[Clockwise from top: Xi Jinping arrives for the opening meeting of the fifth session of the 13th National People's Congress at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, on March 5, 2022; Xi learns about the local efforts to promote scientific and technological innovation in enterprises while visiting the exhibition hall of the Siasun Robot and Automation Co Ltd in Shenyang, China's Liaoning province on Aug 17, 2022; Xi meeting the press at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China, Oct 25, 2017. Photos/Xinhua]

The Communist Party of China (CCP) will hold its 20th party congress in Beijing, starting October 16. The highly secretive week-long meeting takes place every five years, at the Great Hall of the People on the western side of Tiananmen Square in central Beijing.

This meeting will be one of the most momentous events for China watchers, for it is likely to ring in new directions in Chinese domestic politics and foreign policy—and India is watching too, as it has geopolitical and foreign policy implications for the country. Already highly secretive deliberations have been taking place in the various high-level meetings ahead of the congress.

The questions on the minds of China watchers: will the party congress herald a new era of factional ‘politics with Xi Jinping characteristics’? Or will Xi exercise his authority but also be conscious of respecting some of the traditions of the party in the name of ‘collective leadership’? And what clues can one get from the ‘new leadership’ team—a fresh crop of leaders likely to come into the top decision-making bodies—regarding China’s priorities in its domestic and foreign policy-making?

In other words, will the new leadership connote something more than merely an exercise in settling political rivalries? And how does one make sense of any connection between the new administration and China's geopolitical ambitions in this decade?

A power shift—and a new world view

From the perspective of China’s domestic politics and governance, Xi Jinping, the current President of the People's Republic of China and the general secretary of the CCP, will assume office for a third term. The established practice was to choose a successor before the end of the second term, but Xi engineered a constitutional amendment during the 19th Party Congress in 2017, ensuring that he stays at the top for a third term. In the post-Mao era, this is unprecedented.

According to many analysts, this will be a formal declaration of Xi’s complete control over the party. According to some informed sources, Xi is likely to be designated the Chairman of the CCP—a title so far held only by China's paramount leader Mao Zedong.

While Xi’s ascendance seems to be a given, who will form the ‘new leadership’ of China’s top decision-making bodies is a matter of immense speculation. These newly appointed leaders are expected to be from the sixth and seventh generation (born between late 1950s-1960s, and in the 1970s, respectively) of the party leadership.

This power shift to a new generation is significant for several reasons. First, most sixth-generation leaders have benefited from China’s economic modernisation drive. They have studied in prestigious universities abroad, many have doctoral degrees in niche areas like aerospace, AI, and environmental sciences, and some have headed China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs). (Their experience is unlike the previous generations of leaders who had to display the highest degree of loyalty to the party under trying circumstances. They participated in political purges; during the Cultural Revolution, launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, many were sent to harsh rural conditions. Fifth generation leaders like Xi were in their teens and were part of this group termed ‘sent-down youth’.)

The new leaders’ have had exposure to a wider world, which might have a different impact on China’s policy making when they occupy seats in the topmost decision-making bodies of the party:

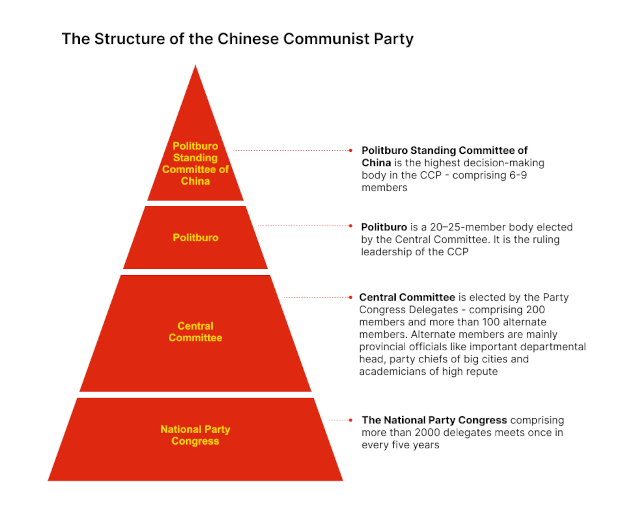

- The Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC, there could be more than 2-3 new leaders in the typically 7-11 strong committee). The most powerful party leaders make up the PBSC. They deliberate on policies of domestic and international importance when the Politburo is not in session.

- The Politburo (PB, possibly more than 7-11 new leaders in the 25-member entity). Its members occupy crucial positions in the central government or have powerful regional roles like party secretaries and mayors of important provinces and cities (called state council, led by the premier). The PB’s decisions are made on the basis of consensus rather than majority votes.

- The Central Committee (CC, with more than 200 full members, and more than 150 designated as alternate members). Full members have voting rights; alternate members’ role is limited to participation in deliberations and voicing their opinions. The CC is the formal body that elects the PBSC and the PB and formally appoints the general secretary of the party. The CC also oversees the work of various national bodies of the CCP. Its members comprise party chiefs, governors of provinces, mayors of cities, central ministers, regional heads of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and heads of various institutions.

Second, the composition of these three top bodies will convey an updated understanding of the intra-factional power equations within the party congress. (See graphic on factional politics through different eras in China’s politics.)

In the CCP, every era has been characterised as an era of one major leader. However, except for the Mao era, the party has largely functioned on the basis of collective leadership. During the Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao eras, the party’s highest bodies had members from the various factions. In other words, irrespective of the topmost leader’s authority, till now the topmost bodies always comprise members from different factions. However, the composition of these bodies convey the powerful influence of the numero uno.

Xi’s ten years of rule have been no different. He has very shrewdly nurtured a set of supporters by outmanoeuvring the leaders of the other factions. According to informed sources, Xi’s foreign travels a few weeks before the party congress conveys that he is in complete command of the situation with no significant threat to his position. The constitution of the three topmost bodies in every party congress provides clues to what lies in store for the next five years.

Third, bringing in new leaders perhaps signals shifts in China’s domestic and foreign policy. Admittedly, there are mixed signals emanating from China. For instance, the demotion of the first vice foreign minister Le Yucheng, a pro-Russian diplomat and earlier tipped to be the new foreign minister, is being interpreted as a scaling down of Xi’s support for Russia’s war with Ukraine. According to some analysts, this move was to kick-start talks with the US and also accommodate voices from within the party’s top brass who are not happy with China’s support for Russia in its prolonged war.

On the domestic front, the shift in direction is imperative in the wake of recent crises—realty giant Evergrande missing debt repayment deadlines in 2021 and the troubles in the real estate sector; the suspension of the Ant Financial IPO in 2020, the world’s largest at that time, and a dampening of spirits among private corporates because of Chinese authorities’ regulatory pushback (there were a series of crackdowns, including on some financial powerhouses like the Anbang Insurance Group, and on HNA Group, a major conglomerate and hotel investor); and open dissatisfaction, especially among the youth due to growing inequality and poor employment prospects, and home buyers who are stuck with home loan payments even as constructions have halted. The zero-Covid policy and recent lockdowns have not helped matters and are causing rumblings in the party at the topmost level.

Growing unemployment prompted Xi to call upon private capitalists to play an active role to fuel investment and growth. That meant that the banking sector was under pressure to extend more credit to SMEs, increasing the risks of an already worrisome non-performing loan crisis.

There have been reports of inter-agency battles with policy makers and central bank officials pitching for boosting growth whereas security regulators and planning ministry officials have preferred to be conservative.

China’s domestic situation in the last decade

How did China come to this point and why is a shift in direction critical? Here’s some context:

Xi’s various initiatives in the initial years can be traced to the global financial crisis in 2008.

A deliberate step-back: China’s development strategy based on export promotion and on attracting FDI, gave way to one based on boosting domestic consumption. The fiscal stimulus led to a tremendous spurt in economic activities in China—and in just about three years the economy overheated. Which prompted Xi to start new measures. To begin with, he called for a ‘new normal’ growth rate—China should not record an annual GDP growth rate beyond 6.5%. He also launched an anti-corruption campaign to target irresponsible spending by leaders at various levels which was adding to the woes stemming from non-performing loans.

Steering social attention: More than three decades of reforms had not helped the poor, especially in the interior and northeast and northwest provinces. The party needed to address any possibilities of a trust deficit from Chinese society. The calls for a ‘harmonious society’ under the previous regime of Hu Jintao had failed to address interpersonal and regional inequalities. Growing complaints and protests, especially at grassroots level regarding social inequality, emerged as major causes of worry for the party leadership.

Xi took on the task of steering China to a new course—based on his own adept concoction of a political and economic strategy.

Xi urged the Chinese to work to realise the ‘China Dream’ and not to forget the ‘century of humiliation’ (subjugation by Western powers and Japan from 1839-1949). He also announced that the time has come for China to claim its rightful place under the sun and decided to chuck the earlier strategy of ‘lying low’ for a more active policy based on what he calls ‘striving forward for achievement’.

BRI and political jugglery: Xi started the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 to overcome the ill effects of the post-2008 new normal. Some experts argue that the Chinese leadership came up with a masterclass in political jugglery with words. For the domestic audience BRI was presented as a ‘strategy’ to overcome the woes stemming from an overheated economy. For the external world it was an ‘initiative’ signalling China’s arrival in the big league and its readiness to assume greater responsibilities. Many have likened the BRI to the US Marshall plan during the earlier years of the Cold War.

Further, Xi sought to add a touch of benevolence to BRI by claiming that this initiative seeks to achieve a ‘community of shared values’ at a global level.

Tech competition with the West: To take China to the next level of development, Xi also decided to compete with the West in high-end technology.

He started the ‘made in China 2025’ policy and promoted a group of private players in the tech domain by crowning them as ‘national champions’, and investing heavily in robotics, AI, and Big Data.

Since 2017, Xi’s ‘grand steerage’—to use a term coined by noted China specialist Barry Naughton—involved enormous government-backed resources to drive a market-based economy. This ‘grand steerage’ aims to motivate policymakers to realise China's ambitious goals.

At the same time, the end purpose of this steering is to propel China to a trajectory of hi-tech manufacturing and ensure that technology permeates all aspects of Chinese society. The means to achieve these goals is by providing the optimal usage of instruments like investment funds, subsidies, and tax breaks.

These plans have been further refined. The 14th five-year plan (2021-25) laid down the new target of Vision 2035—an ambitious plan to achieve ‘socialist modernisation’ by 2035, as a mid-point objective on the way to building “a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious” by 2049, the centennial year of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. And the dual circulation strategy, articulated in 2020, where the Chinese economy will focus on domestic consumption while it remains open to foreign trade.

China seeks to acquire cutting-edge technology by promoting innovation in key and core technologies. Xi focused his economic development strategy on rapid industrialisation, building a stronger information society, driving urbanisation and modernising agriculture. The strategy also covers environmental sustainability, culture and education, and military modernisation. The Sino-US trade war, growing economic nationalism in many parts of the world, disruptions in tech value chains, and the Covid pandemic have added new urgency to these ambitious plans.

Tech-driven economic modernisation & rise of generalist vs. specialist factions

The likely new leaders post the 20th party congress have been carefully groomed to facilitate China’s tech-driven economic modernisation.

In a way this is not new.

Given the imperatives of economic modernisation during the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping recruited engineers into the party's leadership, resulting in the emergence of engineers-turned-leaders. The PBSC was dominated by such leaders after the 15th and 16th party congress.

From the time Hu Jintao assumed office till now, the party has witnessed a decline in the number of engineers-turned-officials. Hu’s emphasis on a harmonious society and balancing the goals of social and economic governance contributed to this decline in their numbers and the increase in the number of leaders from varied backgrounds.

As mentioned before, ‘Technocrats 2.0’—the new sixth and seventh generation leaders—have expertise in nuclear technology, aerospace technology, 5G, shipbuilding, robotics, AI, environmental sciences, and fintech. It is speculated that two-three of them will be in the PBSC and at least seven-eight in the PB.

Close scrutiny of their profiles reveals that these appointments align with China’s domestic and foreign policy objectives.

For instance, the ‘cosmos club’ (hangtian xi, also called yuzhou bang) refers to a set of technocrats who have made rapid strides through the party ranks owing to their expertise in the space and aviation industries. Experts keeping a close watch on the upcoming party congress believe that the cosmos club is most likely to occupy a new ‘political highland’ (zhengtan gaodi) on the eve of the congress. Some members of this club already occupy prestigious assignments like party secretaries in provinces like Xinjiang and Zhejiang and chair essential bodies like the State Assets and Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC).

The promotion of this group indicates the party’s intent to accelerate space industry development.

According to Cheng Li, an eminent expert on China's elite politics, a close look at the seventh-generation leaders shows that they have served considerable time heading financial institutions and industrial enterprises, rather than provincial administration. The promotion of experts in fintech and from SOEs is to ensure that the next group of leaders in the apex decision-making bodies can make China’s SOEs global players and, in the process, enhance China's economic presence.

It is worth mentioning here the Fortune Global 500 list for the year 2022 showed 145 Chinese companies contributing 31% of the total revenue of the world’s 500 largest companies. In 1995 China had only three entries in this list.

Financial technocrats make up another group of experts from the sixth and seventh generations. Many are already serving as the topmost officials in charge of economic affairs at the provincial level.

As China strives for achievement at a global level, maintaining financial security is intimately connected with national security concerns. A rising China—the world’s second largest economy—knows it now needs to be closely integrated with the international financial markets. Any faux paus on this front can undermine China’s interests.

Further, in the last decade, the Chinese leadership has asserted that political security comes first. China's growing footprint in international financial governance has fuelled an ambition to become a global financial powerhouse. But to deal with the challenges of staying the course, the party leadership will need the skills of financial technocrats with a global exposure. These experts-turned-officials are expected to have what it takes to shape and lead China's aspirations in the global financial world.

Apart from the geopolitical objectives, Xi’s political genius also motivates the formation of the new leadership team. This issue brings us back to factional politics in the party. Many of these sixth and seventh generation leaders have not spent too much time heading the provincial and local administration. Their fast-track promotion has ensured they do not develop networks and dig their heels into the world of factional politics. Less time in provincial politics also means they will be more amenable to national rather than local concerns, which has led to localism on earlier occasions. In addition, their recruitment will diversify the composition of the top leaders’ power base, making it harder for other factions to mobilise support for their cause. At the same time, fast-track promotions for these officials by Xi will ensure they exhibit loyalty to him.

So, what India must keep an eye on

In the last five years, the Sino-US trade wars, disruption of the tech value chains, the Covid pandemic, and more recently the Russia-Ukraine war, have not only made the world riskier for businesses, but have also impacted the common man with inflation in oil prices and longer waits for electronic gadgets in an online world.

In other words, in a highly interdependent world, an informed understanding of geopolitics and foreign policy-making is indispensable.

Foreign policy analysis calls for going beyond an understanding of the implications of what China does in our immediate neighbourhood in Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Nepal. It also extends to developing awareness about the political institutions, elite party politics and dominant interest groups in China. The upcoming party congress is perhaps the right time for us to unpack what has been largely treated as a ‘black box’ by the majority of Indians.

Join us on October 1

This essay is part of the run-up to a specially curated Masterclass on Making Sense of Xi-Jinping’s China on Saturday, October 1. We have a high-powered panel of China experts from India and abroad who will analyse Xi’s leadership journey—and where China is headed.

Don’t miss this Masterclass. To join, register by clicking on the button below.