[Photo by Ruthson Zimmerman on Unsplash]

Good morning,

In spite of having access to data, why do professional forecasters often fail at predicting outcomes? Nate Silver attempts to explain this in The Signal and the Noise: The Art and Science of Prediction.

“In statistics, the name given to the act of mistaking noise for a signal is overfitting.

“Suppose that you’re some sort of petty criminal and I’m your boss. I deputize you to figure out a good method for picking combination locks of the sort you might find in a middle school—maybe we want to steal everybody’s lunch money. I want an approach that will give us a high probability of picking a lock anywhere and anytime. I give you three locks to practice on—a red one, a black one, and a blue one.

“After experimenting with the locks for a few days, you come back and tell me that you’ve discovered a foolproof solution. If the lock is red, you say, the combination is 27-12-31. If it’s black, use the numbers 44-14-19. And if it’s blue, it’s 10-3-32.

“I’d tell you that you’ve completely failed in your mission. You’ve clearly figured out how to open these three particular locks. But you haven’t done anything to advance our theory of lock-picking—to give us some hope of picking them when we don’t know the combination in advance. I’d have been interested in knowing, say, whether there was a good type of paper clip for picking these locks, or some sort of mechanical flaw we can exploit. Or failing that, if there’s some trick to detect the combination: maybe certain types of numbers are used more often than others? You’ve given me an overly specific solution to a general problem. This is overfitting, and it leads to worse predictions.

“The name overfitting comes from the way that statistical models are ‘fit’ to match past observations. The fit can be too loose—this is called underfitting—in which case you will not be capturing as much of the signal as you could. Or it can be too tight—an overfit model—which means that you’re fitting the noise in the data rather than discovering its underlying structure. The latter error is much more common in practice…

“Overfitting represents a double whammy: it makes our model look better on paper but perform worse in the real world. Because of the latter trait, an overfit model eventually will get its comeuppance if and when it is used to make real predictions.”

Then there’s underfitting as well. We’ll talk about that some other time.

In this issue,

- A new Ikea

- Zoom dysmorphia

- Agile is better

A new Ikea

As the pandemic extracts its toll, we are listening in to thought leaders and reading up on how businesses are adapting. That is why when Harvard Business Review decided to get under the skin of how the brick-and-mortar retail giant Ikea is at work to alter its DNA, it got our attention. HBR engaged in a conversation with Barbara Martin Copolla, Ikea’s chief digital officer (CDO), who has worked at places such as Google, Samsung and Texas Instruments in earlier avatars.

“In practical terms, we’ve approximately tripled ecommerce levels in three years. We have transformed our stores to also act as fulfilment centers. To make that work, the flow of goods needed to change, the supply mechanisms needed to change, and also the floorplans of the store needed to change. Ecommerce is open 24 hours a day, while traditional stores are not, which means we’ve needed to learn how to operate at two speeds, while operating from one space. Goods can be delivered from the stores, or from different distribution centers—and algorithms are helping figure out where the goods are being sourced from. We’re rapidly expanding data and analytics and changing how they’re embedded in decision making.

“With the pandemic and with the closure of approximately 75% of our stores, we ramped-up and accelerated even more as people turned online and towards digital solutions. Things that would normally take years or months were carried out within days and weeks.

“The digital transformation is not a goal in and of itself, and it is so much more than technology. We are transforming our business: We are exploring potential new offers to customers, new ways to bring our offers to customers, and new ways to operate our business. And in order to be successful, digital needs to be embedded in every aspect of Ikea. Digital is a way of working, making decisions, and managing the company.”

There is much else Copolla has to say and it is compelling.

Dig deeper

You might not have heard this word, but you might have felt it

A piece in Wired explores a post-pandemic phenomenon related to staring at a Zoom screen, sometimes at our own faces projected on the monitor, and worrying that it just doesn’t look right. There’s a name for it: Zoom dysmorphia.

Amit Katwala writes: “In the age of Zoom, people became inordinately preoccupied with sagging skin around their neck and jowls; with the size and shape of their nose; with the pallor of their skin. They wanted cosmetic interventions, ranging from Botox and fillers to face-lifts and nose jobs. Kourosh and colleagues surveyed doctors and surgeons, examining the question of whether video-conferencing during the pandemic was a potential contributor to body dysmorphic disorder. They called it ‘Zoom dysmorphia’.

“Now, with the rise in vaccinations seemingly pushing the pandemic into retreat, new research from Kourosh’s group at Harvard has revealed that Zoom dysmorphia isn’t going away. A survey of more than 7,000 people suggests the mental scars of the coronavirus will stay with us for some time.”

The key is to know that one, cameras distort our faces, and two, we are not alone.

Katwala writes, “front-facing cameras distort your image, like a ‘funhouse mirror,’ she says—they make noses look bigger and eyes look smaller. This effect is exacerbated by proximity to the lens, which is generally nearer to you than a person would ever stand in a real life conversation…

“[T]he best way to fight Zoom dysmorphia is through awareness, Kourosh argues… ‘A lot of people are suffering from the negative mental health impacts quietly,’ Kourosh says. It is, she says, about ‘helping people know they’re not alone.’ ”

Dig deeper

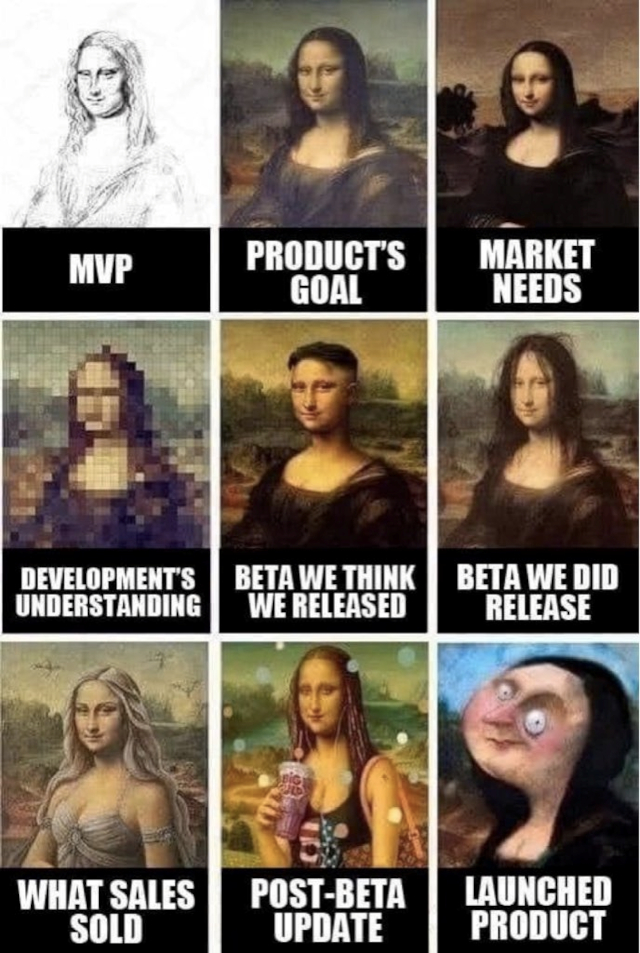

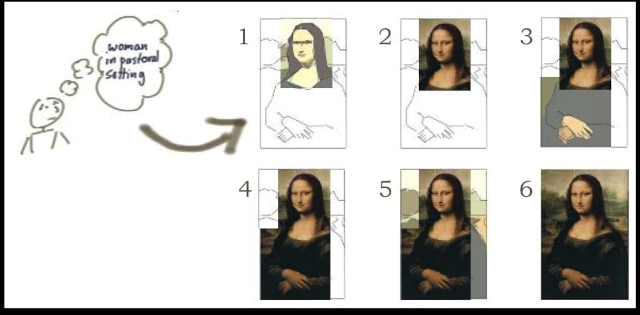

Agile is better

Traditional launch

Agile launch

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)