Sometime back a tweet by a foreign tech correspondent in Beijing made me smile: "Illustrative of China's love for e-commerce: a coworker who will remain unnamed bought a toothbrush from JD.com yesterday."

I’ve been in China for three years now, and these things no longer shock me. I am used to seeing people buy everything from lipsticks and makeup to vegetables and fresh crabs online. The other day, as I stood in the office elevator, I saw a delivery boy from an e-commerce company that specializes in selling chopped fresh fruit to busy office goers. That, I feel, is a bit of a stretch and may be set for failure. But the fact remains that China’s bustling e-commerce market has created ample opportunities and for would-be entrepreneurs, the sky is the limit.

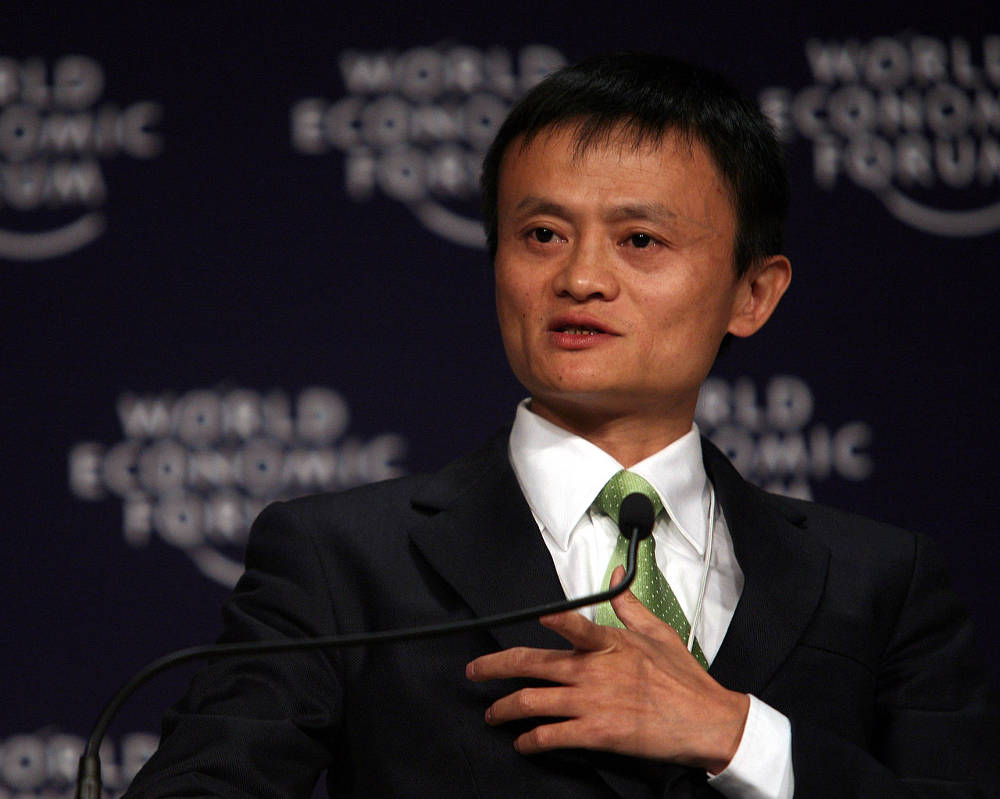

They all have just one man to thank - the first guy to dip his toes in untested waters - Jack Ma, founder and Chairman of China's largest e-commerce company Alibaba.

Before coming to China, I didn’t care much about Alibaba or Jack Ma’s story. I cared about eBay and Amazon. But after coming here, my worldview on e-commerce changed. Despite its massive success in the US market, eBay failed miserably in China. Alibaba's consumer-to-consumer (C2C) platform Taobao drove the final nail in eBay China’s coffin. Amazon, on the other hand, continues to languish in China with a miniscule market share. Alibaba's success has spurred other Chinese entrepreneurs to follow suit. Other Chinese e-commerce companies flourishing in this vibrant market include Jingdong (JD.com, previously known as 360buy.com), Yihaodian, Dangdang and Vancl.

Alibaba has revolutionized how Chinese shop - even seemingly mundane things like a toothbrush can be procured easily (and more cost effectively) online than by making a trip to the neighborhood 7/11 store.

So how did Jack Ma do it?

Solve a Big Hairy Problem

Before Alibaba came along, small Chinese manufacturers had execution capabilities and ambitions. But they had no means to connect with potential buyers. It was a fragmented landscape: a nation full of small, inefficient businesses that had no means to connect to the world outside and to each other either. Add to that the big language barrier that separates the Middle Kingdom from the rest of the world. Alibaba stepped in to fix that gap by setting up a Business-to-Business (B2B) platform that effectively acted as a bridge between importers across the world and small Chinese exporters. It literally opened the global market for small Chinese entrepreneurs.

Understanding the Market

Here’s something that eBay and Amazon had a hard time understanding: the Chinese are different. Ma set up Taobao, a C2C site, to fend off eBay. While sellers had to pay a fee for listing on eBay, Taobao was deliberately free. This appealed to small businesses.

eBay, with its deep pockets, splurged on ads on buses and subways, and signed exclusive advertising deals with internet portals, effectively cutting Alibaba out. Ma, who knew small business owners were less likely to surf the internet, blasted out ads on TV. That helped Taobao gain traction. To add to that, Taobao was more customer friendly than eBay. To a large extent, eBay was trying to transplant the model that it had in the West for the Chinese market and their senior executives had no prior China experience.

The other global e-commerce giant, Amazon, which has managed to survive in China albeit with a negligible market share of 2 percent or thereabouts, also operates with its big Western hat on. As a former Amazon China VP told me, "At Amazon, everything in the decision making process has to go through the system. You can't make your decision locally. You have to report to Seattle to get the decision made." It’s not hard to see why Alibaba, with its local expertise and nimble moves, beat these companies hands down.

Playing on the Chinese Psyche

This is Chinese e-commerce's best-kept secret: If you want to whip up customer frenzy, announce a flash sale. In 2009, Alibaba started leveraging what is called Singles' Day, or November 11, to do a 24-hour sale. Ever since, Singles' Day has lost much of its original meaning (a day to celebrate one’s single status) and has become a shopping extravaganza. In 2013, Alibaba's Tmall and Taobao ratcheted up sales of $5.75 billion in just 24 hours, higher than the GDP of some countries. In 2014, the figure stood at a whopping $9.3 billion. Alibaba has made online shopping an act to be savored and celebrated, and Chinese consumers are happy to play along.

Build a Supportive Ecosystem of Services

If you don’t have it, build it. That’s Alibaba's dictum. Today Alibaba owns, among many other things, a Paypal-like payment service called Alipay, a shopping search engine called eTao.com, cloud computing services under Aliyun, a lending platform for small businesses and individuals called Zhao Cai Bao and an internet finance arm called Yu’e Bao. It also has interests in a logistics network, a group buying business, a supermarket chain, a crowdfunding service for movie production and a taxi hailing app. Ma will dip his fingers in anything that will help grow the ecosystem - he won’t wait for others to do it. When Alibaba first got into e-commerce, there was nothing to enable secure online payments and thus Alipay was born. Alipay, with its in-built secure processes and escrow system, gave Chinese sellers and buyers peace of mind while transacting online. Today Alipay has grown beyond its original brief and has become a force in itself. Payments for Alibaba’s own sites account for a little over 37 percent of the total transaction volumes on Alipay.

Help Others Succeed, Because Scale Builds Scale

With its unique model, Alibaba has spawned a whole ecosystem of entrepreneurs and transformed the lives of millions of people across China. Before Alibaba came along, opportunities in China’s rural countryside were limited. Villagers did what they had always done - farm, raise livestock, sell petty products in the local economy. In one single sweep, Alibaba transformed villagers across the length and breadth of China into micro-entrepreneurs. It is estimated that there are 1.05 million active online retailers in rural China. As per a Taobao and AliResearch report, more than one-sixth of the six million-odd online stores on Taobao and Tmall are located in small counties and villages. Unlike other businesses, there are little or no barriers to entry when it comes to selling on the Internet and it is something that’s easy to do as well. Inspired by the one-off neighbor who made a fortune by producing something and selling it on Taobao, entire villages in China have taken to e-commerce.

Very often an entire village starts specializing in just one category, and ends up creating a mini industrial cluster. It is very common to see villages specializing in just furniture. Or just clothes for that matter. One little village in Guangdong is going one step further - working with the local government to set up a Taobao University that trains people on how to transact online. Some villagers are starting to take branding seriously.

Some of these villages have reached a critical inflection point and are now officially called 'Taobao villages'. As per the AliResearch and Taobao report, a Taobao village is one that has online stores for more than 10 percent of the local families and online transactions surpassed RMB 10 million. Going by this strict definition, there are 20 Taobao villages (the figure is up by 50 percent since 2012) across China in provinces like Guangdong, Jiangsu, Hebei, Zhejiang, Shandong, Jiangxi and Fujian. Former farmers and livestock breeders now own multi-million dollar businesses, drive fancy cars and vacation abroad.

These entrepreneurs have created a ripple effect on the local economies, employing people in manufacturing, packaging, logistics and other affiliated services. As per the Aliresearch report, the new Taobao villages (those added since 2012) created 60,000 jobs directly and several others indirectly, raising rural incomes in the process.

It is for this reason that Jack Ma - in the eyes of many across China and me - is a hero.

A condensed version of this article was originally published in Mint on March 24, 2015