[Many South Indians think Kanchipuram when they think wedding. Photo by Avinash Uppuluri on Unsplash]

Welcome to the fifth edition of The Growth Factor Weekly (TGF Weekly). The newsletter explores some of the biggest questions around small businesses through the stories of MSME owners, bankers, investors, customers, employees and technologists. It will reach your inbox every Friday at 5:00 PM IST. (Sign up now.)

In this issue:

- Why Kanchipuram should weave stories

- What MSMEs can learn from the school of fish

- Can MSMEs account for 60% of exports in two years?

Happy reading!

The big debate | Why Kanchipuram should weave stories

It’s hard to see how Kanchipuram, a temple town located about 70 km from Chennai, became a hub for silk saris. It has no natural advantages, unlike some of the other clusters such as Sivakasi or Coimbatore. Sivakasi’s dry weather was ideal for making matches and fireworks. Coimbatore’s rich black soil enabled cotton cultivation, and out of it, grew its textile industry. But Kanchipuram gets its two most important ingredients, silk and zari, from Karnataka and Surat.

Kanchipuram’s strength comes from its know-how and brand. However, even before the pandemic and lockdown, businesses there complained that things were not as good as it used to be. Weavers and most retailers were making too little money. Youngsters were voting with their feet, to seek employment in automobile and electronic manufacturing plants coming up nearby.

When I visited the town some years ago, almost everyone I met had a strong view on whether they should simply let automation and mechanization take over. That would reduce costs, increase production, and maybe take the brand to more customers. “Technology is already here. We use computer-aided design,” one of them said.

[A silk sari retailer in Chennai. Photo by Ravichandar84 via Wikimedia Commons]

Others were sentimental. It’s not the product, but the whole process. Even if a machine can replicate, it’s not the same thing. I recently came across two papers that highlighted how both are interconnected.

In Alien Weave: crafts versus consumerism, Vijaya Ramaswamy shares a perspective from her conversation with Nalli Kuppusami, who runs a popular silk sari chain. Ramaswamy writes,

“Nalli Kuppusami... told me that his grandfather had a clientele which was interested in the possession of a sari which would be exclusively for themselves. He points out that the maximum length that could be woven on a traditional handloom was 18 yards. Therefore no more than three women could wear the same type of saree throughout the world. Powerlooms and CAD have led to the virtual disappearance of this quality of exclusiveness.”

Now, what about mass-customization?

In an essay, Kanchipuram Sari: Design for Auspiciousness, Aarti Kawlra shows how the design and technique, the process, and the product all come together to define its brand.

A sari can weigh one to two kilograms—which rules out daily use. They are bought and used for special occasions—such as marriages. And the weavers strictly adhere to various prescriptions when they weave these special saris.

[Kanchipuram silk saris play an important role in the culture of Tamil Nadu. Carnatic singer MS Subbulakshmi was a big fan of ‘Kanchivarams’ as the saris are popularly known. This image is a screenshot from a Youtube video]

Here’s an interesting paragraph from the essay:

“Once taken off the loom, the sari is susceptible to pollution unless it is sold within a certain acceptable time period. The sellers of ‘new’ cloth perceive themselves as selling auspiciousness. Once sold to a potential user, it becomes ‘old’ even if it has not been actually used. It is thought to have lost its auspiciousness. Sari retailers seldom take back saris once sold because they believe that the sari is no longer fit for use. It is the responsibility of the retailer, whom his customer trusts, not to sell her inauspicious, impure, soiled cloth; which may have been imbued with the unknown and harmful qualities of the body that first donned it. When customers insist on returning or exchanging saris, the latter are kept aside for discount sales in which there is no guarantee of the auspicious status of the cloth.

“In fact, the month of Adi, otherwise an inauspicious month for marriages and other ceremonies, is a month when Radha Silks holds their largest discount sale. Saris bought and sold during this period come with the clear understanding that they are with some flaw, and hence the lowered price.”

What’s the way ahead for Kanchipuram, given the needs and constraints of both weavers and customers? In one scenario, both co-exist. Advanced technologies produce an exact replica of Kanchipuram saris, almost as if they are handwoven—except they could cost less, thanks to scale. At the same time, master weavers continue to produce them in the traditional way—and they will charge a huge premium for it.

What could potentially differentiate the two? One method would be storytelling. Each piece comes with the story of how it’s made. And customers pay not only for the product but also for the story.

The Bottomline: The one who tells the best story wins.

Dept. of innovation | What MSMEs can learn from the school of fish

Writing in Mint, Bindu Ananth and Nachiket Mor suggest creating synthetic supply chains connecting small businesses that would enable them to reduce risks, and hence access funds. Small businesses with big, trustworthy customers usually find it easy to access funds, because the big customer can absorb risk and provide some amount of assurance to lenders.

But what about, say, a standalone hotel in Kota, Rajasthan?

Ananth and Mor write:

“In the fast-moving consumer goods industry, for example, stand-alone MSMEs seeking to supply intermediate goods face risks comparable to those being experienced by that hotel in Kota, but those that are tightly connected to a large company, such as Hindustan Unilever, get a lot of that uncertainty taken away, leaving them free to focus on their core competencies, and in the bargain becoming much better candidates for both debt and equity. Wherever these well-defined supply chains do not exist, the role of synthetic supply chains becomes critical. These can, for example, be provided by companies that connect the MSME to the broader economy and help mitigate payment, demand or supply uncertainties. For example, Oyo or Airbnb can work with our budget hotel in Kota to provide it a minimum level of occupancy through its advanced booking systems and by helping it access a much wider range of travellers than it could on its own.”

Chart of the week | Can MSMEs account for 60% of exports in two years?

By Vasisht Balaji Srinivasan

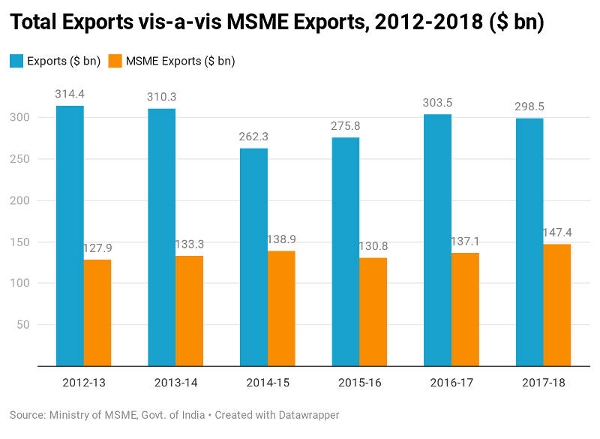

Nitin Gadkari, minister for MSMEs, said the sector will account for 60% of total exports in two years. How realistic is that claim?

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/F19y0/2/

Both exports and MSME exports, in general, have been volatile between 2012-13 and 2017-18, for which numbers are available. Overall exports suffered close to a 16% drop in 2015-16, compared to the previous year, but have now rebounded to 2012-13 levels, at around $314 billion.

Interestingly, the share of MSME exports has increased from 40.68% to 49.38% of total exports in this same period. MSMEs claimed over half the share of export revenue in 2015-16. Now, MSME exports have grown by close to 4.2% year-on-year since 2012-13. If this trend continues, can it touch 60% of total exports by 2023-24?

That would depend on the growth of total exports. Total exports have actually declined by 0.65% over the past five years, and this year it could drop further due to the global pandemic. However, if overseas demand goes up and supply chains are back in place post-COVID, we will see more exports.

Will MSME exports grow faster than that? The government seems to believe that the emphasis that has been placed on MSMEs in the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan will push the growth. However, for it to hit the magic number of 60% in two years, MSME exports will have to touch $180 billion.

Note: This weekly newsletter is curated by Founding Fuel’s senior writer NS Ramnath, who is researching industrial clusters in Tamil Nadu on a Bharat Inclusion Fellowship. Bharat Inclusion Fellowship, an initiative of CIIE.CO of IIM, Ahmedabad, is aimed at addressing the knowledge gaps that prevent entrepreneurs from developing effective solutions for the underserved.

TGF Weekly will share insights from his research and reporting. The newsletter is a part of the conversation we will have with our community—on our website, over video conferences, webinars and a Discourse platform we are setting up. We will keep you posted.

Please do share this newsletter with friends and colleagues who might be interested in this theme. Thanks for being a part of what promises to be an incredible journey of learning and insights. (Sign up now.)