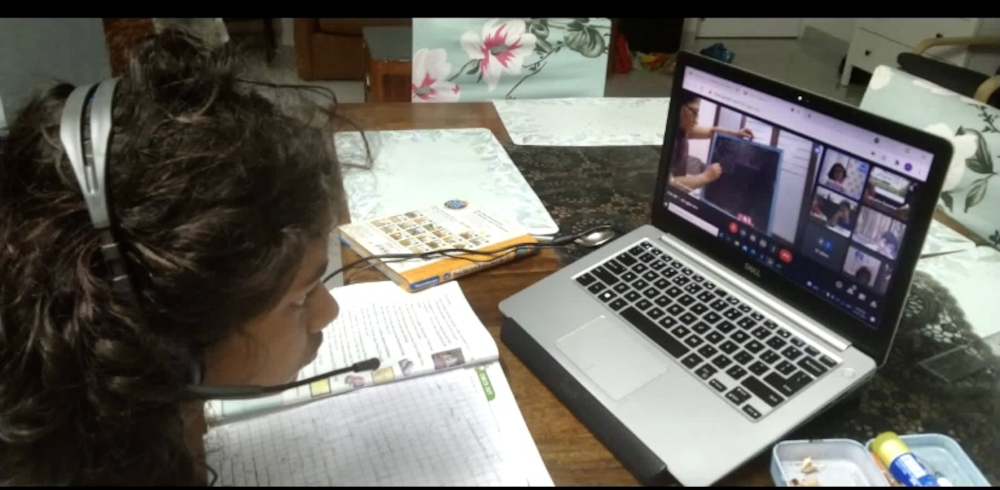

Multitasking has taken a whole new meaning. There’s housework in the absence of domestic help, office Zoom meetings, and the responsibility of policing the children during online school. “My husband usually is in the other room to focus on his work during office hours, so I had to make adjustments to be around, during online classes,” says Aditi.

Sharonne and Aditi have learnt to share the dining table with their kids, while being on a Zoom call themselves. Leading to a clash of sounds, activities and inevitably, moods.

Teachers expect one of the parents to be around, as students struggle with the new online format. They expect parents to engage and participate in their child’s learning process. Because in reality, all “digital learning” has meant is old systems transplanted to an online platform. This is as true for alternative education models. The institutions that had earlier promised a complete hands-off experience to parents, are struggling to adapt and now insist on parental monitoring and hand-holding during classes.

These harried mothers appreciate the need, but feel it is impossible for them to step in and fill in the void. They rebel at needing to take on a responsibility that had hitherto been placed on the shoulders of the new-age schools.

Aditi is even more angry at the decidedly sub-optimal learning experience, given that private schools continue to charge the same fees as earlier.

Sharonne believes the school has only made it tougher with their expectation that she must hang around during classes to ensure the children are not distracted. “It is embarrassing when I have to postpone office meetings, expecting others to adjust because I have to be with my daughter.”

Aditi’s attempts are limited to trying to get her daughter to understand some of the subjects she is struggling with. Her husband, who was always actively engaged in their daughter’s sporting pursuits, makes sure they go for regular walks and outdoor explorations, but that is the limit of his engagement with the child’s education.

“The principal told parents to consider involving them in household work to teach them the importance of camaraderie in crisis,” adds Sharonne. But these concepts were “easier said than done”. Folding clothes—probably a fun team activity at school—did not quite work out in the home. The child refused to cooperate.

All this has left both Sharonne and Aditi frustrated and without the energy to even strive to replicate activities or the tactile teaching environment their children enjoyed in school, and that the teachers are now asking of them. “I do not have the expertise or patience, not to mention the time,” says Sharonne. “This is not what we envisaged at all.”

With no end in sight, parents are flailing between a face-off with schools on providing creative solutions and their own time crunch.

Sharonne and Aditi had made a conscious decision to send their kids to a Montessori or a Waldorf school. Having themselves suffered through rote learning, they had wanted to ensure that their daughters got a chance to develop a love of learning. “My husband and I wanted holistic development for our child,” recalls Aditi. “Many parents wondered at our choosing an alternative education school; some even asked whether our kid has some development issues. But my daughter loved every day at school and that is all that mattered.”

With their busy careers they recall being relieved that the school expected very little engagement from the parents and in fact encouraged independent learning.

Sharonne has fond memories of the pre-pandemic days: “In school, they had fun conversations and learnt through songs, music, beats, poetry and structured play. Earlier in a physical lesson, they would often give kids a set of wooden tools. The teacher would then take one such tool-kit and explain mathematical division using them. Now, it’s completely unidimensional with blackboards, chalk, and diktats. My daughter just cannot grasp the concepts.”

Most parents thought the abrupt pause in learning and the half-baked online school solution was a phase that would pass without any long-term damage.

“My biggest concern as a parent has always been that you have to validate the child’s feelings, even the negative ones, rather than worrying so much about what they’re learning or eating or doing,” says Aditi.

Her daughter now struggles with the traditional format of being taught on a board that is visible through the laptop screen. There is a complete loss of focus on sensory development, a key tenet of this learning experience.

“Now in the Hindi and Marathi class, I often find my daughter staring blankly at the screen, sometimes yawning, as the teacher continues with the lesson. Syllabus-completion has suddenly become more critical than the learning experience,” says Aditi. She concedes that teachers do try to make teaching fun but there is no consistency.

Teachers expect children to remain quiet and not disturb the class. They insist that children keep their audio on mute during lesson time, and ask questions at the end. Quite the damper for nurturing spontaneous creativity and interactive learning for primary school kids. Her inherently curious daughter, Aditi says, is fast losing her voice.

Aditi’s grouse is accentuated by the fact that a school that earlier discouraged the use of devices has now actively played a role in hooking her previously outdoors-loving daughter to the glitz of the virtual world. Perforce, these parents had to buy laptops and phones for their children. Most working parents grudgingly accepted this as a collateral of the pandemic.

Stuck in her Mumbai high-rise, and loss of the routine she thrived off, has led to behavioural issues. “She was an energetic kid who loved the outdoors and played various sports. Now she is mostly lethargic and would rather remain glued to the screen.”

Sharonne too feels the pinch of this early entry of her four-year-old into the virtual world. “Earlier, my younger one would ask a lot of questions to understand why things are a certain way. But now, she Googles it or watches a video. And even with that she uses the text-to-speech function, so her writing and spelling aren’t getting developed,” laments Sharonne. “My younger one was a happy and observant child. Now she has become easily irritable.”

“I just cannot understand my child’s silence nor her anger,” say the parents who have become helpless spectators to the changes in their once energetic daughters.

“Teachers shout and parents do not have time for me”

Anushka*, nine years old

A fourth-grade student at a well-known Waldorf school in Mumbai.

Lives in a 3 BHK apartment in an upscale Mumbai suburb. Her mom, who is a cancer survivor, and her dad are journalists.

Nidhi*, eight-and-a-half years old

A third-grade student at a reputed Montessori school in Mumbai.

Lives in a 2 BHK apartment in suburban Mumbai. Both parents are working professionals. Her grandparents live in the same apartment.

*names changed

Nidhi recalls a recent memorable day at school. The history teacher was unexpectedly absent from online school. “The teacher did not show up. We filled the chat box with emojis, and watched each other doing whatever they do at home. We talked and talked and talked, and my friend’s bird escaped from the cage.”

Imprisoned every single day in front of their laptops, Nidhi and Anushka wistfully recall the smallest detail of life at school. “Real school”, as they call it.

“During recess, we played lock and key.”

“When the teacher was not there, we threw pencils at each other and banged the desks together.”

“I miss my friends tickling me in class and us doing funny tricks together.”

Not one memory is related to getting ‘educated’. All memories are to do with interacting with friends.

They miss the small, routine activities of the day. Being yanked out of bed, rushing to get ready, eating a quick breakfast, and brushing hair while running out the door, packing a snack for the school bus.

Now, during classes, they are expected to maintain decorum, remain silent and not interrupt the teacher. “Teachers have become more shouty,” say both the girls. This is not how they remember the same teachers, which further heightens their confusion. “My Shilpa ma’am was really, really nice. She would teach us mental math while doing gardening at school.”

Now, in online classes, it seems the teachers don’t need a reason to yell at the students.

“For coming into class five minutes late, for asking questions in the middle, for not knowing the answer if the teacher asks, for looking up at the ceiling,” shrugs Anushka.

Children are more tech savvy, so sometimes they know how to resolve issues the teachers are facing online. But they keep quiet as they’ve realised most teachers are unwilling to be shown what needs to be done by the students.

Now Nidhi sits down at her work-table for school by 9 am and listlessly stares at the screen, where the teacher is using a blackboard. Something that was rarely used in her “real” classes, where teachers used all sorts of aids to teach concepts. She shares her class with twenty students, and that in itself is a sign it’s one of the better schools in the city.

Nidhi’s attention wanders but she has learnt to keep staring at the screen even though she’s not paying attention.

“If we unmute ourselves to ask questions, the teachers shout. They spend half the class shouting. We don’t really learn much. I hate everything,” says Nidhi indifferently.

Anushka too finds it hard to pay attention as she sits through eight classes a day—all sitting in front of a laptop screen. She’s slightly older and in an older class, and has figured out that with the camera on, she can open a parallel window and watch something else. Watching Netflix on mute, she says, is better than dozing off and being taken to task by the teacher.

“In any case, the teacher is going to send an assignment, and she does not allow me to ask questions,” says Anushka.

All education-related doubts are to be taken to the mom.

Since they’ve grown up with both of their parents working, Anushka and Nidhi were accustomed to not having grown-ups around all the time. At first, both girls recall being delighted that their parents were home all the time. But cynicism has set in. “My dad likes to accompany me on walks and we try to play some sports together,” says one. “My dad actually is mostly free, but he does not understand my studies,” says the other.

Moms, now the de facto teachers, are mostly seen to be harried with less time for their children. “My mom scream-talks every day during her meetings. I can hear her from the hall with the TV on!” says Nidhi. There is nobody, both the girls feel, who is actually teaching them anything by actual demonstration.

The girls live in fear of the unknown. They’ve seen family members suffer serious illness—Covid in one family and cancer in the other.

Mental health experts are now worried about the high levels of stress that children may be experiencing. For millions of children across the world, everything they knew about the world changed overnight. They no longer go to the playground, or meet their friends or go to school. They are suddenly confined to the four walls of their home and in Nidhi and Anushka’s case, their tiny Mumbai apartments.

The last 18 months have been a very lonely experience for the children. There’s a feeling of suffocation.

“I am really, really, r-e-a-l-l-y bored,” says Nidhi, “I was never ever bored in my life in real school.”

Anushka has spent the last year hearing words like ‘chemotherapy’, ‘co-morbidities’, ‘ventilators’ and ‘oxygen shortage’. “I thought mom would get corona as she has a weak immune system and she has undergone two surgeries. I felt sad and alone and scared.”

“I shout into my pillow,” she says. “My pillow is my best friend. I scream into it every night.”