[By thetaxhaven, under Creative Commons]

Each time I hear the word bitcoin, I begin to feel a niggling something go down my spine. It is entirely possible that by the time I am done with articulating what I have to, believers in bitcoin may suggest I have no spine. Be that as it may, I feel compelled to opine on the bitcoin mania for a few reasons.

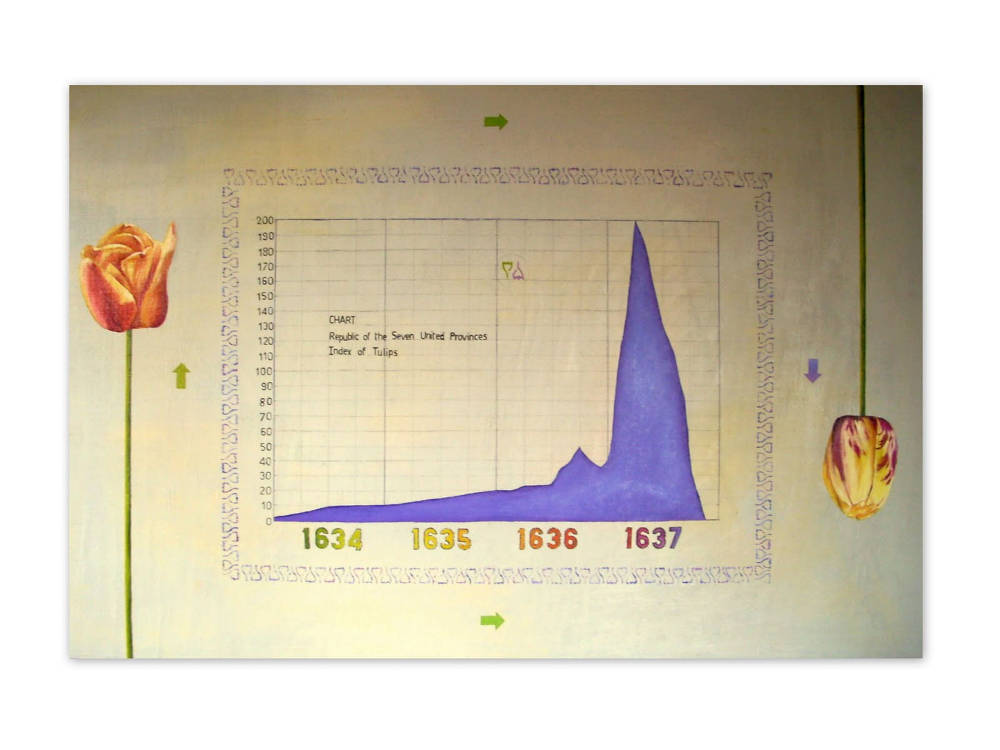

1. Over the last 10-odd days, I have listened in on conversations where multiple opinions have been exchanged on whether or not bitcoins ought to be part of an investment portfolio. As things are, it is a hotly debated subject, is apparently a coveted asset, the least understood, and from the looks of it, has all the makings of a bubble—eerily reminiscent of the tulip mania in 1637.

Why are bitcoins coveted as much, is easy to see. Over the last year, the cryptocurrency has moved only upwards—from $750 around this time last year, it is now closing in on $8,000. The chart reproduced below shows some wild fluctuations as well in preceding months when it fell from over $6,000 to the $5,000 region. The overall momentum though has been upward. A few people have asked me whether I would place my money on this. I have declined to comment.

2. Then there are amusing asides. The Supreme Court of India admitted a plea to regulate the flow of bitcoins into India. Not just that, it has also sought a response from the Central government. While I haven’t been through the submissions articulated in the plea, I am willing to put my neck on the line and submit the plea understands nothing about peer-to-peer (P2P) technology. I also suspect it may have been drafted in a way to mislead the court to believe its intervention is necessary. That the court cannot practically intervene is one thing. I’ll come to that later. For now, I wish the Supreme Court had dismissed the plea as a frivolous one and fined the creature who filed it for wasting its time.

Bitcoin is built on the back of a philosophically beautiful construct. This is where the problem and the paradox lie

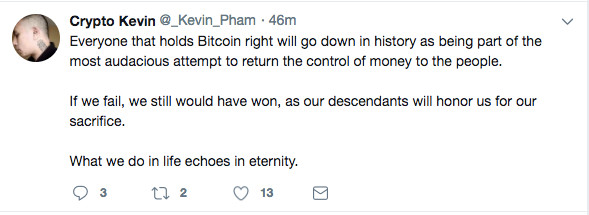

3. But as ideas go, I think bitcoin is built on the back of a philosophically beautiful construct. This is where the problem and the paradox inherent to it lie as well. The current spike in bitcoin prices are being driven by those who believe in it as a political statement—an ideology if you will. Their fight will continue even if they lose money. Gains from it are the last thing on their mind. I’ll come to that in a little while on the back of my notes from an encounter with the legendary Richard Stallman in an earlier avatar of mine.

All this said, I think I must attempt to deconstruct each of my assertions here.

A history of contemporary money

This is a theme that interests me deeply for various reasons. I have delved on the history of money and why it matters in the current debate around identity and privacy. This was a few months ago when the validity of Project Aadhaar was challenged in the Supreme Court.

As for the frenzy around bitcoin, there is much noise and it is time again to go back to basics and ask what is money really. Money is what you are willing to offer for something you may want. In the past, people used to barter goods for services offered. As societies grew larger, a compelling need for formal money in the form of promissory notes evolved. When demand for these notes increased, to keep track of who owes whom how much, banks emerged.

What are banks? Very bluntly put, nothing but dolled-up entities that can maintain a large number of ledger books of debit and credit entries.

To regulate how banks in any country behave, a central bank (like the Reserve Bank of India) are accepted norms. These are powerful bodies because they are mandated by the government and trusted by people to issue promissory notes—pieces of paper underwritten by the sovereign government. A holder of this note can use it to buy something as opposed to bartering in the past. It makes life easier.

The limitation with money of this kind is that it can be used only within a certain geography. Outside those boundaries, another sovereign has its own muscle and issues its own currency. But currencies can be traded. Their intrinsic values may differ though and depend on many economic variables. These variables are what those who dabble in the money market play around with and earn billions of dollars as margins each day in speculating where may the future lie.

As for you and me, the more money we have, the better off we are. So, everybody wants more money. But because the dynamics of the money market are complex, the central bank has a crucial role to play. At any given point in time, it must ensure only a limited amount of money circulates within the system. And people have to compete legally to earn it. Anybody who tries to game the system must be penalised.

This also places a huge moral and fiscal obligation on the central bank. To keep the trust of people going, the authorities led by its chief—in India, the governor of the RBI—must weigh in on complex economic issues to ensure the promissory note it issues contains an intrinsic value. If the bank prints too many of it, people won’t value it and a country’s economy can collapse. How profligate central banks can drive an economy to collapse is the reason why Zimbabwe has now gone to the dogs.

While the happenings in Zimbabwe haven’t impacted the global ecosystem, most people are familiar with what can happen if the system is gamed as it was over the last decade. It eventually led to the collapse of the global financial order in 2008. Remember the excesses committed on Wall Street, the financial capital of the world? How it was done was meticulously documented by Michael Lewis in Liar’s Poker and The Big Short.

Between the book and the film, Lewis, a former bond trader on Wall Street recounts in much detail how on September 15, 2008 Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy and the global financial ecosystem collapsed. It was not because crucial people were in the dark. But because everybody who ought to have kept watch were hand-in-glove. This includes even rating agencies like the much-hyped Moody’s and S&P Global that were fined $864 million and $1.38 billion, respectively, for complicity.

Their looking the other way cost hundreds of millions of people across the world their homes, jobs, savings, and lives. In a sane world where some semblance of morality exists, the billions of dollars a few thousands of people earned to snort cocaine and peddle illicit sex while they destroyed others’ lives would have earned them death by the noose or a bullet through the head.

There is something strange about the nature of immorality. Humans are attracted to it

But they were let off after paying some chump change in fine, are back in business, being wooed again and earning more money. People continue to look in awe at those from Wall Street, fancy financial institutions, rating agencies and Ivy league colleges—when actually they ought to be looked down on with disdain. But there is something strange about the nature of immorality. Humans are attracted to it.

What do we trust then?

This raises a question. Can overpaid book keepers like banks and sovereign entities like governments be trusted with hard-earned money? All evidence has it we ought to be angry. But we aren’t. There were some who were and could see through the fog. They have always maintained the system is a fallible one and there was evidence on their side.

The collapse on Wall Street being just one case in point. Closer home, the rupee was demonetised. It was the kind of Black Swan event that in any other part of the world would have eroded people’s trust in a central bank. That people continue to trust it is a tribute to the power of storytelling.

To insure people against fallible entities, pliable institutions as seen on Wall Street and fantastic storytellers in other parts of the world, a new ecosystem is needed. To do that, Satoshi Nakamoto, an unknown entity (or perhaps a person) who deeply understands technology and the intricacies of the money markets had started work a long while ago to create a parallel universe. They were asking some questions.

- What if there exists a ledger where no bank is needed to maintain it?

- What if there is no government needed to underwrite a promissory note?

- What if there exists a system of notes digitally issued from one person to another person minus any intermediary and authenticated at once by multiple third-party entities?

That it cuts costs and intermediation is one thing—but it is the ultimate political statement any libertarian can make

If it could be accomplished, the global financial ecosystem could be dismantled and all intermediaries, including the government as we understand it now can be done away with. That it cuts costs and intermediation is one thing—but it is the ultimate political statement any libertarian can make.

- At a more micro level, to ensure the authenticity of these notes, what if the ledger books were to be open? That means, at any given point in time, if I make a payment, that note will be visible to many people who can vouch whether it is an authentic note or not in the bitcoin ecosystem.

- Between strong privacy and the evolving nature of encryption, it will ensure nobody can see who makes the payment, who receives it, or attempt to change the value of the promissory note.

- It doesn’t matter where in the world you live in; it can travel digitally. To that extent, it is a global currency. This facilitates free movement of trade and capital—again a libertarian ideal.

- Add to this the fact that this promissory note (or currency) will not exist on a single repository, but across multiple computers on a network spread across the world. If you are connected to the internet, you can access this network. So, it cannot be regulated by any government. This is P2P technology 101. That is why I had stated upfront that whoever thinks the Supreme Court ought to entertain a plea asking it to examine the flow of bitcoin into India is wasting the court’s time. It is a theme for the legislature to debate on and try to figure what kind of framework it must arrive at.

If more perspective may be needed, technology enthusiasts are familiar with the idea of downloading movies and music from BitTorrent sites. Governments have tried to clamp down on the more popular ones. But it continues to thrive.

In much the same way, trying to clamp down on a distributed network that is spread across the world is futile. China’s attempt to ban bitcoin is a case in point. It only appeases the hardliners because the idea of losing control is terrifying. But Chinese smart money knows how to rear its head from the unlikeliest of places—like Estonia for instance. And there is no stopping over the counter (OTC) trading or critical technologies like blockchain that have emerged out of the race to build more robust bitcoins.

- And finally, much like we understand that the amount of money in a system must be controlled, Satoshi Nakamoto has created bitcoin as a finite resource. There are only 21 million bitcoins in circulation. You can choose to give away a part of a single bitcoin as opposed to an entire one. So, the universe is expandable, but in a finite way. To that extent, it is a carefully thought through ecosystem as well.

This is not to suggest it is a perfect ecosystem. Frailties exist. But that is in the nature of all technologies until it reaches a “tipping point”. On the face of it, bitcoin seems to be on the verge of a tipping point. More people were beginning to accept it as a mode of payment. If it gains significant traction, the ramifications can be enormous.

That is why, not just in China, but regulatory authorities in markets from the US on one side of the world to Australia on the other side think it terrifying. It holds the potential to pull the rug from beneath their feet.

As for all arguments against bitcoin—that it is a vehicle primarily used to procure drugs and pornography—I refuse to buy it. Because it is now well-established that innovations are first embraced by those in the pornography business. They are the earliest adopters of technology and it stands proven for at least two decades.

Bitcoin as an ideology

This is where the paradox begins and the questions come in fast and furious. How do you measure the intrinsic value of a bitcoin?

That is a very interesting question. To measure the value of something, it ought to be backed by something precious. At least that is how our minds comprehend value. The money that we cherish is valued because as articulated above, it is guaranteed by the sovereign. Take that promise out and what is it, but a myth? This is where the irony that underlies bitcoins begins to it manifest itself. And most of us still haven’t wrapped our heads around it. The much-acclaimed analyst Ben Thompson who writes on the intersection of business and technology puts this into perspective on Stratechery way back in 2014.

“The defining characteristic of anything digital is its zero-marginal cost…Bitcoin and the breakthrough it represents, broadly speaking, changes all that. For the first time, something can be both digital and unique, without any real-world representation. The particulars of bitcoin and its hotly-debated value as a currency I think cloud this fact for many observers; the breakthrough I’m talking about in fact has nothing to do with currency, and could in theory be applied to all kinds of objects that can’t be duplicated, from stock certificates to property deeds to wills and more.”

When looked at from this perspective, there is no intrinsic value to a bitcoin. What we have on hand now and what we work off is a system of currency that is built on fraud and narratives. As recently as 2008, it had brought the global financial system to its knees. And the alternative staring at us is something called bitcoin, an alternative narrative and a philosophy built on the back of technology and Utopian ideals. Not just that, it stands at a tipping point. How do we measure this?

It is tough. If you may need perspective, cast your eye over this screenshot of a tweet that I took on Sunday morning on November 19, 2017.

To make some sense of it all, I have to go back to my days as a technology reporter. Richard Stallman was visiting India and I had a chance to interact with him at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in Mumbai. He was evangelising the Free Software Foundation, his battle against “copyrights” and vocalising his concerns around what he thought reprehensible ideas, like software patents and digital rights. He wanted this principle extended across multiple domains. He called this idea “copyleft”.

I was asked to tail him so that I could report on all of what I could see. While at it, I admit to being smitten by the man and his passion for all that he brought to the table. For a young sod like me, it was easy to be enamoured by Stallman and his idealism. It took some while though to figure out that while Stallman had all of the right ideas, I couldn’t live my life basis his principles. He was happy to stay single and frugal. I wasn’t. I now know he thinks in black or white. There are no shades of grey. I wasn’t ready for that either.

Some thinking and much talking to people later, I figured there were many like me who like Stallman, but either do not have the mental muscle to emulate him or choose not to. In my head, I parted ways with his philosophies. There is only so much idealism I can take. At some point, pragmatism kicks in. I have a mouth to sustain and mouths to feed.

In speaking to my friends embedded in technology, I could see the hard-core ones there too were as conflicted as I was. They appreciated him for staying true to his word. But couldn’t see their lives play out the way Stallman would want it to. It was time for everyone to part ways from the idealism of Stallman to the pragmatism of Linus Torvalds without forgetting the best of what Stallman offered. We now know most of the world’s computing backend is powered by Linux.

As a person, Stallman was a pleasant and gentle creature to be around. He had a quirky sense of humour that I thought endearing. But how was I to know he hated the word “Linux”? Because when used in isolation, he thought of it a bastardisation of his philosophy. I thought I almost got my skin pulled out when I asked him about the future of the operating system. It was a faux pas on my part. Because in his world, he insisted everybody refer to it as “GNU/ Linux”.

Be that as it may, there is no taking away from his multiple contributions. The world and the computing prowess we now take for granted would not have been possible without his idealism.

Then on the other hand, Linux wouldn’t have taken off as it has if it were only a political statement. It needed to show its prowess as a pragmatic alternative to the monoliths in the business. It did and much of it was possible because of evangelists like Stallman.

This is not just a battle about technology. This is about world views

That brings me back to bitcoin. If I were to draw a parallel, it seems to me that the “Satoshi Nakamoto” school of thought that wants to make a clean break from the current financial ecosystem and build a new world order thinks of it as a political statement. This is not just a battle about technology. This is about world views. And much like the fissures in Stallman’s world were evident, I think I see some in the bitcoin camp. The debate among bitcoin miners on bitcoin cash versus bitcoin gold and the confusion in the ranks, for instance, are pointers in that direction.

Bitcoin as an investment

In hindsight, if Stallman had his way, we’d have lived in a perfect world. The revolution he ignited would have been the perfect one. I liked the sound of it too—much like I love the sound of bitcoins displacing the current financial dispensation. But it sounds unlikely.

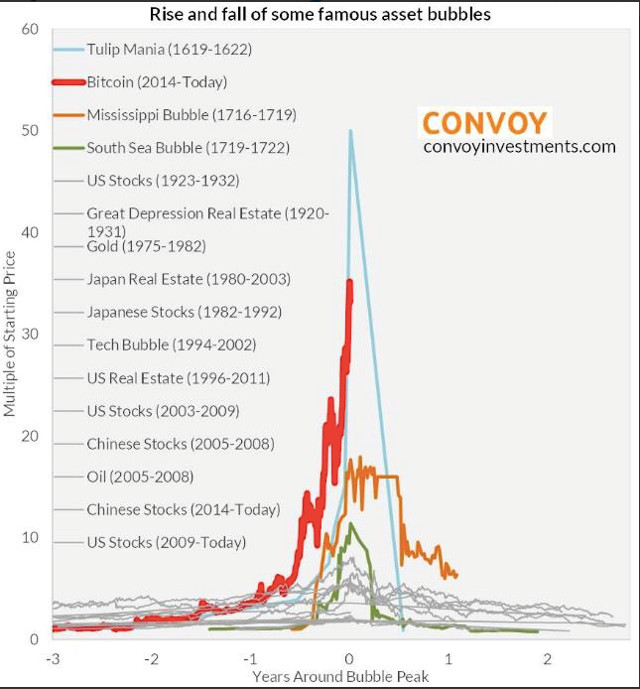

I feel compelled to state that because historical evidence on bubbles of all kinds—including the most famous of them all, the tulip mania—points to just that.

It is only pertinent then you ask why should the excitement around bitcoin be a bubble? For that matter, what is to suggest that there is a bubble? An interesting report by Paul Donovan, the chief economist at UBS Securities attempts to answer that question.

“A bubble generally has to involve some kind of novelty. It can be the underlying asset that is new. Dutch tulips were new and exotic. Eighteenth century canals were new, on the scale that they were being built. Nineteenth century railways were new. Twentieth century cars and radios were new. Turn of the century internet stocks were new.

Cryptocurrencies today are new. Alternatively, it can be the financial innovation that is the novelty. Cash-settled futures contracts on Dutch tulip bulbs were new. Large scale joint stock companies in France and England in the early eighteen-century were new. Large scale leveraged buyouts in the 1980s were new.

Novelty matters to a bubble, because it makes valuing future fundamentals more difficult. Novelty allows the dread phrase "this time it is different" to be spoken. If fundamental value is to be ignored, there has to be a reason investors forget the rational lessons of history. Novelty helps.

A bubble must promise real world returns at some distant date. If real world returns are expected quickly, the failure to realize those returns quickly will be obvious quickly. It took time for tulip bulbs to become tulips. The Mississippi and South Sea bubbles of the early eighteenth century promised non-existent riches from trade. The non-existent riches were supposed to be earned in the future. The internet bubble promised that we would all be buying pet food online – not immediately, but in the new millennium. The gap between selling financial assets and achieving the real world returns lets irrationality build. The asset price continues to rise because "this time it is different" and bubble buyers believe that returns will come pouring in if only they wait long enough.

The final characteristic of a bubble is that a bubble bursts. The sudden drop in the asset price is the defining characteristic of a bubble. It is the bursting of a bubble that is of most interest to the economist. This conclusive signal comes too late for the bubble buyer, of course. The bubble buyer must suffer the result.”

When looked at from this perspective and now asked, “why are bitcoin prices as high as it?” my understanding is, a lot of it has to do with the recent Chinese clampdown on bitcoin. The immediate aftermath was a slump. But the flight of capital out of China was temporary. Everybody is feverishly bidding for all the action they missed out on. Meanwhile there are punters gaming the system as well as they would in any other market when they spot an opportunity. Between all of these, the prices have moved up. It is only a matter of time before prices come down.

Does bitcoin as a currency have the muscle to withstand multiple onslaughts from various stakeholders in the ecosystem?

The larger question on the mind and one I am deeply conflicted about is whether bitcoin as a currency has the muscle to withstand multiple onslaughts from various stakeholders in the ecosystem—whether it be governments, private players, regulatory authorities, or those looking to make a fast buck. Incidentally, this is the subject of much debate between the writer on the theme and readers on the Wall Street Journal and perspectives of all kinds can be heard.

Ideological battles in a marketplace can last so long as the money to back it lasts

What I do know is that basis what I have seen in the past, ideological battles in a marketplace can last so long as the money to back it lasts. After that, it morphs into something else altogether. In the interim though, much good comes out as well. In the race to find the ideal cryptocurrency, blockchain as a technology is one outcome, and the experiments at TCS around it and how entities like Bajaj Electricals are deploying it to pay for material in real time are real time cases. Who knows what else may emerge?

On whether to invest in bitcoin, personally, I’d stay out of what looks like a bubble. But I’m willing to get into an all-night slugfest over an ideology so long as we keep money out of it. To that extent, I’d go with pragmatism as opposed to idealism. And yes, I know that sounds terrible.

(This is a modified and expanded version of a column that was originally published in Livemint)

Correction: Moody’s was fined $864 million, and not $864 billion as stated in an earlier version.