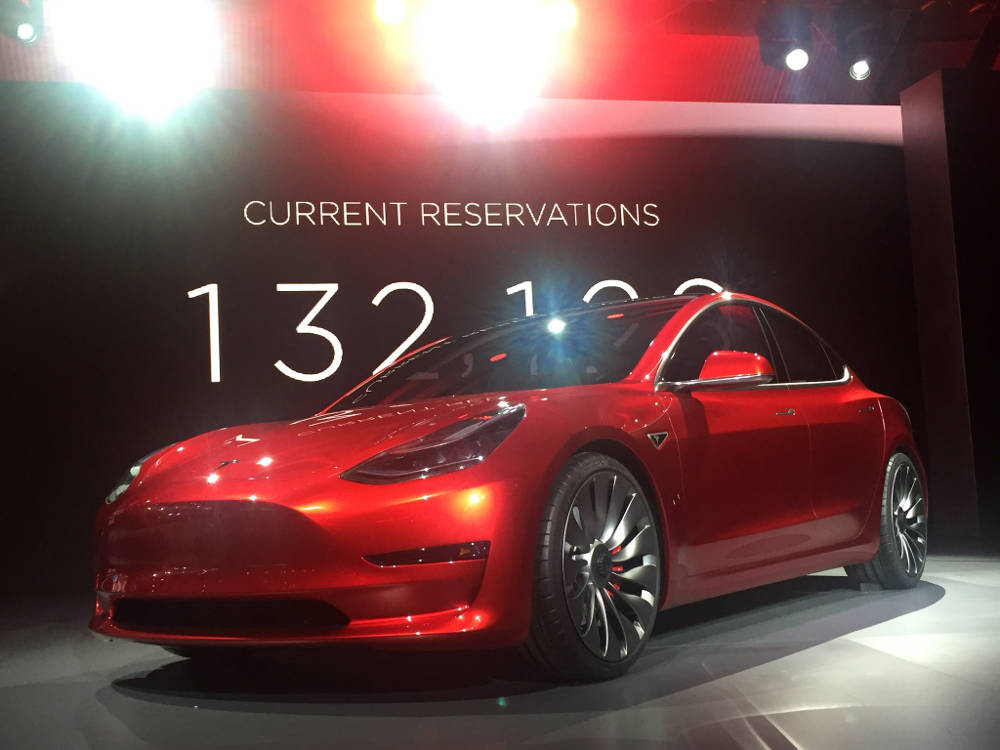

[Photograph: Tesla Candy Red Model 3 by Steve Jurvetson under Creative Commons]

Why Tesla has captured the world’s imagination and is it really clean and green

Tesla Motors captured the world’s imagination when it announced the launch of its “affordable” electric car Model 3, due in 2017. It will also be available in India. Even though a full prototype isn’t ready yet, it has managed to garner 400,000 bookings and collected an advance of $400 million, which translates into potential revenue of $14 billion, provided no order gets cancelled before the Tesla Gigafactory can start delivering it towards the end of 2017.

How did it achieve this feat? An obvious answer would be that Tesla cars are perceived as clean and green cars, even though Tesla’s (and other electric car makers’) environment-friendly credentials may lie in the grey zone—more on that later.

The triggers for customer preference

- Sustainability

The new generation of customers strongly believe in and support sustainability, but are often at a loss on how to engage in activities through which they can support this cause. So when they come across a brand which is sincerely supporting this cause, they vote for it with their wallets.

These customers care about the carbon footprint of their chosen means of transport. This means that value has migrated from mere transportation towards clean transportation.

Traditional car companies, led by General Motors, Ford, Toyota and others, still operate predominantly in the earlier value zone of merely providing a means of transportation, though many of them offer electric vehicles (EVs). Whereas Tesla is operating in the new value zone (clean transportation) as it makes only EVs. Hence the eye-popping booking figures for Model 3 even before the full prototype is ready.

Tesla does not depend on this perception alone to clock up bookings. It puts compelling factors into play to make Tesla cars irresistibly desirable.

- Attractive price

The most noticeable and irresistible aspect is the price of the Model 3. It starts from $35,000 before any incentives, which is a bargain when compared with the $75,000 for Tesla Model S.

- Software-backed design

Its design is equally compelling. A Tesla car by design is not a car—it is an iPhone on wheels. It is powered by software so it has neither heavy machinery nor too many moving parts, due to which it is lighter and is likely to have fewer breakdowns.

In the case of a breakdown, it does not have to be carted to a garage. Since it is powered by software, the problem can be diagnosed remotely and a software patch can be sent over the internet to rectify it. This drives down maintenance cost.

These benefits—convenience and time saving—are extremely desirable for millennials who are cash rich and time poor and are willing to spend cash to save time and get convenience. The lower cost of ownership is a bonus.

The brand marketing strategy

Yet another factor that has played a stellar role in Tesla capturing the imagination of customers is the way it markets itself. Take its showrooms, called Tesla Stores. They are designed not for selling the product—cars—but for building a brand. Tesla wishes to engage with people who walk into the stores and introduce them to the wonders of its technology by offering them interactive screens devoted to four major themes:

- Safety

- Auto-pilot features

- The company’s battery charging network

- Technology which powers Tesla

Its stores are more about the experience—about the wonder of its technology and quality of its products and less about selling it on the spot.

What is the consumer insight behind this strategy? The new way of selling a product is not to sell, but inform and educate customers about the brand, believing that a well-informed customer is likely to take decisions in the brand’s favour.

By the way, in addition to the interactive screens, Tesla has a range of Tesla gear (merchandise) ranging from t-shirts to tote bags and driving gloves. What does Tesla achieve by promoting its gear? Tesla desires to gradually create a brand image, not of an automobile, but of luxury that is an integral part of people’s lives.

How green is Tesla?

Now let us pose an inconvenient question. Is Tesla—and EVs in general—really as clean and green as it is perceived to be? The answer may lie in the grey zone.

It is an EV and is powered by battery and not fossil fuel. Therefore, while running, it does not spew carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide and other pollutants.

But if you take a closer look at Tesla’s Product Life Cycle Assessment, the picture turns grey. (Product Life Cycle Assessment assesses the environmental impact at all stages of a product’s life from cradle to grave—from raw material extraction, manufacturing, to its use and maintenance, to its disposal at the end of its useful life.)

Let’s start with the Model 3’s battery. It gives the car a range of 215 miles per charge. Therefore the battery has to be frequently charged by plugging into the local electricity grid and at the end of its useful life it has to be disposed of.

To deliver great performance, the battery has to be able to store large quantities of energy without adding weight. To achieve this, Tesla uses lithium, a rare element which is both superlight and a superconductor, in its batteries.

The problem with using lithium is it is a rare earth element—it is found in fewer parts of the earth and in small quantities. Therefore, to extract even a small quantity of lithium requires deep and extensive mining, which causes disproportionate damage to the local environment.

While the batteries are in use, they need to be frequently charged by plugging into the local electricity grid. If the power plant which feeds the grid is coal-fired, it—and indirectly the battery—is causing pollution.

In India, 62% of power generated is from coal-based power plants. This figure is not likely to reduce in the foreseeable future, because we are blessed with one of the largest coal reserves in the world.

When the Model 3 runs on Indian roads, it will be recharged by predominantly coal-based electricity. Therefore its carbon footprint in India will be high based on Product Life Cycle Assessment.

What about Asia? Here 59% of power is coal-based. Even in the US 38% of power is coal-based.

Finally, when the useful life of the battery is over, how will it be disposed of? Will they be efficiently recycled to extract the rare earth elements or will they be dumped in land-fills?

At the moment, the recycling ecosystem for batteries is weak given the small quantity of batteries that are in use and which come up for recycling. Therefore the recycling is being done by Tesla itself. But as EVs become a preferred way of transportation, many more batteries will come up for recycling. This will lead to a large-scale ecosystem for recycling batteries and the safe disposal of what is left over. Till then the harm that these batteries will cause to the environment could be significant.

Bottom line

The Model 3 still scores as an environment-friendly option. Among the cars currently available, it can be counted among the cleanest and greenest options—despite the carbon footprints being generated upstream (sourcing of raw materials and manufacturing) and downstream (during charging and battery disposal).

Of course, if the power plant uses renewable energy, Tesla will live up much better to the image it has created among its brand advocates. Alas, this option does not rest with Tesla.

But Tesla is not leaving that to chance. Last year it introduced Powerwall, a home battery that charges using electricity generated from rooftop solar panels. This would ensure that a Tesla owner can charge her car in her garage. Tesla is also working with government agencies and organizations in Europe and China to install public charging stations.

If Tesla can successfully execute this strategy, it will move closer to delivering on its promise of providing clean transportation.

[Update: This article was updated on May 2 to include information on Tesla’s solar-powered home battery Powerwall and public charging stations]

Brand Factory: Do deep discount stores have a future?

[Photograph: Outer Ring Road Apartments Brand Factory by Amol Gaitonde under Creative Commons]

Discount chain store Brand Factory is hoping to benefit from the new e-commerce regulations that prevent online marketplaces from influencing the price of products on their platforms.

Online players like Flipkart, Myntra (owned by Flipkart), Jabong, Snapdeal, Amazon and others which were offering deep discounts to attract customers would have to stop this strategy. As a result, the price of their merchandise would increase.

Brand Factory is anticipating that customers, weaned on deep discounts, would gravitate towards its stores. It has therefore adopted an aggressive posture to make this a reality, but I have reservations that this will work.

The background

Brand Factory, promoted by the Kishore Biyani-led Future Lifestyle Fashions (FLF), is an offline discount chain store. It was started in 2006 and has a presence in 20 cities where it runs 46 stores. It has tie-ups with over 200 brands, many of them marquee brands like Nike, Levi’s, United Colors of Benetton, Puma and more.

FLF also operates Central, a chain of department stores located in cities across India. It too offers sale, on an average, two times a year. Brand Factory plays a crucial role in ensuring that Central has fresh stock—leftover, non-moving and damaged stock is moved to Brand Factory to be liquidated by offering steep discounts. Therefore Central and Brand Factory operate in a symbiotic manner, one format helping the other.

Why Brand Factory’s discounts strategy is flawed

I have reservations for the following reasons:

- Value proposition: The deep discounts, ranging from 20 – 70%, are compelling for discount seekers and young upwardly mobile people who aspire for these brands but do not have disposable income. It also acts as a bridge to get non-brand users to graduate to fashion brands.

But there’s a drawback. Customers will come to the stores as long as the discounts are best in town. As soon as a competitor offers better discounts, they are likely to shift loyalty.

Recent events seem to support this view. Flipkart, Myntra, Snapdeal, Jabong and others attracted customers in droves predominantly by advertising the deals (deep discounts) and building a customer base of millions of buyers. Unfortunately, the loyalty was not to them but to the discounts they offered. Now that they have to stop offering steep discounts, their sales may head south.

Of course, there is a crucial difference between e-commerce companies’ strategy and Brand Factory’s. The former funded part of the deep discounts from their own pockets, burning a hole in their profit and loss statements (P&L). The hole became bigger because they spent astronomical amounts advertising it. Brand Factory also offers deep discounts, but without burning a hole in its P&L, because it does not fund it—it merely passes on the discount it has obtained through smart sourcing and skilful negotiation.

However, it has not eliminated the disease from the root—the loyalty of its customers could be to the discount it offers and not to the brand. This has the power to cripple it.

- Competitor-obsessed: Brand Factory has to be competitor obsessed to ensure that no competitor offers better discounts. This means it always faces the competitor while its back is to customers. The world’s most admired and valuable companies are customer-obsessed. They keep their customers at the centre of their strategy and build a plan around serving them. That is what makes them successful over extended periods of time.

- Quality of merchandise: It will be driven by opportunistic buying of non-moving, leftover, damaged, odd sizes merchandise which a brand owner may be wanting to offload. Hence, the merchandise stocked at Brand Factory will not be what customers want but what the purchase team can procure at a deep discount.

- Business model: Brand Factory offers a choice of over 200 brands under one roof—like a department store. But department stores across the world are facing challenging times because a customer looking for, say, Nike shoes, would prefer to shop for it in a company-owned store where she can expect more options and a genuine Nike experience.

Similarly, many of the marquee brands Brand Factory houses also have company-owned stores, both online and physical stores, through which they sell their non-moving merchandise at deep discounts.

- Gross merchandise value (GMV): Brand Factory claims to have a GMV of Rs 4,000 crore. But is this the metric that it should be showcasing? Has not the mindless pursuit of GMV got many marquee e-commerce companies in hot water? GMV does not give an indication of the quality of sales—it measures the sales clocked, which can be “managed” by “buying” it, i.e. by offering irresistible discounts.

A timeless business axiom advises us that what gets measured gets done—if GMV is being measured then it will be pursued at all cost, leading to GMV myopia. Flipkart is experiencing the consequence of pursuing this metric at the cost of others.

Instead, Brand Factory should focus on customer-centric metrics: Net promotor score which measures brand advocacy, customer satisfaction score, repeat purchase rate, customer retention rate and referral rate. If these metrics are positive, it would indicate that customers are happy with the brand. As a result, the “outcomes”, or business parameters like revenue, margin etc. are most likely to be robust.

- Asset-heavy business model: In today’s on-demand economy (also referred to as sharing economy) it pays to operate an asset-light model. Brand Factory’s business model appears to be asset-heavy. It requires investment in setting up bricks-and-mortar stores as well as cash for buying merchandise.

- Operating in red ocean space: Brand Factory derives significant revenue from apparel brands—which operate in what is known as red ocean space, or crowded markets where the competition for market share is intense. Furthermore, the apparel industry is facing a problem of its own making. A majority of sales of even fresh stock takes place only when it is on sale. So, the apparel industry takes a steep price increase so that even after parting with eye-popping discounts multiple times a year, its bottom line is not severely dented. A dented brand image is the collateral damage. If the industry does not change its strategy, over time brand image will be so severely damaged that brand owners will not be in a position to take a price increase or pull in customers. Profit, which is already low, will sink further. Brand Factory’s profitability too will suffer as this scenario starts materializing.

What is the future of Brand Factory?

It may face the same future as e-commerce companies that “bought” revenue by offering deep discounts, burning a hole in their P&L.

The saving grace is that Brand Factory is not putting money from its own pocket to offer deep discounts.

Where will Brand Factory rock? Most likely in Tier 2 and 3 towns where marquee brands command aspirations but have not yet opened their own stores. In such towns, Brand Factory could be the only option for customers.

But even this is risky because “…by 2020, nearly half the internet users would be from rural areas and tier-4 towns (with population under 100,000),” Mint reports. People residing here too will opt for online company-promoted stores to get deals and bargains, bringing Brand Factory’s reason for existence under scrutiny.

What Brand Factory ought to do

Brand Factory could take inspiration from Walmart and pivot its business model to make it more robust, enduring and profitable.

Walmart ranked No. 1 in the Fortune 500 list (2015) and clocked a revenue of $482 billion. It grew by offering “Everyday Low Price” (EDLP), but by 2007 it had replaced this promise with “Save money. Live better.”

Why? Because price is a feature and shoppers do not buy features, they buy benefits. In neuro marketing terms, features such as price appeal to the neo cortex part of the human brain, where rational and analytic thinking reside. But when a company offers a benefit, it touches the limbic part of the brain where emotion and behaviour reside. When a brand touches emotions, a person’s behaviour towards the brand changes positively. Once this happens, the brand can offer rational reasons for buying—price and discount.

Bottom line

It would be prudent for Brand Factory to move away from offering a feature (low price) and graduate to promising a benefit which will appeal to the customer’s self-interest. This will help Brand Factory graduate from merely having a transactional relationship with its customers towards nurturing a more enduring relationship with them.