A Test match in progress — imagined through AI — capturing the ritual, scale, and sustained attention that define the format at its best.

Test cricket gave us both its magic and its fragility in 2025. As the Ashes once again filled stadiums in Australia — with the Boxing Day Test at the MCG drawing record crowds — the format reminded us of its enduring power when it is framed as an event rather than background noise. That some of these matches ended quickly only underlined the point: even brief contests can command deep attention when anticipation, ritual, and occasion are right. Elsewhere, however, poorly positioned Tests drifted past half-empty stands, reinforcing the sense that the format is losing its place in a crowded attention economy.

The problem isn’t that Test cricket is a bad product.

It’s that it’s being badly positioned.

For 150 years, Test cricket’s first innings built the foundations of the sport’s global brand. Its second innings will require a different way of thinking — about audience, scarcity, place, and value.

Misreading the product

Test cricket has a different audience and purpose from T20s, yet we persist in treating them as variants of the same entertainment product.

T20 cricket is designed to widen engagement: fast, loud, accessible. Test cricket does the opposite. At its best, it deepens engagement. It turns spectators into lifelong advocates. Its natural audience is older, more affluent, more patient — the same audience that sustains Wimbledon, the Masters, or long-form cultural festivals.

India’s demographics now support this audience at scale. There is a large, discerning upper middle class that still loves Test cricket — and risks being alienated by an endless churn of poorly scheduled matches and uneven contests.

Empty Test stadiums in India are not evidence of declining interest. They are evidence of a positioning failure.

Scarcity is not a weakness

Many of Test cricket’s supposed liabilities are, in fact, strengths.

It is scarce. Tours happen once every few years. Rivalries take decades to mature. Matches unfold over days, not minutes. In modern sport, scarcity is power — if handled correctly.

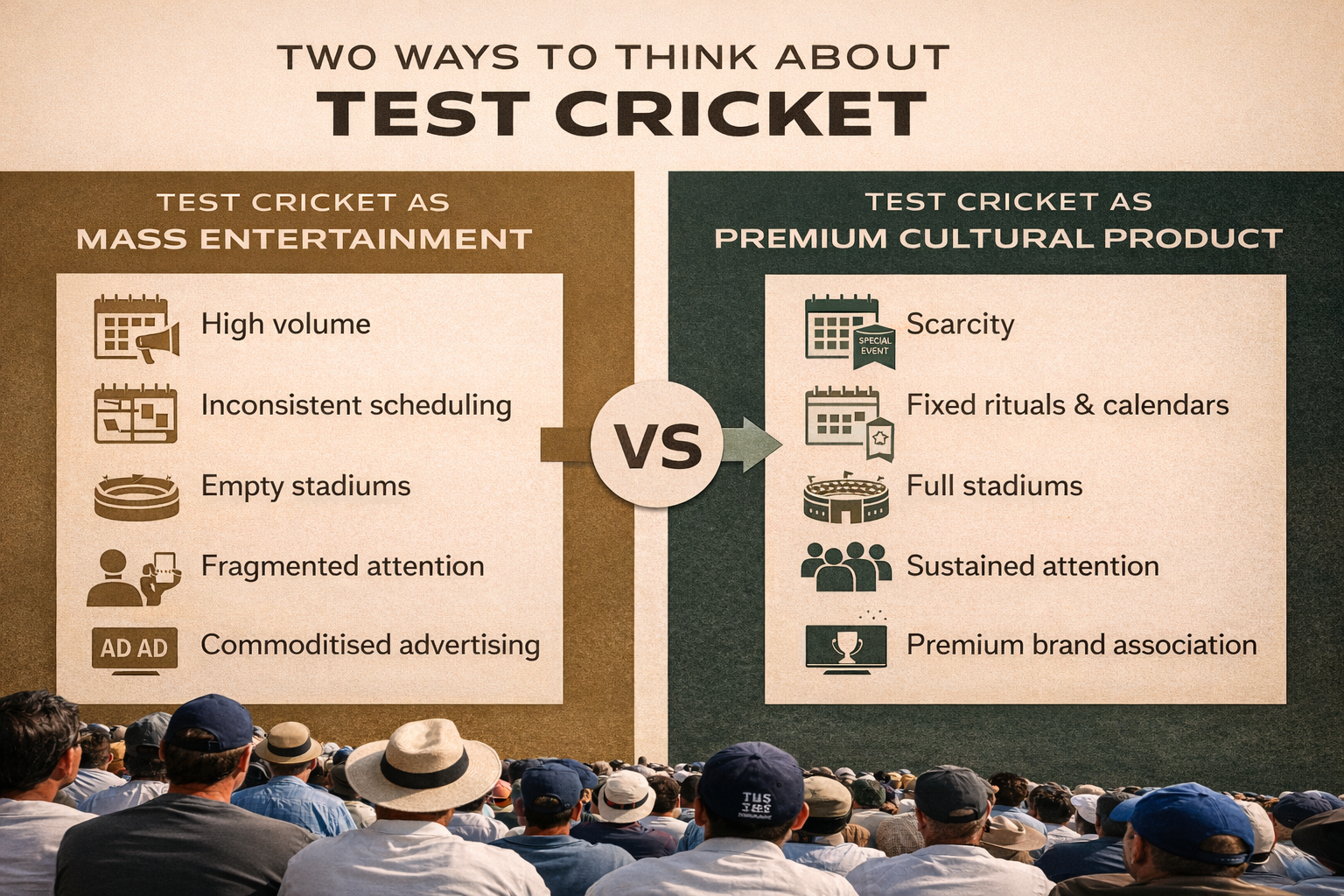

This is also why Test cricket should be thought of less as mass entertainment and more as a premium brand. The world’s most valuable cultural and sporting properties — Wimbledon, the Masters, the NFL — do not chase ubiquity. They protect ritual, scarcity, and tone. Rolex does not advertise everywhere; it advertises where it belongs. Test cricket operates in a similar register. Its value lies not in volume, but in association — with patience, excellence, and tradition. Treated this way, it attracts a different class of audience, sponsor, and attention altogether.

This is a premium advertising environment — but only if the stadiums are full, the contests are credible, and the calendar makes sense.

The NFL plays fewer than 20 games a season, yet commands the world’s richest broadcast deals. The Premier League thrives because every match matters. Test cricket already has this advantage: two nations’ media and fanbases remain engaged for five days at a time, over a four-to-eight-week stretch. Very few sporting products occupy the news cycle that long.

At its heart, this is also a story about attention — the scarcest resource of the modern age. Most contemporary sport is designed to be consumed in fragments: highlights, clips, scrollable moments. Test cricket asks for something different: time, patience, and presence. That demand is often treated as a flaw. In fact, it is the source of its value. In an economy saturated with noise, a product that can hold attention for hours — even days — is not an anachronism. It is a rarity.

India’s leadership moment

Here lies the real leadership question.

Test cricket’s future cannot be solved by the ICC alone. It lacks both the financial muscle and the political authority to enforce long-term thinking. Individual boards, meanwhile, are trapped by incentives that reward short-term gains from franchise T20 cricket over the slower work of sustaining Test cricket.

Only the BCCI sits at the centre of this system with the ability to change those incentives.

Leadership does not mean issuing diktats or underwriting everyone else’s losses.

The BCCI already does this informally — through its control over the calendar, broadcast negotiations, and bilateral series. Exercised deliberately, that influence could reshape the ecosystem: longer, better-spaced Test series; fewer, more meaningful contests; predictable windows that allow fans, broadcasters, and host cities to plan years in advance.

It also means leading by example. If Test cricket in India becomes visibly premium — full stadiums, coherent calendars, strong overseas attendance, and sustained advertiser interest — other boards will follow. Just as the IPL reset expectations around franchise cricket, a reimagined Indian Test season could reset expectations for the format globally.

In the 20th century, Indian cricket was a rule-taker. In the 21st, it became a rule-maker. The next step is stewardship.

Place, ritual, and anticipation

Test cricket works best when it is anchored to place and time.

England’s Test summer aligns with school holidays. The Boxing Day Test belongs to Melbourne. These traditions create anticipation and travel.

India can do the same — and at scale.

That requires turning Tests into fixtures people plan around, not stumble upon.

A Pongal Test in Chennai.

A Republic Day Test every January.

A Bombay Test aligned with the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival.

For overseas fans, Test cricket should become the centrepiece of a once-in-a-lifetime trip. One part of the family goes to the stadium; the other explores the city. Cricket becomes culture, not just content.

Forty thousand English fans travel to Australia for the Ashes. If even a fraction travelled to India, the economic impact would be significant.

Stadiums as civic infrastructure

None of this works without better stadiums.

Too many Indian stadiums remain uncomfortable, under-utilised, and empty for most of the year. That is not a resource problem; it is a failure of imagination.

A modern Test venue should function as a civic space — clean, safe, walkable, with restaurants, health clubs, children’s areas, and conference facilities. Somewhere families are happy to spend an entire day, even if they step away from the cricket.

These are 50-year assets sitting on prime urban land. With private capital and long-term vision, stadiums can become year-round community and tourism hubs — not just occasional match venues.

The economics are not the constraint

This vision sounds expensive, but the money exists.

The BCCI earned close to Rs.10,000 crore last year. Tourism ministries have a stake in international cricket travel. Hospitality groups can operate on-site facilities. Premium advertisers will pay for association with full, atmospheric stadiums — not empty ones.

The constraint is not capital.

It is conviction.

Reframing Test cricket: from volume to value.

A second innings worth playing

Test cricket does not need saving. It needs reframing.

It is the best players in the world, at the highest level, over the longest time — a sporting product unlike any other. Treated as mass entertainment, it will struggle. Treated as a premium cultural experience, it can thrive.

This second innings will require restraint, focus, and institutional confidence. Many of the levers sit with the BCCI. Used wisely, they can ensure that Test cricket remains what it has always been at its best: demanding, elegant, and unforgettable.