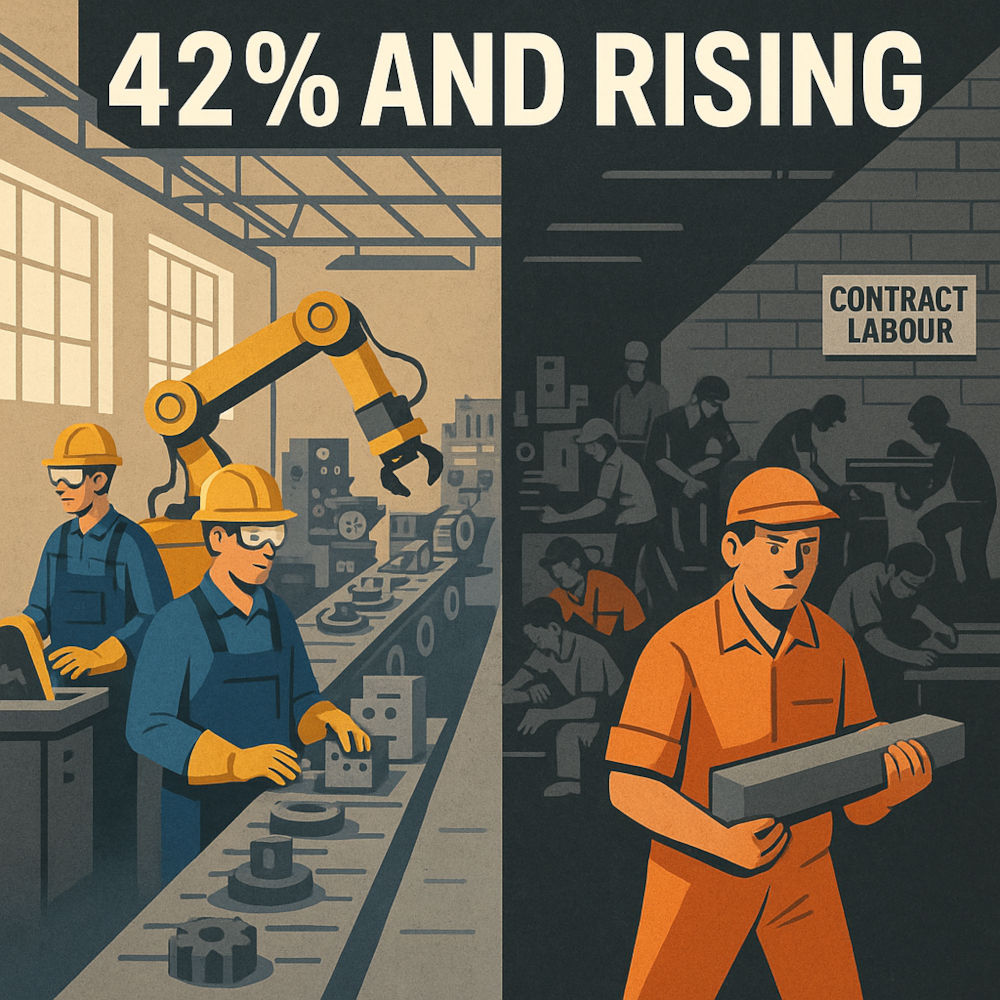

The latest Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) for 2023–24 carries a statistic that should stop every business leader in their tracks: 42% of the workforce in India’s organised manufacturing sector is now on contract. This is the highest level ever recorded — and it’s a number that will almost certainly grow in the years ahead.

Yet, despite its significance, this government-released data has barely made it to mainstream headlines. This quiet surge in precarious work tells a much bigger story about the future of manufacturing and the health of corporate India.

From Temporary Fix to Permanent Strategy

Over the past few decades, India has been on a rapid growth trajectory, seeking to attract investment and boost competitiveness. For years, investors and economists have pointed to India’s rigid labour laws as a barrier to growth. Initially, companies turned to contract labour as a temporary solution — to meet short-term demand spikes or to staff time-bound projects. This was understandable during periods of economic downturn, such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, what was once an exception has now become the norm. Today, contract workers and fixed-term employees are deployed even for core, regular and perennial roles. Fixed Term Employment (FTE), reintroduced in 2017 to address genuine short-term needs, is now being widely used for regular work, blurring its original intent.

Third-party staffing agencies have added another layer of distance between companies and the workers who power their factories. While these agencies are often better on compliance than traditional contractors, their very presence weakens accountability and engagement. The result is a workforce model in which the employer-employee relationship has become increasingly transactional and fragile.

This drift is no longer confined to MSMEs or struggling units. Even India’s most admired and financially strong companies now depend on this model. What began as a tool for flexibility has become a structural feature of India’s industrial landscape.

The Divide on the Factory Floor

The human impact of this shift is visible in stark and often troubling ways. Contract workers typically earn 30–40% less than permanent employees for the same work and many remain pegged at minimum wages for years. While statutory requirements such as PF and ESI are met, many workers are excluded from paid leave, welfare facilities, and other benefits. In some cases, even payments for overtime, bonuses, and gratuity never reach the workers, despite being paid by the company to the contractor.

“These may appear like operational details, but they cut deep. They create a cultural fault line that can destabilise even the most efficient organisations.”

The divide shows up symbolically as well. Separate canteens, entry gates and uniforms. Invitations to annual day celebrations and family events restricted to permanent employees. Even in offices, disparities are evident in recognition programmes, salaries, and identity badges. In locations where companies provide transportation, the quality of buses is often different for contract workers and regular staff.

These may appear like operational details, but they cut deep. They directly affect motivation, morale and, over time, productivity. They create a cultural fault line that can destabilise even the most efficient organisations.

Lessons From the Past

It’s not as if this divide has been free of repercussions. There have been flashpoints where underlying tensions boiled over. The most dramatic example remains the Maruti Suzuki violence of 2012 at the Manesar plant, when simmering anger over disparities between permanent and contract workers erupted into violence, leaving a senior manager dead and many injured.

This was more than a labour law failure — it was a cultural and leadership failure.

In the immediate aftermath, companies rushed to install CCTV cameras, stricter security measures and PR-driven engagement programmes. But the deeper structural drivers — unequal pay, unequal treatment, and exclusion — were never truly addressed.

Have we truly learned anything in the past 13 years, or are we simply waiting for history to repeat itself?

Why This Should Worry Us

This quiet drift toward precarity should deeply concern business leaders. The risks span three critical dimensions: legal, organisational and societal.

Legal and Ethical Risks

Recent Supreme Court judgments, such as Jagoo vs Union of India (December 2024) and Shripal vs Nagar Nigam (2025), have strongly emphasised fairness, equity and adherence to constitutional principles in employment practices. They explicitly caution against the misuse of temporary contracts to evade obligations toward employees.

Despite this, widespread violations of “equal pay for equal work” persist. Companies are sliding into a legal grey zone, risking litigation and penalties, with the Principal Employer ultimately accountable for lapses by contractors.

Organisational Health Risks

Many companies conduct employee health surveys to track engagement and morale, but contract workers — who may form half the workforce — are routinely excluded.

Safety standards are inconsistent. Contract workers are often left out of structured training, directly affecting accident rates and productivity. The presence of a two-tier workforce undermines trust and collaboration, while lack of investment in upskilling erodes innovation and long-term competitiveness.

Over time, this weakens leadership credibility, both internally and externally.

Societal Risks

“The absence of visible unrest today should not be mistaken for stability. Tensions that build silently can erupt suddenly — with devastating consequences.”

India’s challenge is not merely to create more jobs, but to create good jobs.

Insecure, low-paying roles create what experts call “employed poverty” — trapping workers in a cycle of stagnation and frustration. This fuels resentment, saps aspirations, and risks spilling over into mass indiscipline or law-and-order crises.

The absence of visible unrest today should not be mistaken for stability. As we saw at Manesar, tensions that build silently can erupt suddenly, with devastating consequences for companies and communities alike.

The Paradox of ‘Formal’ Job Creation

The government’s recently announced Employment Linked Incentive (ELI) scheme, with an outlay of Rs 1 lakh crore, aims to create 3.5 crore formal jobs. At first glance, this seems like a progressive step.

But under current definitions, any job with PF coverage qualifies as “formal” — including contract positions. This means low-paying, insecure roles will boost the formal job numbers, giving policymakers and the public a false sense of progress.

Quantity may rise while quality stagnates. Would business leaders and policymakers be satisfied with applying a “band-aid” to the employment issue, or will they measure what truly matters: stability, skill development, and upward mobility?

Why Business Leaders Must Act Now

For business leaders, this isn’t just an HR issue. It’s a strategic challenge.

Global investors and supply chain partners are scrutinising labour practices more closely than ever. ESG reporting norms for listed companies require disclosures on workforce treatment and fairness. Failing to “walk the talk” can damage reputations and access to capital.

Operationally, excluding contract workers from training and engagement directly impacts safety and productivity. Legally, courts and regulators are signalling stricter enforcement ahead. Waiting for a crisis could mean sudden disruptions, penalties, and lasting reputational harm.

A Path Forward

The path forward will require courage and foresight. Leaders can start by:

-

Reviewing and auditing their reliance on contract labour, focusing on productivity and value creation rather than low-cost headcount.

-

Integrating contract workers into safety, training, and engagement programmes — recognising that a safer, better-skilled workforce benefits everyone.

-

Working with policymakers to shape fair, sustainable frameworks instead of waiting for regulation to be imposed from outside.

A Moment of Choice

The 42% figure is not just a statistic. It is a warning signal about the direction in which India’s manufacturing workforce is heading.

Business leaders now face a choice: to lead with foresight and build workplaces that are both agile and fair, or to look away until unrest and regulation force their hand.

If they choose the former, they will not only prevent future crises but also strengthen India’s competitiveness and social stability. If they choose the latter, history will repeat itself — with consequences none of us can afford.

The quiet drift toward precarity will not stay quiet forever. Whether we act now or later will determine the future of India’s manufacturing story — and of India Inc itself.

Dig Deeper

Modern Times redux: Is the government’s Make in India programme creating a system where a large section of workers in manufacturing could find themselves trapped in low wage jobs with no future? (May 29, 2023, Read time: 4 mins)

Suspending labour laws means paving a road to nowhere: Far from bringing in new business, the wholescale suspension of labour laws by some states poses a real danger of unleashing mistrust among factory workers. For the move is fair neither to workers nor to employers. (May 11, 2020, Read time: 11 mins)

The used and discarded workers of India: Many continue to congratulate state governments for being bold in withdrawing constitutional protections of Indian workers, apparently to attract foreign investors. They’re missing the facts on the ground. What will convince them to open their hearts to the plight of millions of citizens? (May 18, 2020. Read time: 5 mins

VIVEK PATWARDHAN on Sep 14, 2025 4:25 p.m. said

Congratulations Founding Fuel as well as to Mr Vineet Kaul for an excellent article on this issue of great importance. I present my views on the subject which only elaborate various facets of the contract labour issue.

The situation on the ground is something to worry about. First, we should not speak only about contract workers. We should speak about contingent workforce. That means we include a larger group of exploited workers. Contingent workforce includes trainees, apprentices, temporary employees, and contract employees at various levels. Their problems are identical.

Second, our Government, irrespective of parties which run it, simply does not implement its own laws. If laws were implemented strictly, the contingent workforce problem would lose its magnitude and severity.

Third, the unions have lost their teeth. Political leaders have deserted unions and they are replaced by ‘internal leaders’ who neither have the understanding of workers’ rights nor the skill and will to fight for it.

The Government came out with NEEM or National Employment Enhancement Mission which was launched in 2013. It allowed employers to engage contingent workforce without any pangs of conscience. It was a scheme which formalized exploitation. A writ petition was filed in the High Court. The Government withdrew the scheme.

There is a scheme launched by a private Institute which had the approval of the Government. There was outright exploitation allowed under this scheme. If you go to my YouTube channel you will find video recordings of workers who were so exploited. Companies supplying temporary staffing exploited the situation.

I have in my book ‘People at Work’ wrote about exploitation of contract workers in detail. The fact is that not just employees at lower level of pyramid like receptionists but even HR Managers at the entry level are getting appointed on contract.

The manpower supply companies like Teamlease have been able to influence the Government policies or at least GRs. Their influence is growing and Manish Sabharwal persuasively champions labour law reforms. He is Wharton educated, and is highly skilled at this art. But I wonder if he has seen the ground level reality.

People who stand at the road-corners, the casual workers, waiting for a contractor to take them and give them a day’s work are so large in numbers that they accept any wage, even if it is not (more often than not it is not!) the minimum wages.

When some of these persons are absorbed as ‘Contract workers’ in factories, they are happy that they now get to work 26 days on a month. And they usually get the minimum wage which is actually subsistence wage. They know that they keep the job as long as supervisor is happy. This is why they do any kind of work, quite unlike permanent workers who refuse to do the work which they think is not ‘their job.’ Employers like this flexibility.

When these contract workers get absorbed as permanent workers (and such chances are remote) they watch the exploitation of contract labour brothers without a whimper of protest. They connive silently (or have to connive) in the exploitation process.

It is convenient for all of us to ignore the problem because if we know the details we face a bigger question which haunts us and for which we have no answer – ‘What kind of Society we are building?’

Before I sign off I would like to mention an interesting case. Thermax employed only contract workers at its factory near Baroda. Contractors became powerful there and there was big protests. Thermax then completely changed its way and have created a process by which employees are regularly absorbed in permanent service and it is working exceptionally well. This means contingent workforce problem can be solved at the enterprise level by the employers – if they have the will!

Vivek Patwardhan