[Photo by Yeshi Kangrang on Unsplash]

Good morning,

Many sense-making exercises are being attempted right now. One of this includes attempting to predict the caseload the Indian healthcare system must deal with in the days to come. While it is much needed, the tools available to predict the caseloads must be used with caution. It is something that statistician and writer Nate Silver highlights in his book The Signal and the Noise: The Art and Science of Prediction.

“The wide array of statistical methods available to researchers enables them to be no less fanciful—and no more scientific—than a child finding animal patterns in clouds. ‘With four parameters I can fit an elephant,’ the mathematician John von Neumann once said of this problem. ‘And with five I can make him wiggle his trunk.’

“Overfitting represents a double whammy: it makes our model look better on paper but perform worse in the real world. Because of the latter trait, an overfit model eventually will get its comeuppance if and when it is used to make real predictions. Because of the former, it may look superficially more impressive until then, claiming to make very accurate and newsworthy predictions and to represent an advance over previously applied techniques. This may make it easier to get the model published in an academic journal or to sell to a client, crowding out more honest models from the marketplace. But if the model is fitting noise, it has the potential to hurt the science…

“To be clear, these mistakes are usually honest ones. To borrow the title of another book, they play into our tendency to be fooled by randomness. We may even grow quite attached to the idiosyncrasies in our model. We may, without even realizing it, work backward to generate persuasive-sounding theories that rationalize them, and these will often fool our friends and colleagues as well as ourselves. Michael Babyak, who has written extensively on this problem, puts the dilemma this way: ‘In science, we seek to balance curiosity with scepticism.’ This is a case of our curiosity getting the better of us.”

Stay safe and have a good day.

In this issue

- What India must learn from Brazil

- What college to pick?

- Who will survive?

What India must learn from Brazil

In February, when the number of cases in India was falling sharply and many of us thought it might be the beginning of the end of the pandemic, AIIMS director Randeep Guleria pointed to Brazil, warning us not to take it for granted.

“They (Brazil) had claimed that they got herd immunity with almost 70% of the population being protected because of the past infection, and yet because of the Brazilian variant and waning immunity, a large number of people got infected again. And now they are in a very bad situation because of the resurgence of cases,” he noted. (PTI)

Hardly two months later, India is experiencing its worst outbreak—far exceeding its healthcare capacity.

[Pixabay/alefukugava]

Brazil also has lessons for a group of people whom many assume are safe from Covid-19—the young.

Bloomberg reports: “In March, 3,405 Brazilians aged 30 to 39 died from Covid, almost four times the number in January. Among those in their 40s, there were about 7,170 fatalities, up from 1,840, and for those 20-29, deaths jumped to 880 from 245. Those under 59 now account for more than a third of Covid deaths in Brazil, according to research firm Lagom Data. As the elderly get vaccinated, their deaths have fallen by half.

There are many causes for the alarming shift but one appears to be that the young have trouble accepting they are at risk.

“‘Because they’re young and the virus first infected the elderly population, they don’t believe or don’t want to believe that it can be serious,’ said Dr Suzana Morais, a cardiologist in Rio de Janeiro. ‘I’ve seen many young patients who are surprised. Others are aware but take risks.’”

It’s also true that after months of government aid and staying home, the money is running out and people have to work again, exposing them to risk in a society that hasn’t done well at imposing masks and distancing.

The story ends with this sobering quote: “We don’t have a unified message from the government about the real need for social distancing,” said Dr Morais, the Rio cardiologist. “In the end, young people don’t respect this much. You have an economically active population that needs to work and they simply don’t have many options.”

Dig deeper

What college to pick?

One casualty of the pandemic has been that passing-out examinations from schools have been cancelled. It is inevitable then that parents and children routinely speak about how concerned they are about how to pick a college. Conventional wisdom has it that the college you go to matters much in the longer term. But education writer Jay Mathews offers a counter-intuitive perspective in The Washington Post. His research and data crunching has it that reputation, the factor that leads students to apply to the most prestigious places, “was on average at the very bottom of the hiring executives’ priority lists.

[Pixabay]

“(Steve) Becker discusses some of the unappreciated truths that I have focused on, such as the large number of corporate chief executive officers who did not attend Ivy-like schools and the dearth of ultra-selective college grads in competitive jobs. I looked at US senators and TV news anchors. Becker examined astronauts, brain specialists and many other big job categories.

“He also gives great weight, as he should, to a landmark study by Stacy Berg Dale and Alan Krueger showing that students who were admitted to very selective colleges but attended less selective ones, were making just as much money 20 years later as the super-selective college grads. Dale and Krueger concluded that character traits the students acquired long before college, such as persistence, humour and warmth, led to their success, not the college name on their diploma.

“My favourite stress-reducing technique is to remember that if you want something you discover your college doesn’t have, you can transfer to another one. Barack Obama, Donald Trump and I did that.”

Dig deeper

Still curious?

- In his book, Superforecasting, Philip Tetlock looked at those who predict the future right and how they do it. Read: Six people who can help you become a superforecaster, by NS Ramnath

- Indian institutions tend to decay over time. The Indian Institute of Science seems to have defied this trend thanks to a strong commitment to certain core principles, writes Rishikesha T Krishnan. Read: India can build world-class universities. IISc shows how, with a few caveats

- There are things you can do to care at home, at the first signs of an infection, before you get to go to the hospital, writes Haresh Chawla. Read: My tryst with Covid-19

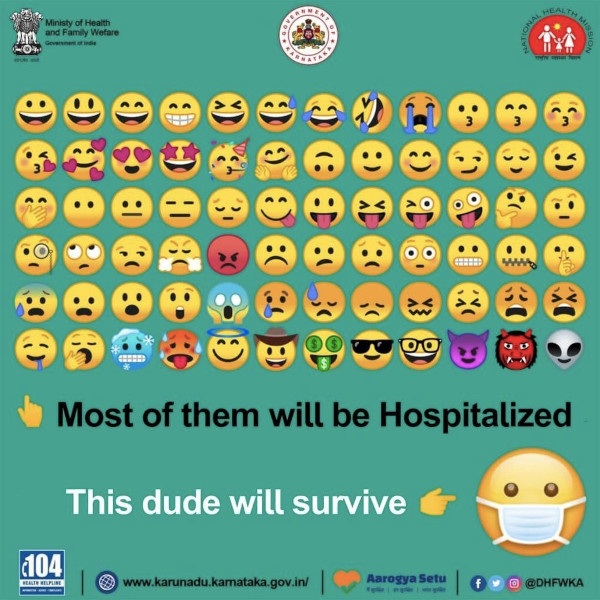

Who will survive?

(Ministry of Health and Family Welfare)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)