[People dining at the many restaurants across the Duke’s Palace in Dijon]

In some ways, the genesis of my annual Europe sojourn this year was laid by the banks of the river Ill in Strasbourg in July last year. Strasbourg, the capital of France’s Alsace region, is famed for its white wine. On a warm summer evening, as the sun set over Strasbourg, I found myself a table at L’Alsace a Boire, one of the city’s hippest wine bars, and quaffed glass upon glass of the region’s best-known grape varietals—rieslings, gewurtzraminer, sylvaner and Klevener de Heiligenstein. The day before I had visited the Cave Historique des Hospices de Strasbourg, a 14th century wine cellar that was restored to its pristine glory by a collective of 22 Alsace wineries. Here, an oenologist made me taste wine straight from an oak barrel—not something I had expected on a visit to the city’s civil hospital (I wrote about it here). I had enjoyed the experience so much that I decided, then and there, that in 2025 I’d return to France to explore some of its other famed wine regions.

And so on August 1, I landed in Dijon, capital of the Burgundy region, known for producing some of the world’s most prestigious white and red wines. That was to be followed by a four-night stay in Lyon, capital of the Rhone-Alpes region, a gateway to the Beaujolais wineries and France’s fourth-largest city after Paris, Marseilles and Toulouse. (Sidenote: the Lyonnaise believe they’re larger than Toulouse but the Toulousains think otherwise).

For a majority of Indian tourists, a trip to France would include stays in Paris and the southern part of the country. I’d already been to Paris in 2024 and the idea of getting roasted in scorching heat, even if it was on the French Riviera, didn’t particularly appeal to me.

When I was planning this trip sitting in the furnace that New Delhi becomes in May, I had some ideas which, in retrospect, seemed a bit too ambitious. The initial plan was to spend two days exploring Dijon and on the remaining two days, take day trips to explore Burgundy’s wineries. I’d planned to replicate this in Lyon too—two days for the city, two for winery-hopping in Beaujolais. But as the famous saying goes, the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry. I’ll come to that in a bit.

Dijon: Mecca of Gastronomy and Wine

From the moment I landed in Dijon, I fell in love with it. Just the way the city looked was mesmerising. Cobblestoned streets, timber-framed houses, ornate facades, sloping red rooftops and an imposing Church of Notre Dame—it felt like walking through a picture-perfect postcard.

Since it was summer, restaurants and bars had al fresco tables on the streets, each packed with tourists from across the world. This mass congregation of nationalities had one singular purpose: to sample the best cuisine and wine the capital of Burgundy had on offer. The authorities governing Dijon seemed all too aware about this too. Nearly every touristy activity that had nothing to do with food or wine was either free or priced very reasonably. For instance, the city has five museums dedicated to archeology, fine arts, Burgundian life, sacred arts and to the artist Francois Rude. Entry to all of them is free. A 72-hour unlimited travel pass on Dijon’s excellent tram system that encircles the city costs just 9 Euros. The signal from the city was clear: spend the money saved on food and drink. After all, UNESCO added the “gastronomic meal of the French” to its Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2010. And Dijon is as French as it gets.

[Dijon rooftops and the vineyards beyond as seen from the Philip the Good tower]

Over the last decade-and-a-half, I’ve had the good fortune of visiting cities that are famed for their food. New York is home to possibly every cuisine from every country on the planet. It is almost impossible to have a mediocre meal in Florence, Naples or Rome. Some of the best Thai food is available in Prague and Berlin is home to the most melt-in-the-mouth doner kebabs. But what distinguishes Dijon from these cities is that it has tied its whole identity to gastronomy and wine. The Cite Internationale de la Gastronomy et du Vin is, quite literally, a shining example of this. From the outside, the all-glass facade of the building might make visitors think that it’s an office complex. But once inside, it reveals its true character as a homage to French gastronomy. There’s a bookshop, a movie hall, an immersive exhibition centre and workshop spaces, all centered around food and wine. In case this wasn’t enough of a tribute there is also a restaurant serving—what else—French food.

Snail-paced and Proud of It

As in much of France (and, to some extent, Italy), lunch or dinner is a sacred activity that cannot be hurried. At a brasserie, diners are expected to ritualistically order a three-course meal, preferably with a glass (or, if your capacity permits, a full bottle of wine). A typical entree (first course) in Burgundy is a portion of the famed escargots—snails cooked in-shell in butter garlic sauce. You can choose a small portion of six pieces or a larger one of 12 pieces. Either way, it’ll be a novel dining experience as you have to hold the shell with special tongs in one hand and, with the other, use a small fork to scoop out the meat. After a couple of clumsy initial attempts, I did manage to eat my escargots though with questionable finesse.

[A portion of escargots and creme brulee—the best dish to cap a three-course French meal at the Bouillon Notre Dame in Dijon]

The plats (second course) is the main course which in Burgundy is a boeuf bourguignon—beef cooked in a sauce that’s made of red wine, beef stock, onions and garlic, till it’s so tender it starts falling apart.

The dessert (third course) was either a creme brulee or a platter of fromage—cheese—that I wolfed down with the aforementioned wine. At about 35 Euros per head, the meal might seem a bit expensive but was a very filling one. After a three-course lunch or dinner, I almost never felt hungry through the rest of the day or night. Of course, at each of these meals the star of the show was a glass or a carafe of Burgundy wine.

[Palace of the Dukes and Estates of Burgundy, Dijon]

Lost in Appellation

However, choosing which wine to drink at lunch or dinner or at sunset wasn’t easy. All I knew was that Burgundy was known for Pinot Noir (red) and Chardonnay (white). But it wasn’t as simple as that. The trick lay in understanding the four-tiered appellation system used to categorise Burgundy wines. At the bottom, is the regional appellation. So, if a wine bottle says “Bourgignon/Burgundy” it means that grapes from different parts of the region have been used to make the wine. One level above is the commune appellation to indicate the village/commune of provenance—such as Pommard, Meursault, Chablis, Puilly-Fousse etc. Above them are the premier crus—wines made in one of the 640 exceptional plots of the aforementioned villages. Finally, there are the Grand Crus—wines from 33 plots that are so superior, they get their own appellation. These include Romanee-Conti and Montrachet. The idea behind the classification system is to highlight the distinctive terroir—“the symbiosis of grapes, soil, climate, vineyard placement, and human touch all rolled into one”, according to Wine Folly. To my under-exposed palate and very sensitive wallet, this hierarchy meant just one thing: stick to the regional or village appellation wines and forget about the Crus. There was no way I could afford the 4,200 Euros on a bottle of Romanee Conti that I saw at a wine bar in the neighbouring city of Beaune where I’d gone for a day trip.

[Wines on sale at the Les Clos Vivants store in Dijon]

Other than the appellation system, high demand and low supply is the other reason why Burgundy wines are more expensive than others. France has about 775,000 hectares of vineyards, of which only 30,000 hectares constitute the Burgundy region. “Thus, for 200 million bottles produced each year in Burgundy, 650 million are put on the market for Bordeaux and 465 million for the Rhone Valley,” according to La Cave Eclairee, an online wine retailer in France. From my own experience, I can attest that the high price is in line with the quality of wine that I consumed.

Remember the plans of mice and men—the ones that go awry? I had planned a day trip to Beaune. The start to the day had been disappointing. My train got delayed by a few minutes and I couldn’t make it in time for a guided tour of a Burgundy vineyard that I had pre-booked. The tour, scheduled to start at 11am, had already been delayed to accommodate me. But the train chugged into Beaune station only at 11.07AM. I ran to the tourism office from where the tour was supposed to begin. I got there, huffing and puffing, at around 11.20AM, but the group had left. I was both furious and upset because I’d been on the phone with the tour guide, constantly updating him about my arrival.

[Wines on display at the L'Arche Des Vins wine bar in Beaune]

Thankfully, the tour operating company understood my situation and refunded the fee. But the whole experience left me disappointed. To lift up my spirits I landed at L’Arche des Vines, a wine bar and retail store, and ordered a glass of Meursault white wine. It was unlike any other Chardonnay I’d tasted before—oaky, smoky and full-bodied. That was followed by a red wine—a 2023 Vosne-Romanee—bursting with red fruit flavours. My total bill for two glasses of wine? 39 Euros.

[The fabulous Meursault I had at L’Arche des Vins in Beaune]

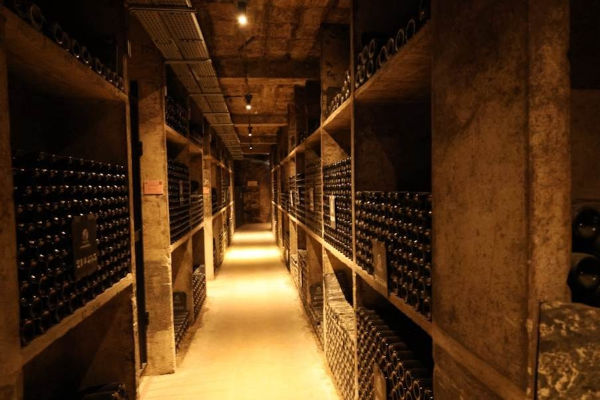

That I was in Burgundy and wouldn’t be able to visit a winery wasn’t something I was prepared to live with. A quick Google search revealed that Beaune was home to Patriarche, a winery founded in the 18th century. It wasn’t too far from the city centre, offered guided tours for 25 Euros per person and had 5km of cellars that visitors could walk through. After a quick doner kebab roll lunch on-the-go, I landed up at the Patriarche headquarters, ready for an hour-long walk through the cellars, followed by a tasting of six wines. What I expected from the tour was a repeat of my experience last year at the Moet et Chandon and Pommery champagne cellars in Reims and Eparnay.

[A corridor in the Patriarche cellar, stacked with wine bottles]

On those tours, a professional sommelier working with those champagne houses guided a group of us as we walked through dimly lit, chilled cellars, sharing interesting trivia and anecdotes. In comparison, the Patriarche tour was a bit of a disappointment. First, it was a self-guided tour. The winery had placed giant touch screens in different areas that visitors had to tap on. A few more taps later, short videos detailing the history of the winery. There was nobody to tell us interesting trivia or anecdotes. We just had to walk, tap a screen, watch a video, and walk again. Not quite what I was expecting. I’d have happily paid a little extra for a guide to enlighten us about Patriarche. The lack of a guide aside, it was fascinating to walk through those corridors, lined with art and quotes about wine. The final tasting was comprehensive with servers briefing visitors about the various appellations of Burgundy.

An Immovable Feast for the Eyes

Dijon isn’t just a feast for the stomach but also for the eyes. Just walking around the city, soaking in the sun, observing fellow tourists, admiring the architecture and encountering some of the city’s eccentricities felt therapeutic.

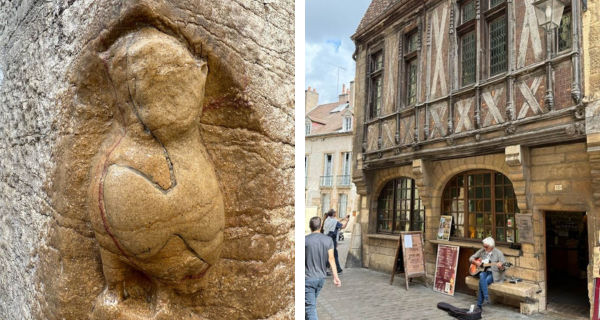

One of these quirks is the owl of Dijon, a statuette located on the chapel wall of the Church of Notre Dame, which serves as the city’s unofficial symbol. Legend has it that if you make a wish while touching the owl with your left hand, it will come true.

[From left: The Owl of Dijon—the city’s unofficial mascot; The Maison Milliere—Restaurant Boutique Bar a vin, a 15th century building that’s considered one of the oldest in Dijon]

A few minutes away is the Liberation Square, a semi-circular public square, flanked by the Grand Palace of the Dukes of Burgundy on one side and a row of open-air restaurants and bars on the other. As night falls on Dijon, the square, palace and surrounding areas are illuminated and a cool breeze blows across the area, making it the perfect spot for a post-dinner nightcap. So beautiful was the sight that on my last two nights in the city, despite being dog tired after 12km-long walks, I just sat at the square admiring the lit up palace and soaking in the atmosphere. At 11PM, I reluctantly dragged myself back to the Airbnb, hastily packed my bags and prepared for my onward journey to Lyon.

The Many Layered Histories of Lyon

From the moment I arrived at Lyon Part-Dieu, the city’s central train station, it became abundantly clear to me that I was in a big city. As I deboarded the train and made my way out of the station, all I could see was vast swathes of people, walking in and out of Lyon Part-Dieu. For a city that claims to be France’s fourth largest, the size of the crowds took me by surprise. Then again, I reminded myself, this is peak holiday season in Europe and boarded the tram to the city’s Perrache neighbourhood where my hotel was located.

[Croix-Rousse as seen from the Fouviere Hill]

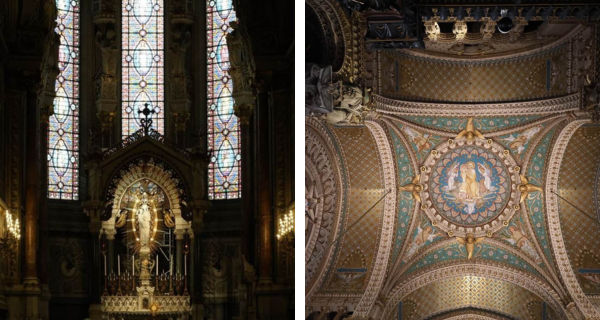

The Perrache is part of Lyon’s Pres’quile, an “almost island” in French, a peninsula that is in many ways the beating heart of the city. Its northernmost point is the Croix-Rousse Hill, once home to the thriving silk industry and its southernmost point is La Confluence where the rivers Rhone and Soane converge. In between lie museums, restaurants, residences, bars, public squares, tram and metro lines. To its east lies Vieux Lyon, the Renaissance-era old city dotted with bouchons (traditional Lyonnaise restaurants), galleries and souvenir stores. It sits at the foot of the Fouviere hill, home to a majestic Basilica dedicated to the Virgin Mary and two Roman theatres dating back to 43 BC.

[Inside the Basilica dedicated to Virgin Mary. From left: Virgin Mary; the church ceiling]

To be honest, I only knew of Lyon as a city that is just half an hour away from the Beaujolais wine region by train. It wasn’t until I reached the city’s tourism office that I realised how rich and layered a city it is, brimming with history and culture. It helps that the city authorities have introduced a Lyon City Card that allows tourists unlimited travel on public transport, free entry to museums and a complimentary hour-long river cruise along the Soane. Since I was in the city for four nights, I bought a 96-hour pass at my hotel for 68 Euros (there are 24, 48 and 72-hour options also) and headed straight for the river cruise.

[A view of the buildings of Lyon from the boat cruise. Note the Italian influence on the facade]

The journey is like a time capsule through the city’s history, from the time it was a part of the Roman Empire, to its role in the Second World War and now as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. My only quibble about the bilingual cruise was that our guide was more fluent in French than in English so I couldn’t understand a lot of the trivia he shared. However, two fascinating nuggets stayed in my mind.

The first was about Klaus Barbie, a Schutzstaffel officer who is said to have personally tortured Jews, as head of the Gestapo in Lyon. After the Second World War, US intelligence used him as an informant to keep them in the loop about communist activities and, in 1951, helped him escape to Bolivia where he lived as Klaus Altman until 1983. Known as “the Butcher of Lyon”, Barbie was eventually extradited back to the city of his sins that year and tried for his crimes. In 1987, he was sentenced to life in prison where he died in 1991.

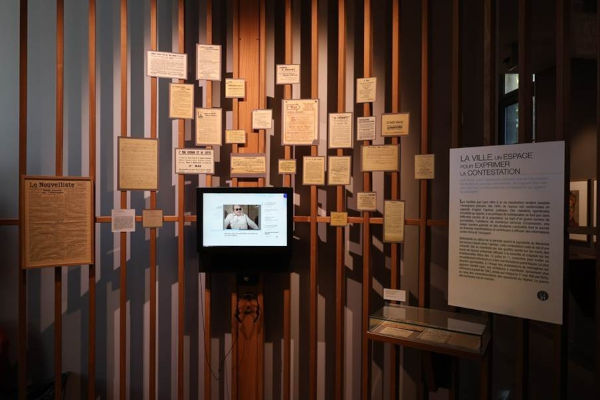

[Clandestine newspapers and pamphlets published by members of the French Resistance to counter Nazi propaganda at the Resistance Centre in Lyon]

As the air-conditioned boat moved northwards, it passed by the Ile de Barbe, a small island in the middle of the Soane. This was the second nugget that registered with me. It was once home to an abbey built in the 5th century—the first monastic establishment in the region—which was unfortunately destroyed by Protestant troops in 1562, according to the city’s official history. Today, part of the island is open to the public while the other half is private property that hosts Les Suites I’le Barbe, a five-star hotel that promises its guests tranquility amidst the hustle and bustle of the city.

Inside Story: The Tales that Traboules Tell

[The famous Mur de Canuts, a gigantic mural, in the Croix-Rousse Area]

The following day, I signed up for a guided walking tour of Vieux Lyon with Aidan, a local resident who routinely conducts these activities with his father Ryan. The excursion started at the sprawling Place Bellecour, the largest pedestrian-only public square in Europe, and took us to the Basilica, the Roman theatres, the narrow streets of the old city, and introduced the group to the concept of traboules—secret passageways that connect two streets in the city through buildings.

[The Roman theatre on Fouviere Hill]

The traboules were used extensively first in the 19th century by silk traders to carry goods from their workshops to textile merchants. Since streets in the Vieux Lyon area run parallel to the Soane river, workers had to take long detours to complete their journey. Traboules were created as shortcuts to overcome these logistical hurdles. They came in handy during the Second World War too, when members of the French Resistance used them as secret passageways and hideouts.

[Looking up from the courtyard of a traboule in Vieux Lyon]

According to Lyon Tourism, there are 500 traboules in the city—200 in the Vieux Lyon Area, 160 on the slopes of Croix-Rousse and 130 on the Presqu’ile. However, only 80 are open to the public. Of these, the most famous is the passageway that connects Place Colbert, Montee Saint-Sebastien and Rue Imbert-Colomes in the Croix Rousse area via three entrances and whose courtyard is home to a beautiful six-floor stairway.

[Part of the famous six-storey stairway that visitors spot after crossing the famous traboule in Croix-Rousse]

As we walked through the traboules of Vieux Lyon, Aidan requested us to speak as softly as possible. In buildings above these passageways are residences, often subsidised by the government. He also let us in on a secret: a traboule can be identified by a black wrought iron arch atop the main door. All visitors have to do is press a button, push the door and walk in (unless of course the door is marked “private”). For the Lyonnaise, the traboule system is a hidden gem that only they know about and can navigate with ease. Nobody else—not even Google Maps—can help outsiders navigate them.

Reality Bites

After the two-and-a-half hour walk that ended at lunch hour, Aidan suggested that we feast on traditional Lyonnaise cuisine at a bouchon. The suggestion came with two friendly warnings: first, that Lyonnaise food isn’t for the faint-hearted and second, there is nothing vegetarian about them. Dishes include Andouillette, a sausage made of pork intestines, Sabodet, another sausage made with the pork head, snout and ears, Tete de veau (poached calf’s head) and my personal favourite, Saucisson de Lyon brioche (sausage encased in brioche bread). A bouchon isn’t a registered trademark so there are plenty of restaurants masquerading as one. As a counter move, the original ones have come together to form Les Bouchons Lyonnaise, an association that distinguishes them from those that only claim to be bouchons but are not. Visitors can use the website to search for an authentic one in the zip code they’re in or look for the “hatted man” symbol at the entrance.

[A pie filled with pig’s head sausage, cheese and bread, served with bread and wine at a traditional bouchon]

My travels through the time capsule that Lyon is, came to an abrupt halt on the penultimate day of my stay there. After a long walk through the Croix-Rousse hill, soaking in the public art and typical French architecture, I returned to the city centre where the reality of being a tourist in France hit hard. As I was walking towards a store, a teenage girl screamed for help and started asking me for directions to the nearest metro stop in French. A group of her friends soon joined her and all of them started speaking to me in a language I barely understood. After a few minutes of failed communication, we all went our separate ways. Instinctively, I checked if all my belongings were with me and realised that my wallet was missing. That’s when the penny dropped: the request for help was a ploy to distract me and nick my wallet. Thankfully, French police personnel were nearby and, just as they were noting down my complaint, the thieves started using my credit cards at a tobacco store. The cops alerted their colleagues in the area who swooped down on the store, apprehended the girls and reunited me with my wallet. The following day, my last in Lyon, was reserved for a trip to Beaujolais. Instead, I found myself at a police station lodging a formal complaint about wallet theft and fraudulent card transactions.

The unfortunate incident aside, my visit to Lyon and, to some extent, Dijon, was an eye-opener that taught me two important lessons. First, cities are not just mere gateways to other regions; they contain within them long histories and layered stories that can be as enjoyable as a visit to a vineyard. Second, beneath the eye-pleasing aesthetics and culinary delights lies a brutal reality: petty crime in France is rampant. Even if your instincts tell you otherwise, don’t fall for help requests and keep your belongings in a bag. Unless you enjoy the company of the very helpful French police.

Travel Tips

[An evening walk in the Vieux Lyon neighbourhood where bars and restaurants were buzzing with diners]

1. Rent a car: If you’d like to visit wineries in Burgundy, rent a car or an electric bike for a few days and drive around the region. Public transport in the small towns and communes is patchy and unreliable—best to make your own arrangements.

2. Budget for food and wine: As a cousin of mine said, “Burgundy is like the Rolls-Royce of the wine world.” It follows, then, that food and wine in Dijon will be a tad more expensive than, say, in Paris. Though it’s the capital of Burgundy, Dijon is a small city and has only a limited number of restaurants and bars. Be prepared to fork out approximately 35 Euros for a three-course meal at a brasserie. Alternatively, you can choose to splurge on the wine and grab a sandwich (7-8 Euros) from one of the many boulangeries that dot the city.

3. Book winery tours: If you’d like to visit specific wineries in Burgundy, write to them or book a slot on their website. Summer is peak travel season in Europe and wineries are inundated with requests for a tour, especially in Burgundy.

4. Tours from Beaune: Most group tours to wineries and vineyards start from Beaune, a small town near Dijon well-connected by train (average journey time is about 15 minutes) and Flixbus (average journey time is 30 minutes). Make sure to book your tickets and tour seats in advance and pray that trains don’t get delayed.

5. Secure your wallet: Do not keep your wallet in the back pocket of your trousers or shorts. It belongs in a satchel/crossbody bag. Do not keep all your credit cards and foreign exchange cards together. And yes, keep the absolute minimum amount of cash. France is notorious for petty crime.

6. Plan your day by the weather: Lyon gets very warm during the summer so it’s best to be indoors between 12 and 5pm. Don’t worry about losing out on time; the sun doesn’t set before 8PM; even if you step out in the evening, there’ll be plenty of sunshine.

7. Traveling with Lyon: As a tourist, the Lyon City Card is a must-have. It allows unlimited rides on all public transport for 24/48/72/96 hours, so you don’t have to worry about fares. Plus, entry to most museums and an hour-long boat cruise is free. Like almost everything else in Europe, you can buy the city card online. Alternatively, you can buy it at the city’s tourism office or at your hotel at check-in.

8. If you do get pickpocketed: Finally, if your wallet does get nicked and your cards are misused, file a formal complaint with the local police and forward it to the banks immediately so they can reverse/cancel transactions. Also lodge a complaint on the Centralized Public Grievance Redress And Monitoring System (CPGRAMS) portal. They will intervene with the banks too and chances of dispute resolution will be much higher.