[Photo by Marc-Olivier Jodoin on Unsplash]

Good morning,

The first principle, Richard Feynman famously said, “is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.”

In The Ten Commandments for Business Failure, Don Keough highlights three cases where business executives fooled themselves.

He writes: “Enron fooled many people, including many in the firm itself. Yet Enron people were bamboozled simply because they did not really think about what they were looking at in the balance sheets. They were so eager for the implausible and incomprehensible numbers to be true that they ignored them. The business press was equally gullible. They wanted the ‘hot’ story, not necessarily the truth. Again and again, art forgers and con artists of all stripes exploit the gullibility of even the most sophisticated among us. They understand our need to at times believe fantasy over reality.

“In the late 1940s, when Pepsi was selling ‘twice as much for a nickel,’ Coca-Cola executives fooled themselves by quarterly reporting sales of the product in cases. And those case sales reports showed that Coke was selling far more cases than the competitor. The only problem was that a case of Coca-Cola was twenty-four six-and-a-half-ounce bottles while the case of Pepsi was twenty-four twelve-ounce bottles. No one asked the obvious question, ‘If we are selling more cases, why are they constantly gaining on us?’ The reality of that question led to the final breakthrough of larger-size bottles for Coca-Cola.

“Detroit automakers fooled themselves for years looking at the sales figures they wanted to look at rather than thinking about the total picture of the global automotive industry. They even fooled themselves on their standards of quality. They set their own internal standards, assigned their own value to a measure of quality, and then patted themselves on the back when they came close to their own standards. The Japanese had no standards. They said, ‘Let’s build the best car we can. And let’s keep improving that car.’ Obvious. And brilliant.

“The reason why people so often fool themselves is the tendency to see what we want to see, rather than see the reality. We all fall into what’s called the confirmation trap at one time or the other. The solution is to question ourselves, and seek honest feedback from others.”

In this issue

- Going vegan

- How not to teach math

- Skewed data

The ethics of food

Mukund Padmanabhan’s essay in The Indian Express yesterday on why he chose to embrace a vegan diet had our attention. This was because when read between the lines, it wasn’t just about making a personal choice. But making an informed decision when confronted with ethical dilemmas a society faces and choosing what is in the greater common interest.

“For the last year-and-a-half, I have gone from being an occasional non-vegetarian to a vegan. Almost vegan is much more accurate, as I have allowed myself to, on occasion, eat something with butter or ghee rather than risk offending a host and, much worse, cadged a bite or two of some milk-infused burfis. Moreover, as the former US President Jimmy Carter admitted in a different context, I have looked at non-vegetarian dishes nostalgically and lovingly, or been routinely disloyal in my mind.

“What surprises me though, as a struggling and imperfect vegan, is how people react to veganism. Some believe it is a form of food puritanism, which it most definitely is not. Others dismiss it as a result of some passing woke trend, an attempt to be a food fashionista… Although there are some activists who have given veganism a bad name, very few appreciate that it could also be arrived at through deliberative philosophical inquiry into the ethics of food, its production and consumption. My so-called ‘conversion’ occurred while reading and re-reading Peter Singer, the brilliant (and controversial) Australian philosopher now based at Princeton, as preparation for a couple of bioethics lectures to university students…

“When it comes to thinking about how our food is produced, we would rather not know, or deal with our cognitive dissonances by suppressing what we do know. Allowing oneself to think critically and candidly about food may demand making challenging dietary changes.”

Dig deeper

How not to teach math

Once in a while we use the newsletter to highlight exceptional Twitter threads we come across, and recently we came across one by Samit Dasgupta, a mathematician at Duke University, famous for answering a 100-year-old question in mathematics.

Like many parents, he recently had a chance to observe a test his daughter and her classmates had to take—solving as many problems as they could in a minute. For many who have taken various entrance exams, which in turn opened up career opportunities, it might seem like a very useful exercise. Something that would help the kids in the long run.

But, that’s not how Dasgupta looked at it. He tweeted: “My daughter was frustrated by an activity in a math class where they had to solve as many problems as they could in a minute. I told her this bears no connection to actual mathematics—I’d been working on the problem I just solved for 20 years, which blew her mind!”

What’s interesting is not the original tweet itself, but the many questions that came up and the way he answered them. They are thought provoking, and should lead to serious discussions. Here are two samples.

Numericalguy: There is nothing wrong with having to solve as many problems in a minute as long that is not the only way they are asked to learn. If we can open to “quick on our feet”, why not to this. I do not see any harm.

Samit Dasgupta: I saw—quite literally—lots of harm. I happened to be observing the class that day. Not just my daughter, but all of the students were quite stressed. While the class up to that point had a nice atmosphere and total student engagement, the students basically flipped after that point. There was audible discomfort and panic during the minute. Multiple students became upset they could solve only one or two problems in the time. The atmosphere of the whole class changed after that point, and the students were counting the minutes to leave. I don’t think it’s pedagogically useful, and moreover it introduces unnecessary disparate effects on various groups. I literally see no benefit and lots of negative impacts.

Victor Stewart: “It’s still an incredibly accurate way of ranking mathematical ability amongst students: though a delta of 10 might be noise, one of 100s surely is not.”

Samit Dasgupta: So much to unpack here. (1) The point is to teach mathematics, not to “rank mathematical ability.” (2) The idea that there is a linear ordering of mathematical ability that we can test for is inherently flawed. (3) Even if you do want to test for some meaningful measure of mathematical ability, this is an incredibly inaccurate way of doing so. In particular: (4) there is good reason to believe that such tests have disparate effects on various groups, which is an unnecessary effect to introduce when it is essentially unrelated to the teaching goal.

Dig deeper

- Mathematicians find long-sought building blocks for special polynomials

- Twitter Q&A with Samit Dasgupta

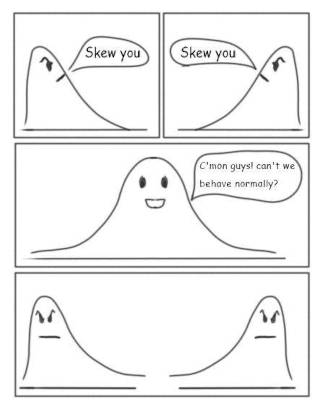

Skewed data

(Via DataScience Dojo on LinkedIn)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)