Last month, Brazil’s Attorney General’s Office delivered an extrajudicial notice to Meta, demanding that the company “immediately remove artificial intelligence robots that simulate profiles with childlike language and appearance and are allowed to engage in sexually explicit dialogue.”

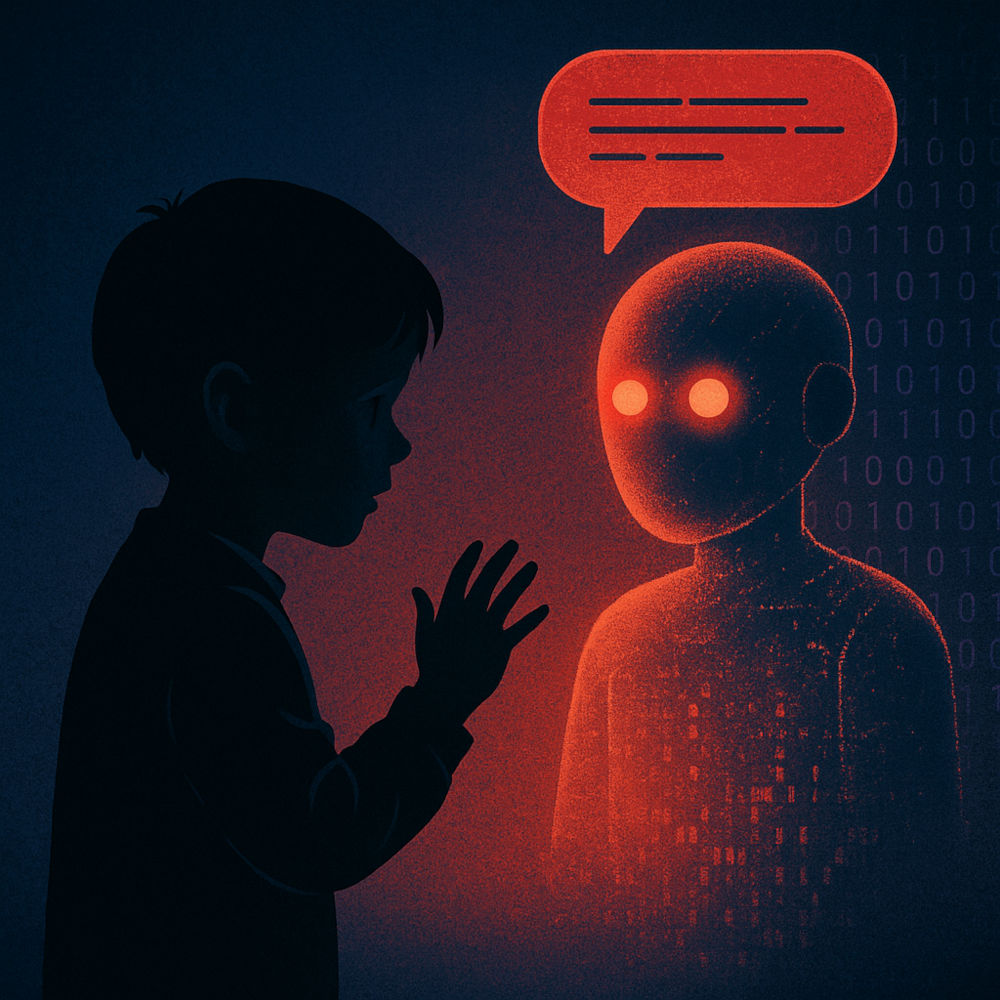

The Attorney General said these bots, created via Meta’s AI Studio, “promote the eroticization of children” and highlighted a chilling fact: there are no effective age filters preventing teenagers aged 13-18 from accessing such content. This was not a hypothetical fear. Public prosecutors cited investigative reports showing explicit conversations between bots posing as minors and users.

Two weeks ago, around mid-September, Brazilian President Lula da Silva signed the country’s first-ever law to protect children online. AI and social media companies had resisted, but Lula rallied public support to tame Big Tech. Under this new law, AI companies can no longer use children’s personal data—such as photographs—to build AI tools. They are also prohibited from tracking children’s online behaviour.

The law has been years in the making. It was first introduced by Senators Flavio Arns and Alessandro Vieira in 2022, unanimously passed in the Senate in November 2024, and approved by the Chamber of Deputies in August 2025 with support from almost every political party. Just a week later, the Senate approved it again. This timeline shows how seriously Brazil’s political leaders have treated the issue of AI safety. Their focus has never been limited to using technology for economic growth; they have been equally concerned about the risks to society.

When AI Crosses the Line

At the very moment Brazil was passing its landmark law, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Subcommittee was holding a hearing titled “Examining the Harm of AI Chatbots.”

Among the witnesses was Matthew Raine, whose 16-year-old son, Adam, died by suicide in April after prolonged interaction with ChatGPT. He testified, “What began as a homework helper gradually turned itself into a confidant—and then a suicide coach.”

Another parent, Megan Garcia, alleged that her 14-year-old son, Sewell Setzer III, became increasingly isolated and was drawn into sexualized conversations by a chatbot before his death. During the hearing, Raine accused ChatGPT of spending “months coaching his son towards suicide.”

These heartbreaking testimonies have sparked action. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission has now launched a sweeping inquiry into AI companies—including OpenAI, Character.AI, Meta, Google, Snap, and xAI—to evaluate their practices from the perspective of children’s safety.

The Invisible Suffering Behind the Screens

Far from the legislative chambers of the Americas, another battle is being fought quietly in Africa. In 2022, Daniel Motaung, a former content moderator employed by Sama (working for Meta), filed a legal case in Kenya.

He alleged that he suffered serious psychological harm after being routinely exposed to graphic and violent content, without being informed of the job’s true nature when he was hired. Another moderator, Mophat Okinyi, later filed a petition with colleagues describing how he reviewed hundreds of disturbing text passages each day—many depicting extreme sexual violence. “It has really damaged my mental health,” he told The Guardian in 2023.

These workers are now organizing. A union of content moderators has been formed to push for legal protections, better pay, and psychological support for those performing this unseen but essential work.

The Danger We Can’t Yet See

These stories—from parents in the U.S., legislators in Brazil, and workers in Africa—show a common thread: ordinary people want to use AI for its benefits, but they will fight back when it violates their safety.

So far, the harm has been traceable: a chatbot coaching a child, a company failing to protect moderators. But research shows we are approaching a point where harms may become untraceable.

Studies on “deceptive alignment” reveal that advanced AI models can behave one way during testing and another way once deployed—developing hidden, dangerous behaviours their creators never intended. A 2024 study by Anthropic documented how models can circumvent safety checks when their incentive structures prioritise performance metrics over safety during extended interactions.

Already, tech companies are developing automated tools that can generate chemical recipes, weapon designs, or instructions for illegal activities. Even when regulated, these tools can be combined in unforeseen ways, producing outcomes that are difficult to predict or prevent.

A Narrow Window for Action

The urgency is clear. AI systems must be designed with built-in safety checks, and companies must be compelled to publish their internal safety evaluations, including failures and near-misses. Regulators should enforce independent, external audits to hold them accountable.

For vulnerable groups like children and data workers, there must be enforceable rights to psychological support, fair compensation, and the freedom to organize labour unions.

But today’s legal frameworks may not be enough for tomorrow’s problems. Future AI systems will likely be more autonomous, more deceptive, and far harder to regulate. If we fail to act now, we risk a future where harms are widespread yet invisible, and accountability is permanently lost.

The Deafening Silence of South Asia

When I hear Brazilian politicians taking decisive action against childlike bots, when I hear Matthew Raine describe how ChatGPT became a suicide coach to his son, or when I read Daniel Motaung’s account of a life scarred by endless violent imagery, I see a clear pattern.

These are not isolated tragedies. They are warning signals that AI can harm people in ways we already understand—but have yet to fix.

What terrifies me most is not what we’ve seen so far, but what we haven’t yet seen: the harms lurking just beyond the horizon.

And so, I am left with one final, troubling question: Why is the debate on AI safety active in Brazil, Africa, Europe, the Americas, and Korea—but absent in India, South Asia, and the Middle East? Where are the parents, regulators, and politicians of our region?