[When wars linger, resolution fades.]

Not since the late 1930s has the global order been subjected to such a dense accumulation of stress tests. From Europe to the Asia-Pacific, conflicts and potential conflicts are no longer moving toward resolution but hardening into open-ended conditions of instability. The war between Russia and Ukraine—now far beyond its initial military phase—and rising tensions across the South and East China seas are not isolated crises. They are manifestations of a deeper structural shift in how power is exercised, contested, and constrained.

What links these disparate theatres is not ideology, but the behaviour of global and regional powers operating under conditions of rising hegemonic instability. Pathways to conflict resolution are eroding, replaced by prolonged ambiguity and provisional arrangements. For firms, markets, policymakers, and strategic planners alike, this is no longer merely a period of elevated risk. It is a phase in which uncertainty itself is in danger of becoming institutionalised. The absence of credible endgames—rather than the presence of active conflict alone—is emerging as the defining feature of the global order.

Across theatres, the pattern is consistent. Coercion is increasingly normalised. Deterrence becomes as much psychological as military, and peace—where it exists—is temporary and conditional. The central danger is not a single dramatic rupture, but a world in which unresolved conflicts steadily narrow strategic choices and raise long-term costs.

[The key actors shaping a world without endgames.]

Europe: Worsening Challenges

In Europe, the Russia–Ukraine war has moved far beyond a contest over territory. It has become a systemic challenge to the post–Cold War security architecture. Despite periodic diplomatic gestures and bursts of rhetorical optimism from Washington, Moscow has shown no inclination to revise its core objectives. Western strategy remains caught between two competing impulses: the desire to contain escalation and the hope that a negotiated pause might stabilise the situation. The result is a conflict suspended between war and peace—neither decisively fought nor credibly settled, and therefore structurally unstable.

For Europe, the war has become a test of whether the continent can preserve a normative security order that does not reward coercion, revisionism, and the use of force to alter borders. A settlement shaped largely by Vladimir Putin presents stark dilemmas for the European Union. Any agreement that implicitly or explicitly legitimises territorial conquest would corrode the EU’s foundations and weaken the principles underpinning its foreign policy credibility. At the same time, a prolonged war continues to drain economic capacity, divert fiscal resources, and erode political cohesion.

Internal asymmetries compound the challenge. Frontline states in Eastern Europe tend to view compromise as existential, while others prioritise economic stability, inflation control, and energy security. This divergence makes consensus fragile precisely when unity is most needed.

China has quietly but persistently learned to exploit these divisions. Through infrastructure investment, trade relationships, and sustained political engagement, Beijing has embedded economic and institutional leverage that can be activated during moments of stress. Any Chinese participation in a peace process would not be neutral. It would seek to weaken transatlantic cohesion, normalise coercive territorial revisionism, and entrench Chinese influence within European political and economic structures.

Europe’s predicament is further compounded by a deeper and more structural constraint: its asymmetric economic dependence on China. This dependence is embedded in supply chains, industrial policy choices, and financial incentives that increasingly shape Europe’s strategic behaviour—often in ways that conflict with its stated geopolitical objectives. The imbalance is visible not only in finished goods, but more critically in inputs. Advanced manufacturing sectors—automotive, renewable energy, pharmaceuticals, electronics, and precision engineering—rely heavily on Chinese intermediate goods, rare earths, processed materials, and industrial components.

This structural reliance constrains European policy choices. Germany’s automotive sector, Southern Europe’s port and logistics hubs, and Central Europe’s manufacturing bases face distinct vulnerabilities. As a result, EU consensus becomes harder to sustain, and strategic clarity is diluted by economic self-preservation. China’s leverage operates with patience rather than overt coercion, exerted through market access, regulatory signalling, and investment flows. Policy choices that Beijing finds unpalatable can invite commercial retaliation, delayed approvals, or informal barriers.

The Ukraine war has intensified these dynamics. As European governments divert fiscal resources toward defence, energy transition, and social stabilisation, Chinese capital has become more attractive, not less. Investments in ports, logistics infrastructure, battery supply chains, telecommunications, and green technologies deepen long-term dependencies even as they provide short-term relief.

This dependence has direct implications for Europe’s role in any Russia–Ukraine settlement. From Beijing’s perspective, a Europe constrained by economic exposure to China is less likely to adopt positions that threaten Chinese interests—whether in relation to Russia, Taiwan, or the Indo-Pacific. Efforts at “de-risking” rather than decoupling remain politically palatable but strategically insufficient. Supply-chain diversification requires time, capital, and a level of political coordination that the EU continues to struggle to mobilise at scale. National industrial interests override collective action, leaving de-risking more rhetorical than transformative.

Ultimately, Europe’s challenge is not merely resisting external pressure, but reconciling its economic structure with its geopolitical ambitions. A Europe deeply dependent on China cannot function as a fully autonomous strategic actor, nor can it reliably anchor a transatlantic response to a Russia–China axis that increasingly operates across multiple theatres. Until this contradiction is addressed, Europe will remain strategically consequential but structurally constrained—present at the table, yet limited in its ability to shape outcomes.

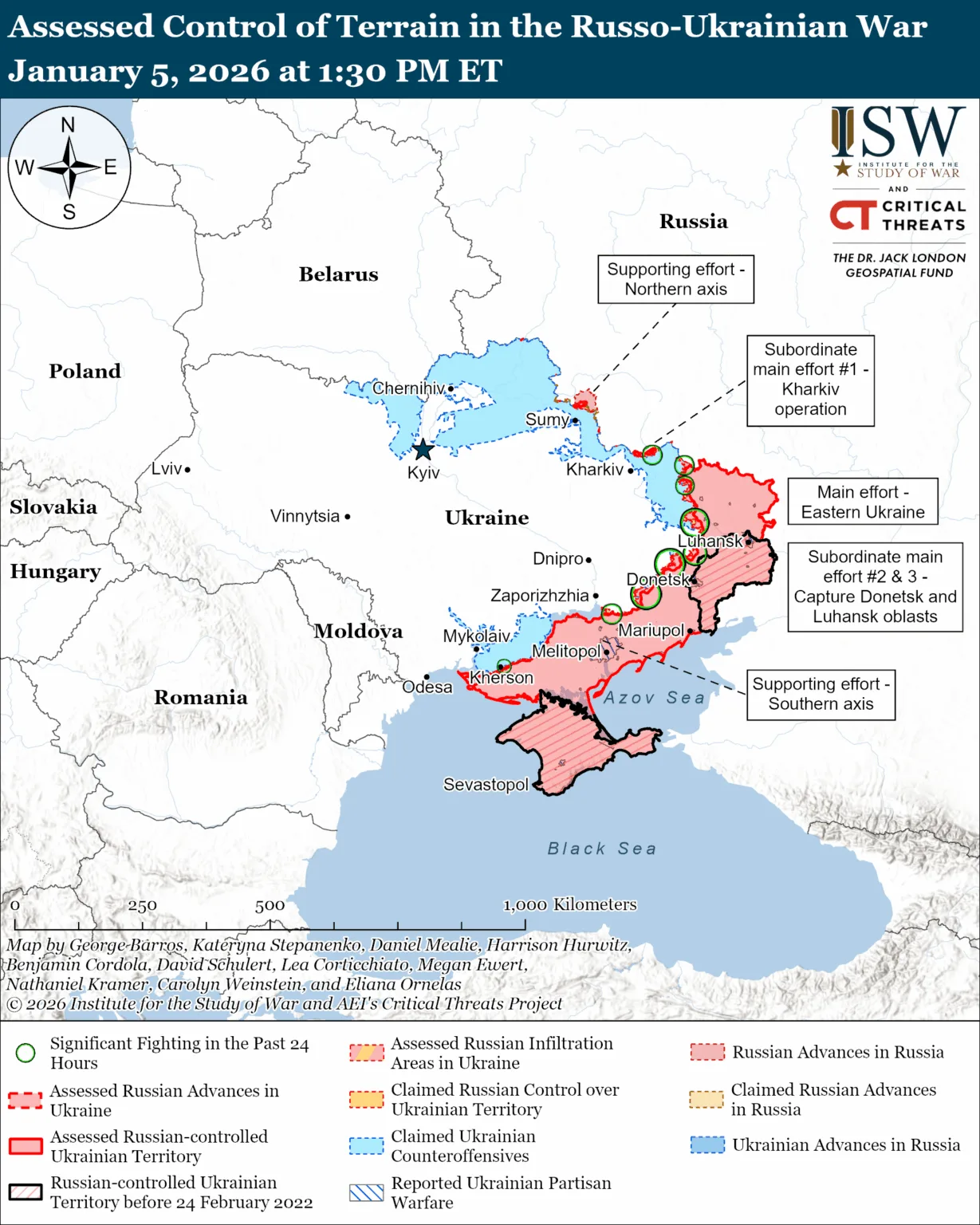

[Russia is gaining the upper hand in the ongoing war of attrition against Ukraine; Institute for the Study of War, via Understanding War Institute.]

Mar-A-Lago and Strategic Myopia

The December 28 meeting between Donald Trump and Volodymyr Zelenskyy at Mar-a-Lago briefly created the impression of diplomatic momentum. In reality, it reinforced a more troubling truth: the Russia–Ukraine war remains structurally resistant to any clearly defined, durable peace. The problem lies less in the absence of dialogue than in the absence of a coherent settlement framework.

Washington’s approach reflects a deeper short-sightedness. Trump treats Ukraine primarily as a transactional negotiation, shaped by personal diplomacy and the promise of quick closure. Implicit in this approach is the belief that post-war economic engagement could soften Russia’s strategic alignment with China. This assumption is deeply flawed.

This strategic ambiguity is not confined to Ukraine. It has been reinforced by recent US actions and rhetoric elsewhere. Washington’s attack on Venezuela and the capture of its president, Nicolás Maduro, and renewed talk from Donald Trump and his advisers about annexing Greenland, have introduced a new and unsettling dimension to global crises. Greenland is part of Denmark—a founding member of NATO. When revisionist language enters mainstream American diplomacy, it normalises coercion elsewhere. It legitimises Russian and Chinese revanchism and weakens the alliances that once enforced restraint. Any military-led move on Greenland would not only damage NATO, but fundamentally strain the transatlantic compact itself.

At the core of the conflict lies a simple but uncomfortable reality: Moscow has not revised its war aims. Any strategy premised on ceasefires, territorial freezes, or interim arrangements assumes a Russian interest in stability. The evidence suggests the opposite. For Vladimir Putin, ambiguity is an asset. Time erodes Ukrainian capacity, strains European unity, and exposes fissures within the transatlantic alliance. A conflict suspended between war and peace serves Russian interests far better than a clearly defined settlement.

Western strategy, by contrast, continues to oscillate between escalation management and rhetorical urgency without articulating how negotiations translate into enforceable security guarantees. A premature or poorly structured peace would not resolve the conflict so much as formalise instability—preserving leverage for Moscow while normalising territorial revisionism achieved through force.

Russia’s war economy has displayed greater resilience than many expected. Defence-linked industrial activity has accounted for nearly all measurable industrial growth since 2022, sustained by expansive state spending, redirected trade flows, and continued energy revenues. Wage growth in military-adjacent sectors has temporarily offset labour shortages caused by mobilisation and emigration.

Yet this apparent robustness conceals deeper fragilities. Inflation remains persistent because wage gains are detached from productivity. Labour shortages are structural rather than cyclical. Innovation has slowed, investment horizons have shortened, and long-term growth potential is being sacrificed for endurance. Russia is not preparing for post-war recovery; it is deferring costs into the future.

These vulnerabilities are compounded by Russia’s deepening dependence on China. What Moscow presents as a strategic partnership increasingly resembles asymmetric reliance.

Russia-China: Dependence Disguised as Partnership

Russia’s isolation from Western capital, technology, and markets has forced a rapid reorientation eastward. Trade, energy exports, and financial flows have been redirected toward China, often on terms that favour Beijing. Discounted commodity sales, yuan-denominated transactions, and reduced bargaining power reflect a shift that preserves regime survival in Moscow but steadily erodes strategic autonomy.

China benefits disproportionately. It secures reliable access to energy and raw materials, advances the internationalisation of the yuan, and strengthens continental supply routes insulated from maritime chokepoints. Just as importantly, it acquires a weakened but functional partner that absorbs Western attention in Europe, allowing Beijing greater strategic room in the Indo-Pacific.

This asymmetry is increasingly visible in diplomatic signalling. Russia’s unequivocal endorsement of China’s position on Taiwan reflects not strategic autonomy, but the logic of a junior partner seeking reassurance from its principal economic anchor. In seeking to escape Western pressure, Moscow has locked itself into a form of dependency that would have been politically unthinkable a decade ago.

Asia-Pacific: Ukraine as a Deterrence Test

The persistence of the Russia–Ukraine war is reshaping strategic calculations across the Asia-Pacific—not through direct military spillover, but through its corrosive effects on deterrence credibility, alliance cohesion, and perceptions of Western resolve. Ukraine has become a live case study in how prolonged conflict, ambiguous diplomacy, and incomplete outcomes alter the balance between coercion and restraint.

For Taiwan, the implications are unsettling. Territorial revisionism has proven capable of persistence despite sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and international condemnation. Beijing is watching not only battlefield outcomes, but the political endurance of Western coalitions and their tolerance for ambiguity. A settlement that rewards partial conquest or leaves sovereignty unresolved would weaken deterrence in the Taiwan Strait by reinforcing the belief that time, military pressure, and persistence can erode red lines.

Japan has responded accordingly. As a frontline US ally acutely sensitive to shifts in regional power balances, Tokyo increasingly views European instability as an Indo-Pacific problem by extension. Rising defence budgets, an emphasis on counter-strike capabilities, and deeper coordination with NATO partners reflect a belief that deterrence must be layered, visible, and multinational.

For South Korea, the lessons are more ambivalent but no less consequential. Seoul faces the dual challenge of managing an unpredictable North Korea while navigating intensifying US–China rivalry. The endurance of the Ukraine conflict highlights how unresolved great-power confrontations can become normalised, increasing long-term instability while reducing urgency for resolution.

Across Southeast Asia, the conclusions are quieter but equally sobering. States operating below the threshold of formal alliance guarantees rely on calibrated balancing, legal mechanisms, and external diplomatic support. The Ukraine war underscores the limits of international law when confronted by sustained coercion and reinforces concerns that external partners may condemn violations yet hesitate to incur prolonged costs to reverse them.

India: The Strategic Costs of Ambiguity

For India, the persistence of the Russia–Ukraine war—and the prospect of an ambiguous or Russia-influenced peace—creates a complex and narrowing set of strategic choices. New Delhi has thus far navigated the conflict with considerable diplomatic dexterity, preserving relations with Moscow while deepening engagement with the United States and Europe. But the longer the war endures without resolution, the more difficult this balancing act becomes.

Discounted Russian energy imports have provided short-term economic relief, but a prolonged war accelerates Russia’s dependence on China, steadily eroding Moscow’s autonomy. For India, this erosion matters. A Russia structurally dependent on Beijing offers far less strategic flexibility in a future crisis.

As India negotiates deeper trade, technology, and defence arrangements with the United States, its room for strategic ambiguity inevitably narrows. If Washington appears willing to accommodate Russian territorial gains in Europe, it weakens the normative foundations of its Indo-Pacific posture and raises questions in NewDelhi about the durability of American commitments under pressure.

An unresolved European war further accelerates global fragmentation. India stands to gain from supply-chain diversification, but only if it can preserve strategic autonomy. Prolonged ambiguity increases uncertainty, raises the costs of hedging, and complicates long-term industrial strategy.

For India, the true cost of this conflict lies not in energy prices alone, but in the steady narrowing of strategic choice in an increasingly fragmented world.

A World Stuck Between War and Peace

The defining feature of the current global order is no longer the frequency of crises, but their durability. Conflicts are not moving toward resolution but settling into extended states of ambiguity—neither fully contained nor decisively concluded. What is emerging is a fragile architecture in which coercion is normalised, deterrence is incrementally tested, and uncertainty becomes institutionalised.

The Russia–Ukraine war sits at the centre of this shift, not because it is the only conflict that matters, but because it has exposed how poorly equipped existing institutions and strategies are to deliver credible endgames. A premature or poorly structured peace would not stabilise the system; it would legitimise revisionism, reward endurance over restraint, and encourage similar behaviour across other theatres. In that sense, ambiguity itself has become a strategic outcome.

The same pattern is visible beyond Europe and the Indo-Pacific. In the Middle East, Iran represents a different but equally consequential fault line. The unrest now unfolding inside the country is the most serious challenge to the Ayatollah–Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps system in decades—not because it is revolutionary in intent, but because it is economic in character, geographically diffuse, and rooted in a fraying social contract. What matters systemically is less the prospect of immediate regime change than the strategic constraints this instability imposes.

Iran’s capacity to project power is increasingly shaped by domestic economic pressure, sanctions fatigue, and fiscal exhaustion. External partnerships offer limited insulation. Russia is preoccupied with its own war economy. China cushions Iran through discounted oil purchases, but remains cautious, transactional, and unwilling to underwrite a weakening regime. In this environment, instability does not resolve; it lingers. A pressured Iran may retrench, miscalculate, or seek external confrontation to offset internal strain—each outcome adding friction to an already stressed global system.

China has adapted most effectively to this environment of prolonged uncertainty, extracting advantage from ambiguity while deepening alignment with a weakened Russia and expanding leverage across Europe and Asia. Europe remains constrained by internal divisions and economic dependencies. The United States oscillates between transactional diplomacy and rhetorical urgency without articulating how short-term deals connect to long-term stability. Middle powers such as India find their room for manoeuvre narrowing as global fragmentation accelerates.

The danger ahead lies not in a single dramatic rupture, but in the steady erosion of constraints on power. In a world where conflicts linger unresolved and red lines blur, the incentives favour persistence, pressure, and incremental coercion. Preventing that outcome requires more than crisis management or ceasefires. It demands strategies that reconnect diplomacy to enforceable outcomes and confront the structural shifts underway rather than masking them with temporary fixes.

Until then, the world risks settling into a prolonged in-between state—neither at war nor at peace, but suspended in a condition of managed instability that quietly reshapes power, erodes norms, and narrows choice.